Battle of the Yarmuk

[12] The Muslim invasion of Syria was a series of carefully planned and well-co-ordinated military operations, which employed strategy, instead of pure strength, to deal with the Byzantine defensive measures.

Having secured southern Palestine, Muslim forces now advanced up the trade route, and Tiberias and Baalbek fell without much struggle and conquered Emesa early in 636.

[20] The assembled Byzantine army contingents consisted of Slavs, Franks, Georgians, Armenians, Christian Arabs, Lombards, Avars, Khazars, Balkans and Göktürks.

He did not wish to engage in a single pitched battle but rather to employ central position and fight the enemy in detail by concentrating large forces against each of the Muslim corps before they could consolidate their troops.

Alert to the possibility of being caught with separated forces that could be destroyed, Khalid called a council of war and advised Abu Ubaidah to pull the troops back from Palestine and Northern and Central Syria and concentrate the entire Rashidun army in one place.

[28][29] Abu Ubaidah ordered the concentration of troops in the vast plain near Jabiyah, as control of the area made cavalry charges possible and facilitated the arrival of reinforcements from Umar, so that a strong, united force could be fielded against the Byzantine armies.

[33] The battlefield lies in the plain of Jordanian Hauran, just southeast of the Golan Heights, an upland region currently on the frontier between Jordan and Syria, east of the Sea of Galilee.

Strategically, there was only one prominence in the battlefield: a 100 m (330 ft) elevation known as Tel al Jumm'a, and for the Muslim troops concentrated there, the hill gave a good view of the plain of Yarmuk.

The ravine on the west of the battlefield was accessible at a few places in 636 AD, and had one main crossing: a Roman bridge (Jisr-ur-Ruqqad) near Ain Dhakar[34][35] Logistically, the Yarmuk plain had enough water supplies and pastures to sustain both armies.

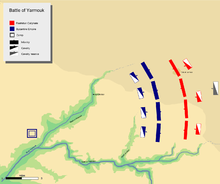

[42] The army was lined up on a front of 12 kilometres (7.5 mi), facing west, with its left flank lying south on the Yarmuk River a mile before the ravines of Wadi al-Allan began.

The army's right flank was on the Jabiyah road in the north across the heights of Tel al Jumm'a,[43] with substantial gaps between the divisions so that their frontage would match that of the Byzantine battle line at 13 kilometres (8.1 mi).

[47] A few days after the Muslims encamped at the Yarmuk plain, the Byzantine army, preceded by the lightly armed Ghassanids of Jabalah, moved forward and established strongly fortified camps just north of the Wadi-ur-Ruqqad.

Vahan deployed the Imperial Army facing east, with a front about 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) long,[34] as he was trying to cover the whole area between the Yarmuk gorge in the south and the Roman road to Egypt in the north, and substantial gaps had been left between the Byzantine divisions.

[34] On the other hand, Umar, whose forces at Qadisiyah were threatened with confronting the Sassanid armies, ordered Sa'd ibn Abi Waqqas to enter negotiations with the Persians and to send emissaries to Yazdegerd III and his commander Rostam Farrokhzād, apparently inviting them to Islam.

[62] Phase 1: On 16 August, Vahan decided in a council of war to launch his attack just before dawn, to catch the Muslim force unprepared as they conducted their morning prayers.

The three-pronged attack forced the Byzantine left wing to abandon the Muslim positions they had gained on, and Amr regained his lost ground and started reorganizing his corps for another round.

Despite stiff resistance, the warriors of Yazid on the left flank finally fell back to their camps and for a moment Vahan's plan appeared to be succeeding.

Khalid detached one regiment under Dharar ibn al-Azwar and ordered him to attack the front of the army of Dairjan (left centre) to create a diversion and threaten the withdrawal of the Byzantine right wing from its advanced position.

The death of Dairjan and the failure of Vahan's battle plan left the larger Imperial army relatively demoralized, but Khalid's successful counterattacks emboldened his troops despite their being smaller in number.

[69] On 17 August, Vahan pondered over his failures and mistakes of the previous day, where he launched attacks against respective Muslim flanks, but after initial success, his men were pushed back.

Ikrimah covered the retreat of the Muslims with his 400 members of the cavalry by attacking the Byzantine front, and the other armies reorganized themselves to counterattack and regain their lost positions.

[73] During the four-day offence of Vahan, his troops had failed to achieve any breakthrough and had suffered heavy casualties, especially during the mobile guard's flanking counterattacks.

[75] Until now, the Muslim army had adopted a largely defensive strategy, but knowing that the Byzantines were apparently no longer eager for battle, Khalid now decided to take the offensive and reorganized his troops accordingly.

Byzantine Armenia fell to the Muslims in 638–39, and Heraclius created a buffer zone in central Anatolia by ordering all the forts east of Tarsus to be evacuated.

[48] Khalid knew all along that he was up against a force superior in numbers and, until the last day of the battle, conducted an essentially defensive campaign, suited to his relatively limited resources.

When he decided to take the offensive and attack on the final day of battle, he did so with a degree of imagination, foresight and courage that none of the Byzantine commanders managed to display.

Although he commanded a smaller force and needed all the men he could muster, he had the confidence and foresight to dispatch a cavalry regiment the night before his assault to seal off a critical path of the retreat that he had anticipated for the enemy army.

[94] The original strategy of Heraclius, to destroy the Muslim troops in Syria, needed a rapid and quick deployment, but the commanders on the ground never displayed those qualities.

That stands in stark contrast to the very successful offensive plan, which Khalid carried out on the final day by reorganising virtually all his cavalry and committing it to a grand maneuver, which won the battle.

Vahan is most likely to be his name as it is of Armenian origin ^ i: During the reign of Abu Bakr, Khalid ibn Walid remained the Commander-in-Chief of the army in Syria but at Umar's accession as Caliph he dismissed him from command.