Bayt Nattif

This page is subject to the extended confirmed restriction related to the Arab-Israeli conflict.Bayt Nattif or Beit Nattif (Arabic: بيت نتّيف, Hebrew: בית נטיף and בית נתיף alternatively) was a Palestinian Arab village, located some 20 kilometers (straight line distance) southwest of Jerusalem, midway on the ancient Roman road between Beit Guvrin and Jerusalem, and 21 km northwest of Hebron.

[4] The village was on a hilltop, surrounded by olive groves and almonds, with woodlands of oak and carobs overlooking Wadi es-Sunt (the Elah Valley) to its south.

[10][11] This region was called Idumea on account of it being inhabited largely by the descendants of Esau (Edom) who were converted to Judaism during the time of John Hyrcanus.

Generals were at that time appointed for Idumea, namely, over the entire region immediately south and south-west of Jerusalem, and which incorporated within it the towns of Bethletephon, Betaris [sic] (corrected to read Begabris),[13] Kefar Tobah, Adurim, and Maresha.

[14][15] Based on the writings of Josephus and archaeological discoveries, the town and surrounding region were predominantly Jewish until the Bar-Kokhba revolt of 132–135 CE.

[11] In 1596, Bayt Nattif was listed among villages belonging to the nahiya Quds, in the administrative district Liwā` of Jerusalem, in a tax ledger of the "countries of Syria" (wilāyat aš-Šām) and which lands were then under Ottoman rule.

Above the entrance of the al-Medhafeh was a large block for lintel, featuring elegant mouldings, Guérin assumed it came from an ancient destroyed monument.

[30] In 1883, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine described Bayt Nattif as being "a village of fair size, standing high on a flat-topped ridge between two broad valleys.

In 1928, as a measure of reform, the Mandate Government of Palestine began to apply an Ordinance for the "Commutation of Tithes," this tax in effect being a fixed aggregate amount paid annually.

[56][57] Today, the land whereon was once built Bayt Nattif comprises what is now called The Forest of the Thirty-Five (Hebrew: יַעֲר הַל"ה, romanized: Ya'ar HaLamed He) and is maintained by the Jewish National Fund.

In response, the Jewish National Fund expressed its respect for the actions of Ader’s parents, stating that the monument was legally constructed on state-owned lands.

A search of the interior revealed "a total of 36 kokhim" hewn in two storeys on three walls of the main burial chamber, a room measuring 4 x 5 meters.

[11] Sometime around the beginning of the first millennium, it was converted into a burial chamber and used by the Jewish inhabitants of the town, who carved twelve kokhim and three arcosolia into the walls of the former cistern.

[65][16] Based on the discovery of unused oil lamps and stone-made casting moulds, it is believed that during the late Roman and Byzantine periods the village manufactured pottery, possibly selling its wares in Jerusalem and Eleutheropolis.

[68][16] The discoveries gave rise to a discussion concerning the ethno-religious identity of the potters and, even more interesting, of the customers to which the oil lamps and figurines were sold.

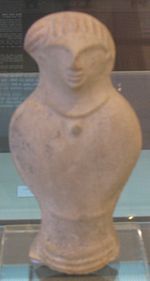

[16] The 1934 findings from the two cisterns included 341 figurines, the main types depicting either nude females or horsemen, possibly used for apotropaic or magical purposes.

[16] Less than 1% of the 600 lamps found in 2014 were decorated with a menorah, widely weakening, along with other considerations, the case for a Jewish identity of the Beit Nattif potters.

[16] Due to the still very meager Late Roman findings from the region, researchers can neither reject nor prove if and which figurines and lamps were produced specifically for pagans or Jews, Lichtenberger concluding that after the Bar-Kokhba revolt, the remaining Jewish population was integrated into a "milieu of cultural pluralism".

[16] Rosenthal-Heginbottom agrees with Jodi Magness that some Beit Nattif lamps were manufactured for Jewish customers, while others were produced with pagan and Christian buyers in mind.

[73] The location of the cisterns excavated by Baramki in 1934 was lost to the next generations, only to be rediscovered in 2020, hidden under the remains of an ornate Early Muslim period building that collapsed in one of a series of 11th century earthquakes, possibly in 1033.