Bed hangings

Bed hangings were made of various fabrics, depending on the place, time period, and wealth of the owner.

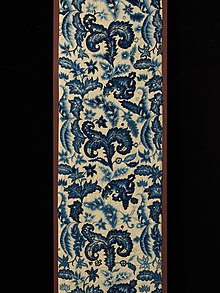

Hangings from the UK used floral, leaf, chinoiserie, and animal themes at various times, and those from the American Colonies often followed suit, though with less dense stitching to preserve scarce crewel wool.

[2] Given the public locations of some beds, the decorated hangings also served as a show of wealth[3] and helped to keep warmth in.

Although many examples of crewel work survive, such curtains are rarely specified in inventories, and wealthier owners paid for embroidery in coloured silks and gold and silver thread.

[20] Bess of Hardwick owned an opulent "Pearl bed" featuring the Cavendish heraldry, which she bequeathed to her daughter, the Countess of Shrewsbury.

The valences were of black velvet embroidered with pearls and silver "sivines and woodbines" (wild raspberries and vines).

"Passamayne", a variety of bobbin woven lace was made of silver and gold Venice thread to trim the beds of Henry VIII and James V of Scotland.

[27] The curtains of a bed owned by Anne of Denmark in the first decade of the 17th century were made of fabric in panes of alternating colour, the seams covered with lace of green silk with gold and silver thread.

[28] Aristocrats like Elizabeth Preston, Countess of Desmond of Kilkenny Castle, bought stocks of gold and silver thread for passementerie, which may have been made up to their specification by specialist weavers.

Elaborately decorated bed hangings were known in medieval and renaissance France as courtepointerie, a term now associated with quilts.

Although better known for their tapestries, there and at Versailles, professional embroiderers worked on royal commissions of bed hangings based on the designs of painters.

[31] Professional workers embroidered padded gold threads on velvet or satin, used braid-outlined appliqué, sometimes with silk embroidery for use as furnishings such as valences.

As part of her trousseau, she brought a four poster marriage bed with 23 hangings attached to the canopy.

[39] Robynet had a team of four men and three female embroiderers who were paid wages and board money to lodge in Richmond Palace for seven weeks.

The account mentions black crewel wool used to "purfulle" or purfle around the roses, and tawny thread used to lay embroidered work on red satin edges.

Regardless, the work involved a great deal of time and effort, as it required decorating large expanses of fabric.

[49] According to Hedlund, it is possible that few pieces of 17th century crewel bed hangings survive because women did not have the leisure time to work on them.

Few full sets of bed hangings were passed down intact, because their worth often meant they were divided amongst surviving heirs.

Later in the Colonial period some sets of hangings were smaller, including only side curtains at the head of the bed and valances.

[52] In Great Britain, an embroidered valance made for Colin Campbell of Glenorchy and Katherine Ruthven including their initials and depicting Adam and Eve, is now at the Burrell Collection in Glasgow.

[55] In 1597 the German traveller Paul Hentzner was shown a tester at Hampton Court which Anne Boleyn had embroidered as a gift for Henry VIII, this is not known to have survived.

[56][57] The Burrell Collection has a cream silk taffeta valance decorated with black velvet cutwork including the initials of Henry and Anne Boleyn, and their emblems of acorns and honeysuckle.

[60] A silk fabric-hung bed for Mary of Guise in a style of 1540 was recreated from inventory evidence in 2010 for display at Stirling Castle.

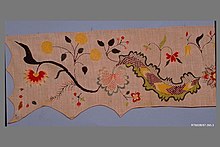

[61] In the United States, the only complete set of embroidered bed hangings are those made by Mary Bulman, most likely in the 1730s, which are housed in the Old Gaol Museum in York, Maine.

[65] The Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam has an almost complete set of 18th-century Chinese silk embroidered bed hangings, missing only the tester and the headboard.