Battle of the Bulge

American resistance on the northern shoulder of the offensive, around Elsenborn Ridge, and in the south, around Bastogne, blocked German access to key roads to the northwest and west which they had counted on for success.

[24] Montgomery and Bradley both pressed for priority delivery of supplies to their respective armies so they could continue their individual lines of advance and maintain pressure on the Germans, while Eisenhower preferred a broad-front strategy.

[35] Hitler's plan called for a Blitzkrieg attack through the weakly defended Ardennes, mirroring the successful German offensive there during the Battle of France in 1940, and aimed at splitting the armies along the U.S.-British lines and capturing Antwerp.

They were given priority for supply and equipment and assigned the shortest route to the primary objective of the offensive, Antwerp,[29] starting from the northernmost point on the intended battlefront, nearest the important road network hub of Monschau.

In an indirect, secondary role, the Fifteenth Army, under General Gustav-Adolf von Zangen, recently brought back up to strength and re-equipped after heavy fighting during Operation Market Garden, was located just north of the Ardennes battlefield and tasked with holding U.S. forces in place, with the possibility of launching its own attack given favorable conditions.

In France, orders had been relayed within the German army using radio messages enciphered by the Enigma machine, and these could be picked up and decrypted by Allied code-breakers headquartered at Bletchley Park, to give the intelligence known as Ultra.

German units assembling in the area were even issued charcoal instead of wood for cooking fires to cut down on smoke and reduce chances of Allied observers deducing a troop buildup was underway.

[49] For these reasons Allied High Command considered the Ardennes a quiet sector, relying on assessments from their intelligence services that the Germans were unable to launch any major offensive operations this late in the war.

After a brief visit to Berlin, Hitler traveled on his Führersonderzug ('Special Train of the Führer') to Giessen on 11 December, taking up residence in the Adlerhorst (eyrie) command complex, co-located with OB West's base at Kransberg Castle.

Von Rundstedt set up his operational headquarters near Limburg, close enough for the generals and Panzer Corps commanders who were to lead the attack to visit Adlerhorst on 11 December, traveling there in an SS-operated bus convoy.

With the castle acting as overflow accommodation, the main party was settled into the Adlerhorst's Haus 2 command bunker, including Gen. Alfred Jodl, Gen. Wilhelm Keitel, Gen. Blumentritt, von Manteuffel and Dietrich.

The Americans' initial impression was that this was the anticipated, localized counterattack resulting from the Allies' recent attack in the Wahlerscheid sector to the north, where the 2nd Division had knocked a sizable dent in the Siegfried Line.

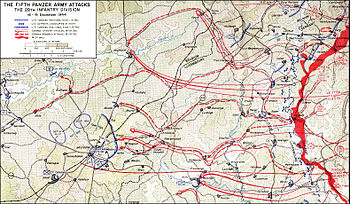

Kampfgruppe Peiper, at the head of Sepp Dietrich's Sixth Panzer Army, had been designated to take the Losheim-Losheimergraben road, a key route through the Losheim Gap, but it was closed by two collapsed overpasses that German engineers failed to repair during the first day.

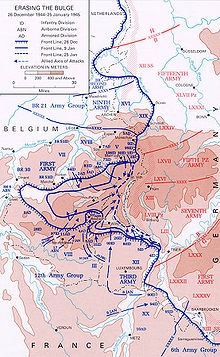

"[88][89] The stiff American defense prevented the Germans from reaching the vast array of supplies near the Belgian cities of Liège and Spa and the road network west of the Elsenborn Ridge leading to the Meuse River.

[90] After more than 10 days of intense battle, they pushed the Americans out of the villages, but were unable to dislodge them from the ridge, where elements of the V Corps of the First U.S. Army prevented the German forces from reaching the road network to their west.

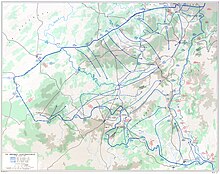

By this time, the town of Bastogne and its network of 11 hard-topped roads leading through the widely forested mountainous terrain with deep river valleys and boggy mud of the Ardennes region was under severe threat.

[citation needed] Gen. Eisenhower, realizing that the Allies could destroy German forces much more easily when they were out in the open and on the offensive than if they were on the defensive, told his generals, "The present situation is to be regarded as one of opportunity for us and not of disaster.

With casualties mounting, and running short on replacements, tanks, ammunition, and supplies, Seventh Army was forced to withdraw to defensive positions on the south bank of the Moder River on 21 January.

Eisenhower wanted Montgomery to go on the counter offensive on 1 January, with the aim of meeting up with Patton's advancing Third Army and cutting off German troops at the tip of the salient, trapping them in a pocket.

Due to the use of landline communications within Germany, motorized runners carrying orders, and draconian threats from Hitler, the timing and mass of the attack was not detected by Ultra codebreakers and achieved complete surprise.

Even Dietrich believed the Ardennes was a poor area for armored warfare and that the inexperienced and badly equipped Volksgrenadier soldiers would clog the roads the tanks needed for their rapid advance.

As the battle ensued, on the northern shoulder of the offensive, Dietrich stopped the armored assault on the twin villages after two days and changed the axis of their advance southward through the hamlet of Domäne Bütgenbach.

Morelock states that Monty was preoccupied with being allowed to lead a "single thrust offensive" to Berlin as the overall commander of Allied ground forces, and that he accordingly treated the Ardennes counteroffensive "as a sideshow, to be finished with the least possible effort and expenditure of resources.

[152][153][154][155] After conducting several interviews via an interpreter, Liddell Hart in a subsequent book attributed to Manteuffel the following statement about Montgomery's contribution to the battle in the Ardennes: The operations of the American 1st Army had developed into a series of individual holding actions.

[159] In contrast, historian Professor John Buckley, writing in 2013, noted how Montgomery "must take considerable credit" for stabilising the position, due to his "efficient and disciplined system of controlling or gripping subordinates".

Dupuy, David Bongard, and Richard Anderson list battle casualties for XXX Corps combat units as 1,462, including 222 killed, 977 wounded, and 263 missing to 16 January 1945 inclusive.

Casualties among American divisions (excluding attached elements, corps and army-level combat support, and rear-area personnel) totaled 62,439 from 16 December 1944 to 16 January 1945, inclusive: 6,238 killed, 32,712 wounded, and 23,399 missing.

The rapid advance by the German forces who surrounded the town, the spectacular resupply operations via parachute and glider, along with the fast action of General Patton's Third U.S. Army, all were featured in newspaper articles and on radio and captured the public's imagination; there were no correspondents in the area of Saint-Vith, Elsenborn, or Monschau-Höfen.

[191] At Bletchley Park, F. L. Lucas and Peter Calvocoressi of Hut 3 were tasked by General Nye (as part of the enquiry set up by the Chiefs of Staff) with writing a report on the lessons to be learned from the handling of pre-battle Ultra.

[202] It sets out the various indications of an impending offensive that were received, then offers conclusions about the wisdom conferred by hindsight; the dangers of becoming wedded to a fixed view of the enemy's likely intentions; over-reliance on "Source" (i.e. ULTRA); and improvements in German security.