Battle of the Plains of Abraham

However, the French failed to take the city and in 1763, following defeat in the Montreal campaign, France ceded most of its possessions in eastern North America to Great Britain in the Treaty of Paris.

The decisive success of the British forces on the Plains of Abraham and the subsequent capture of Quebec became part of what was known in Great Britain as the "Annus Mirabilis" of 1759.

As the Seven Years' War entered its later stages through 1758 and 1759, French forces and colonies in northeastern North America came under renewed attack from British armies.

In 1758 after their defeat in July at the Battle of Carillon, the British took Louisbourg in August, causing Atlantic Canada to fall into their hands, and opening the sea route to attack Quebec.

In preparation for the fleet's approach to Quebec, James Cook surveyed a large portion of the river, including a dangerous channel known as The Traverse.

[13] Wolfe, on surveying the town of Beauport, found that the houses there had been barricaded and organized to allow for musket fire from within; they were built in an unbroken line along the road, providing a formidable barrier.

Members of the Louisbourg Grenadiers, who reached the beach, attempted a generally undisciplined charge on the French positions, but came under heavy fire; a thunderstorm ended the fight and allowed Wolfe to pull his troops back after taking some 450 casualties to Montcalm's 60.

[18] However, the attacks did reduce the number of suppliers available to the French, especially as the British navy, unable to control the St. Lawrence entirely, was successful in blockading the ports in France.

[20] With many men in camp hospitals, British fighting numbers were thinned, and Wolfe personally felt that a new attack was needed by the end of September, or Britain's opportunity would be lost.

Montcalm also expressed frustration over the long siege, relating that he and his troops slept clothed and booted, and his horse was always saddled in preparation for an attack.

It is not known why Wolfe selected Foulon, as the original landing site was to be further up the river, in a position where the British would be able to develop a foothold and strike at Bougainville's force to draw Montcalm out of Quebec and onto the plains.

[27] In his final letter, dated HMS Sutherland, 8:30 p.m. 12 September, Wolfe wrote: I had the honour to inform you today that it is my duty to attack the French army.

Even if the first landing party succeeded in their mission and the army was able to follow, such a deployment would still leave his forces inside the French line of defence with no immediate retreat but the river.

A camp of approximately 100 militia led by Captain Louis Du Pont Duchambon de Vergor, who had unsuccessfully faced the British four years previously at Fort Beauséjour, had been assigned to watch the narrow road at L'Anse-au-Foulon which followed a streambank, the Coulée Saint-Denis.

[17] Vaudreuil and others had expressed their concern at the possibility of L'Anse-au-Foulon being vulnerable, but Montcalm dismissed them, saying 100 men would hold off the army until daylight, remarking, "It is not to be supposed that the enemies have wings so that they can in the same night cross the river, disembark, climb the obstructed acclivity, and scale the walls, for which last operation they would have to carry ladders.

"[34] Sentries did detect boats moving along the river that morning, but they were expecting a French supply convoy to pass that night—a plan that had been changed without Vergor being notified.

A group of 24 volunteers led by Colonel William Howe with fixed bayonets were sent to clear the picket along the road, and climbed the slope, a manoeuvre that allowed them to come up behind Vergor's camp and capture it quickly.

[39] Saunders had staged a diversionary action off Montmorency, firing on the shore emplacements through the night and loading boats with troops, many of them taken from field hospitals; this preoccupied Montcalm.

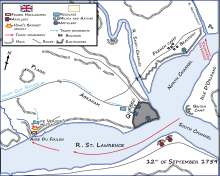

[45] Of the British troops, approximately 3,300 formed into a shallow horseshoe formation that stretched across the width of the Plains, the main firing line being roughly one kilometre long.

On the left wing, regiments under Townshend exchanged fire with the militia in the scrub and captured a small collection of houses and gristmill to anchor the line.

At approximately 10 a.m., Montcalm, riding his dark horse and waving his sword to encourage his men,[48] ordered a general advance on the British line.

Such actions required a disciplined soldiery, painstakingly drilled for as long as 18 months on the parade ground, trained to march in time, change formation at a word, and retain cohesion in the face of bayonet charges and musket volleys.

[51] Captain John Knox, serving with the 43rd Foot, wrote in his journal that as the French came within range, the regiments "gave them, with great calmness, as remarkable a close and heavy discharge as I ever saw".

[52] Wolfe, positioned with the 28th Foot and the Louisbourg Grenadiers, had moved to a rise to observe the battle; he had been struck in the wrist early in the fight, but had wrapped the injury and continued on.

Volunteer James Henderson, with the Louisbourg Grenadiers, had been tasked with holding the hill, and reported afterwards that within moments of the command to fire, Wolfe was struck with two shots, one low in the stomach and the second, a mortal wound in the chest.

The 78th Fraser Highlanders were ordered by Brigadier-General James Murray to pursue the French with their swords, but were met near the city by a heavy fire from a floating battery covering the bridge over the St. Charles River as well as militia that remained in the trees.

When the highlanders were gathered together, they lay'd on a separate attack against a large body of Canadians on our flank that were posted in a small village and a Bush of woods.

[58] During the retreat, Montcalm, still mounted, was struck by either canister shot from the British artillery or repeated musket fire, suffering injuries to the lower abdomen and thigh.

On 28 April, Lévis' forces met and defeated the British at the Battle of Sainte-Foy, immediately west of the city (near the site of Université Laval today).

The Treaty of Paris was signed in 1763 to end the war and gave possession of parts of New France to Great Britain, including Canada and the eastern half of French Louisiana—lying between the Mississippi River and the Appalachian Mountains.