Battle of White Sulphur Springs

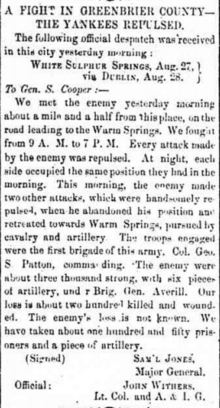

Defending against Averell was a force of four Virginia regiments and an artillery battery at Lewisburg, temporarily commanded by Patton in the absence of Brigadier General John Echols, who was over 200 miles (320 km) away in Richmond.

The Confederate victory proved that Patton could ably command a large force of over 2,000 men, and (unknown to the Confederacy) saved the law library in Lewisburg.

Averell achieved the first two of his three objectives, and his newly-mounted men also gained valuable experience in cavalry tactics in the mountains of West Virginia.

[6] This enabled Confederate Major General William W. Loring to drive Union troops in the Kanawha Valley and Charleston back to the Ohio River.

[16] Brigadier General William W. Averell was a West Point graduate, excellent horseman, and had experience fighting in the New Mexico Territory during the 1850s.

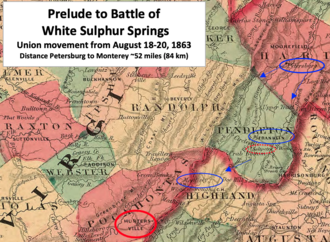

His orders were to go to Huntersville, West Virginia, and drive the Confederate force commanded by Colonel William L. "Mudwall" Jackson out of Pocahontas County.

His force on August 26, en route to White Sulphur Springs, consisted of the 2nd, 3rd, and 8th West Virginia mounted infantry regiments.

[42][Note 7] Further east, Brigadier General John D. Imboden, a native of Staunton, Virginia, commanded the Shenandoah Valley District.

[53] During July 1863, most of Averell's 4th Separate Brigade was involved with small attacks on General Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia as it retreated from the Battle of Gettysburg in Pennsylvania.

A local pro-Union home guard organization that consisted of about 50 men, known as the Swamp Dragons, provided assistance in driving off the Confederate guerrillas.

[23] On the morning of August 19, Averell moved close to Franklin with the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry, 3rd West Virginia Mounted Infantry, and Ewing's Battery.

Averell's wagon train was attacked by Confederate soldiers, and his vanguard drove back about 300 of Mudwall Jackson's men in front of the command.

The next day, Averell sent Gibson's Battalion on what he called a "false advance", while the main portion of his force took a different road and reached Huntersville without any resistance.

During the day, Lieutenant Colonel John J. Polsley led the 8th West Virginia on a reconnaissance mission toward Warm Springs and skirmished with Confederate soldiers.

His advance, consisting of the 26th Virginia Infantry Battalion, reached the junction of Anthony's Creek Road with the James River and Kanawha Turnpike on the morning of August 26 slightly ahead of Averell.

[70] Read's men occupied a house along the road owned by Henry Miller, and they began the battle by firing upon Averell's advance around 9:30 pm.

The vanguard, led by Captain Paul von Köenig of Averell's staff, consisted of two companies each from the 2nd and 8th West Virginia mounted infantries.

A soldier from the 3rd West Virginia wrote that for the next four or five hours, an "almost incessant fire" of artillery and muskets took place as neither side gained the advantage.

At that time, the 2nd West Virginia was caught in an exposed position, so Averell had a portion of the 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry make a mounted charge on the road.

[88] Captain John Bird, the leader of the charging 14th Pennsylvania Cavalry squadron, was wounded, captured, and eventually taken to Libby Prison.

Colonel Browne and the remainder of the regiment joined Harman's force on the small hill, and continued repulsing Union attacks.

When Patton's men came forward the road with their Rebel yell, the battery fired at them and then left on fresh horses moving at a trot.

Colonel William Arnett and the 20th Virginia Cavalry Regiment, from Jackson's command, fired on Averell's rear guard and pursued them on the road to Huntersville.

[107] Despite considerable harassment by guerrillas, Averell's brigade arrived at Marling's Bottom (six miles (9.7 km) northwest of Huntersville) in the evening, where Colonel Thomas Harris and the 10th West Virginia Infantry were posted with Keeper's Battery.

[106] On the next day, Corns arrived north of Huntersville at Marling's Bottom, and discovered he missed Averell's rear guard by two hours.

[102] However, abandoning wounded, night marches, road blockades, and fires left burning to deceive the enemy, are signs of concern about the safety of the brigade.

[102] Confederate Lieutenant Colonel Edgar wrote, "Of all the battles of the Civil War, fought in the Department of Western Virginia, none were more prolonged, more stubbornly fought, more creditable of the commanding officer and his subordinate officers of all arms, or to the rank and file, or more interesting in their details than that of White Sulphur Springs, Dry Creek, or Rocky Gap, as it has been variously called.

"[113][Note 13] A Confederate historian wrote that the "Battle of Dry Creek was one of the hottest, for the numbers engaged, of the war" and "its effect was to turn back Averell's army and preserve for many months a large scope of valuable territory from the devastations of Yankee invasion".

[116] With his Confederate victory, George Patton proved he could handle an independent command of an entire brigade, effectively meeting all attacks and efficiently using his artillery.

[117] His defeat of Averell also meant that Sam Jones could shift his troops to Eastern Tennessee to help counter a threat of a Union army commanded by Major General Ambrose Burnside, who was approaching from the west.