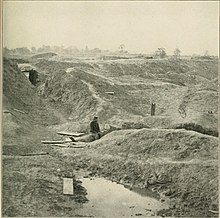

Battle of the Crater

Elements of the Army of Northern Virginia The Battle of the Crater took place during the American Civil War, part of the Siege of Petersburg.

The breach was sealed off, and the Union forces were repulsed with severe casualties, while Brigadier General Edward Ferrero's division of black soldiers was badly mauled.

Burnside was relieved of command for his role in the fiasco, and he was never returned to command,[1] while Ferrero and General James H. Ledlie were observed behind the lines in a bunker, drinking liquor throughout the battle: Ledlie was criticized by a court of inquiry into his conduct that September, and in December he was effectively dismissed from the Army by Meade on orders from Grant, formally resigning his commission on January 23, 1865.

Finally, Lt. Col. Henry Pleasants, commanding the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry of Major General Ambrose E. Burnside's IX Corps, offered a novel proposal to break the impasse.

Digging began in late June, but even Grant and Meade saw the operation as a "mere way to keep the men occupied" and doubted it of any actual tactical value.

Earth was removed by hand and packed into improvised sledges made from cracker boxes fitted with handles, and the floor, wall, and ceiling of the mine were shored up with timbers from an abandoned wood mill and even from tearing down an old bridge.

The shaft was elevated as it moved toward the Confederate lines to make sure moisture did not clog up the mine, and fresh air was drawn in by an ingenious air-exchange mechanism near the entrance.

The fire heated stale air inside of the tunnel, drawing it up the exhaust shaft and out of the mine by the chimney effect.

The resulting vacuum then sucked fresh air in from the mine entrance via the wooden duct, which carried it down the length of the tunnel to the place in which the miners were working.

However, General John Pegram, whose batteries would be above the explosion, took the threat seriously enough to build a new line of trenches and artillery points behind his position as a precaution.

[8] Pleasants became aware of the Confederate's counter-movements and was able to frustrate their effort by changing the direction of the main and lateral galleries while increasing their depth below the surface.

Grant and Meade suddenly decided to use the mine three days after it was completed after a failed attack known later as the First Battle of Deep Bottom.

[10][7] Burnside had trained a division of United States Colored Troops (USCT) under Brigadier General Edward Ferrero to lead the assault.

[11] Despite the careful planning and intensive training, on the day before the attack, Meade, who lacked confidence in the operation, ordered Burnside not to use the black troops in the lead assault.

Meade may have also ordered the change of plans because he lacked confidence in the black soldiers' abilities in combat and feared that if they were butchered, Radical Republicans would make an issue out of it and claim they were deliberately allowed to be killed.

Brigadier General James H. Ledlie's 1st Division was selected, but he failed to brief the men on what was expected of them and was reported during the battle to be drunk, well behind the lines, and not providing leadership.

Worse than that, Ledlie was known as a coward; during the battle on June 18 he had hidden behind the lines and although his officers and enlisted men knew it, this escaped Burnside's notice.

After more and more time passed and no explosion occurred (the impending dawn creating a threat to the men at the staging points, who were in view of the Confederate lines), two volunteers from the 48th Regiment (Lt. Jacob Douty and Sgt.

[18] Once they had wandered to the crater, instead of moving around it, as the USCT troops had been trained, they thought that it would make an excellent rifle pit in which to take cover.

Soldiers who were not killed outright by the Confederates dropped by the dozens from dehydration and heat stroke, worsened by the frantic mob of men jammed into a small area.

Following the Crater affair a Reb wrote his homefolk that all the colored prisoners "would have been killed had it not been for gen Mahone who beg our men to Spare them."

Disproportionate Union losses were suffered by Ferrero's division of the United States Colored Troops,[3] many of whom were summarily executed on the battlefield or in the rear.

Grant subsequently gave in his evidence before the Committee on the Conduct of the War: General Burnside wanted to put his colored division in front, and I believe if he had done so it would have been a success.

General Meade said that if we put the colored troops in front (we had only one division) and it should prove a failure, it would then be said and very properly, that we were shoving these people ahead to get killed because we did not care anything about them.