Becky Sharp

Finding herself in Brussels during the Waterloo campaign, as the mistress of a British general, she in no way shares in the alarm felt by other Britons; to the contrary, she soberly makes a contingency plan—should the French win, she would strive to attach herself to one of Napoleon's marshals.

Sharp has been portrayed on stage and in films and television many times, and has been the subject of much scholarly debate on issues ranging from 19th-century social history, Victorian fashions, female psychology and gendered fiction.

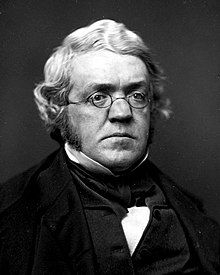

[9][4] According to 19th-century literary norms, the book's heroine should have been the upper-class Amelia Sedley; Thackeray, though, ensures that she is outshone by the lower-class Becky Sharp throughout.

"[3] The story is framed as a puppet show taking place at an 1814 London fair and is narrated by a highly unreliable master of ceremonies who repeats gossip at second or third hand.

Vanity Fair tells the story of Rebecca ("Becky") Sharp, the orphaned daughter of an English art teacher and a French dancer.

After leaving school, Becky stays with Amelia ("Emmy") Sedley, the good-natured and ingenuous daughter of a wealthy London family.

At the Duchess of Richmond's ball in Brussels, Becky embarrasses Amelia by making snide remarks about the quality of the latter's frock; meanwhile, the army receives marching orders to Waterloo.

Becky also has a son, to whom she is cold and distant, being far more interested in first Paris and then London society where she meets the wealthy Marquis of Steyne, by whom she is eventually presented at court to the Prince Regent.

[14] Sharp "manages to cheat, steal and lie without getting caught by the agents of social, moral and economic order who pursue her",[4] which she does by creating for herself a new set of circumstances each time.

Jennifer Hedgecock has commented that:[16] Becky's reputation inevitably catches up to her in each new setting and circle of aristocratic friends, yet her sense of humour and carefree attitude allow her to proceed with new plans.

[16] Born in Soho, Becky Sharp is the daughter of an impoverished English artist and a French "opera girl" — possibly a prostitute[17] — and is thus half-French herself.

[25] Sharp is, says Harold Bloom, "famously a bad woman, selfish and endlessly designing, rarely bothered by a concern for truth, morals, or the good of the community.

Sharp's selfishness is even more highlighted when her husband is preparing to leave on the Waterloo campaign; she is more concerned that he has protected her income in case he is killed than over the risk to his life.

[28] "Her financial gains are always achieved through the exploitation of the affections of others", wrote Ulrich Knoepflmacher; Sharp understood, very early on, that sentiment is a profitable commodity and one to be used and disposed of when circumstances demanded it.

[15] When she first meets Mr Sedley, she tells him her story, of her penniless orphanhood and he gives her gifts;[39] the only character who ever sees through her now well-to-do English facade is Dobbin, who says to himself, "what a humbug that woman is!

[22] The ball is a perfect opportunity for Sharp to dress up in her finest, offset against the glamour of a military campaign and the presence of an entire officer corp.

[43] She makes her sitting room a salon — with "ice and coffee ... the best there is in London — where she can be surrounded by admirers, among whom she ranks men of a "small but elite crowd".

[52] Sharp's fate is, to some degree ambiguous, and it is possible that Thackeray pastiches the classic Victorian novel's denouement in which the heroine makes a "death-in-life renunciation of worldly pleasures"[53]—or the guise of one.

Becky has been married and unmarried; she has risen above the Sedley's social scale only to fall beneath Jos again...She has seen King George, been Lord Steyne's friend, lost Rawdon, left her son, gone to Paris, and lived in a Bohemian garret, accosted by two German students.

Thackeray took a degree of risk in presenting a character such as Sharp, says Michael Schmidt, but he remained within boundaries, and whilst he was satirical, he broke no taboos.

[61] In a modern sense what made her dangerous to contemporary eyes was her ambition; women did not, in nineteenth-century England, climb the social ladder—at least, not in an obvious manner.

[63] Another plot device favoured by Victorian writers was that of children playing adult roles in society, and vice versa,[note 7] and Sharp's comment that she had not been a girl since she was eight years' old has led to her being identified as one such "child-woman".

[67] Henkle suggests that Sharp, with her carefree and radical approach to social barriers, is symbolic of the change that Victorian society was undergoing in the mid-19th century.

[74] Commentator Heather L. Braun describes Becky at the end of the novel as akin to a Rhine maiden, a Clytemnestra: "she has become 'an apparition' that 'glides' rather than walks into a room; her hair 'floats' around her pale face, framing a 'ghastly expression' that elicits fear and trembling in those who look upon her".

[84] In 1848, writing in The Spectator, R. S. Rintoul wrote Rebecca Crawley (formerly Sharp) is the principal person in the book, with whom nearly all the others are connected: and a very wonderfully drawn picture she is, as a woman scheming for self-advancement, without either heart or principle, yet with a constitutional vivacity and a readiness to please, that saves her from the contempt or disgust she deserves.

[88] In an unpublished 1911 essay, novelist Charles Reade used the accepted image of Sharp to illustrate Madame du Barry's assertion that the most foolish woman can trick a man, by using against him the education that he has paid for.

[89] It has in turn been suggested that du Barry was a direct model for Thackeray's Sharp, with both women being "careless beauties cursed with ambition beyond reason, who venture into activities beyond morals".

[90] Another possible model for Sharp from the same era suggested Andrew Lang, maybe Jeanne de Valois, notorious for her involvement in the affair of the Diamond Necklace.

[68] Other possible models for the Sharp character have been suggested as Mary Anne Clarke and Harriette Wilson, two of the most well known English courtesans of the Regency era.

[104] Andrew Davies wrote the screenplay of a BBC television drama of Vanity Fair which was screened in 1998; Natasha Little played Becky Sharp.