Battle of Inchon

MacArthur was the driving force behind the operation, overcoming the strong misgivings of more cautious generals to a risky assault over extremely unfavorable terrain.

[7] From their initial 25 June offensive to fighting in July and early August, the KPA used this tactic to defeat the UN forces they encountered and push southward.

[9][20] Logistic problems wracked the KPA, and shortages of food, weapons, equipment and replacement soldiers proved devastating for their units.

MacArthur felt that he could turn the tide if he made a decisive troop movement behind KPA lines,[35] and preferred Incheon, over Chumunjin-up or Kunsan as the landing site.

MacArthur decided instead to use the US Army's 7th Infantry Division, his last reserve unit in East Asia, to conduct the operation as soon as it could be raised to wartime strength.

[42] He also felt that the KPA, who also thought the conditions of the Incheon channel would make a landing impossible, would be surprised and caught off-guard by the attack.

[42] Chief of Staff of the United States Army General Joseph Lawton Collins, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Forrest Sherman, and United States Air Force (USAF) operations deputy Lieutenant General Idwal H. Edward all flew from Washington, D.C., to Japan to take part in the briefing; Chief of Staff of the United States Air Force General Hoyt Vandenberg did not attend, possibly because he "did not want to legitimize an operation that essentially belong[ed] to the Navy and the Marines."

During the briefing, nine members of the staff of US Navy Admiral James H. Doyle spoke for nearly 90 minutes on every technical and military aspect of the landing.

[47] He said that, because it was so heavily defended, the North Koreans would not expect an attack there, that victory at Incheon would avoid a brutal winter campaign, and that, by invading a northern strong point, UN forces could cut off KPA lines of supply and communication.

On 5 September 1950, aircraft of the USAF's Far East Air Forces began attacks on roads and bridges to isolate Kunsan, typical of the kind of raids expected prior to an invasion there.

On the docks at Pusan, USMC officers briefed their men on an upcoming landing at Kunsan within earshot of many Koreans, and on the night of 12–13 September 1950 the Royal Navy frigate HMS Whitesand Bay landed US Army special operations troops and Royal Marine Commandos on the docks at Kunsan, making sure that North Korean forces noticed their visit.

[51] UN forces conducted a series of drills, tests, and raids elsewhere on the coast of Korea, where conditions were similar to Incheon, before the actual invasion.

[53] Separately on 1 September 1950, UN reconnaissance team (members were from US military intelligence Unit including KLO, CIA) also infiltrated in Yonghung-do (Yeongheung Island) to obtain information on the conditions there.

[62] When the KPA discovered that the agents had landed on the islands near Incheon, they made multiple attacks, including an attempted raid on Yonghung-do with six junks.

[72] The UN forces did not become aware of the presence of mines in North Korean waters until early September 1950, raising fears that this would interfere with the Incheon invasion.

During this time, extensive shelling and bombing, along with anti-tank mines placed on the only bridge, kept the small KPA force from launching a significant counterattack.

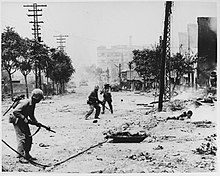

[78] The Red Beach forces, made up of the Regimental Combat Team 5, which included the 3rd Battalion of the Republic of Korea Marine Corps (ROKMC), used ladders to scale the sea walls.

Lieutenant Colonel Raymond L. Murray, serving as commanding officer of the 5th Marines, had the mission of seizing an area 3,000 yards (2,700 m) long and 1,000 yards (910 m) deep, extending from Cemetery Hill (northern) at the top down to the Inner Tidal Basin (near Tidal Basin at the bottom) and including the promontory in the middle called Observatory Hill.

[80] Late on the afternoon of 15 September the LSTs approached Red Beach and as the lead ships, they came under heavy mortar and machine gun fire from KPA defenders on Cemetery Hill.

Their mission, once the beach was secure, was to capture the suburb of Yongdungp'o, cross the Han River, and form the right flank of the attack on Seoul itself.

Seabees and Underwater Demolition Teams (UDTs) that had arrived with the US Marines constructed a pontoon dock on Green Beach and cleared debris from the water.

Early that morning of 16 September, Lieutenant Colonel Murray and Puller had their operational orders from 1st Marine Division commander General Oliver P. Smith.

During the night of 16-17 September, the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines, occupied a forward defensive position commanding the Seoul highway just west of Ascom City.

[83] Just before daylight at 05:50 on 17 September, two Soviet-made North Korean aircraft—probably Yakovlev Yak-9s—were seen overhead from Jamaica, and while trying to identify them any doubts about their allegiance and intentions were resolved by the explosion of a bomb close to the port side of Rochester.

[85] Once it was secured, the Fifth Air Force and USMC aviation units could bring fighters and bombers over from Japan to operate more easily against North Korea.

The Marines repulsed these company-sized counterattacks, inflicting heavy casualties on the KPA troops, who finally fled to the northwest; E Company and supporting tanks played the leading role in these actions.

Continuing its sweep along the river, the 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, on the 19th swung right and captured the last high ground (Hills 118, 80, and 85) a mile west of Yongdungp'o.

Then, from positions on high ground (Hills 208, 107, 178), 3 miles (4.8 km) short of Sosa, a village halfway between Inchon and Yongdungp'o, a regiment of the KPA 18th Division checked the advance.

American forces achieved a strategic masterpiece in the Inchon landing in September 1950 and then largely negated it by a slow, tentative, 11-day advance on Seoul, only 20 miles (32 km) away.

The American advance was characterized by cautious, restrictive orders, concerns about phase lines, limited reconnaissance and command posts well in the rear, while the Germans positioned their leaders as far forward as possible, relied on oral or short written orders, reorganized combat groups to meet immediate circumstances, and engaged in vigorous reconnaissance.

Chinese and

Soviet forces

• South Korean, U.S.,

Commonwealth

and United Nations

forces