Chinoiserie

'China style') is the European interpretation and imitation of Chinese and other Sinosphere artistic traditions, especially in the decorative arts, garden design, architecture, literature, theatre, and music.

It is related to the broader current of Orientalism, which studied Far East cultures from a historical, philological, anthropological, philosophical, and religious point of view.

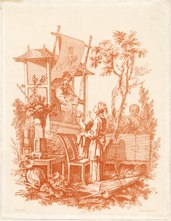

The popularity of chinoiserie peaked around the middle of the 18th century when it was associated with the Rococo style and with works by François Boucher, Thomas Chippendale, and Jean-Baptist Pillement.

It was also popularized by the influx of Chinese and Indian goods brought annually to Europe aboard English, Dutch, French, and Swedish East India Companies.

The 'China' indicated in the term 'chinoiserie' represented in European people's mind a wider region of the globe that could embrace China itself, but also Japan, Korea, South-East Asia, India or even Persia.

[8] After the spread of Marco Polo's narrations, the knowledge of China held by the Europeans continued to derive essentially from reports made by merchants and diplomatic envoys.

Dating from the latter half of the 17th century a relevant role in this exchange of information was then taken up by the Jesuits, whose continual gathering of missionary intelligence and language transcription gave the European public a new deeper insight of the Chinese empire and its culture.

[11] According to Voltaire in his Art de la Chine, "The fact remains that four thousand years ago, when we did not know how to read, they [the Chinese] knew everything essentially useful of which we boast today.

"[12] Moreover, Indian philosophy was increasingly admired by philosophers such as Arthur Schopenhauer, who regarded the Upanishads as the "production of the highest human wisdom" and "the most profitable and elevating reading which...is possible in the world.

Some critics saw the style as "…a retreat from reason and taste and a descent into a morally ambiguous world based on hedonism, sensation and values perceived to be feminine.

Architect and author Robert Morris claimed that it "…consisted of mere whims and chimera, without rules or order, it requires no fertility of genius to put into execution.

As such, the direct imitation of Chinese designs in faience began in the late 17th century, was carried into European porcelain production, most naturally in tea wares, and peaked in the wave of rococo chinoiserie (c.

Tin-glazed pottery (see delftware) made at Delft and other Dutch towns adopted genuine blue-and-white Ming decoration from the early 17th century.

"[19] The aspects of Chinese painting that were integrated into European and American visual arts include asymmetrical compositions, lighthearted subject matter and a general sense of capriciousness.

Entire rooms, such as those at Château de Chantilly, were painted with chinoiserie compositions, and artists such as Antoine Watteau and others brought expert craftsmanship to the style.

[22] Pleasure pavilions in "Chinese taste" appeared in the formal parterres of late Baroque and Rococo German and Russian palaces, and in tile panels at Aranjuez near Madrid.

The monumental 163-foot Great Pagoda in the centre of the gardens, designed and built by William Chambers, exhibits strong English architectural elements, resulting in a product of combined cultures (Bald, 290).

Though the rise of a more serious approach in Neoclassicism from the 1770s onward tended to replace Oriental inspired designs, at the height of Regency "Grecian" furnishings, the Prince Regent came down with a case of Brighton Pavilion, and Chamberlain's Worcester china manufactory imitated "Imari" wares.

[citation needed] While classical styles reigned in the parade rooms, upscale houses, from Badminton House (where the "Chinese Bedroom" was furnished by William and John Linnell, ca 1754) and Nostell Priory to Casa Loma in Toronto, sometimes featured an entire guest room decorated in the chinoiserie style, complete with Chinese-styled bed, phoenix-themed wallpaper, and china.

[31] A single historical incident in which there was a "keen competition between Margaret, 2nd Duchess of Portland, and Elizabeth, Countess of Ilchester, for a Japanese blue and white plate,"[32] shows how wealthy female consumers asserted their purchasing power and their need to play a role in creating the prevailing vogue.

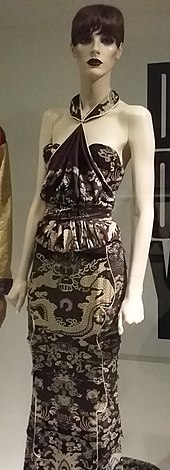

[33] Since the 17th century, Chinese arts and aesthetic were sources of inspiration to artists and creators,[34]: 52 and fashion designers when goods from oriental countries were widely seen for the first time in Western Europe.

According to the Ladies' Home Journal of June 1913, volume 30, issue 6:Interest in the political and civic activities of the new China, which is more or less world-wide at this time, led the designers of this page [p.26] and the succeeding one [p.27] to look to that country for inspiration for clothes that would be unique and new and yet fit in with present-day modes and the needs and environments of American women [...]Western approximations of Chinese and oriental music first began to be used in the mid-17th century in operas such as Purcell's The Fairy-Queen (1692) and Gluck's Le cinesi (1754).

[41] Jean-Jacques Rousseau included what he claimed was an authentic Chinese melody, the air chinois, in his 1768 Dictionary of Music, and it was re-used by Weber in his Overtura cinesa (1804).

[44] In the early 20th century French composers responded to the West's then utopian, nostalgic view of Chinese landscape and culture in pieces such as Pagodas (Debussy, 1903).

[45] There followed three major 20th century examples of musical chinoiserie: Mahler's Das Lied von der Erde (1908), Stravinsky's The Nightingale (1914), and Puccini's Turandot (1926).

[50] These pieces often incorporate Western cultural shorthand clichés of Chinese musical style, such as the oriental riff, making use of the pentatonic scale, often harmonized with open parallel fourths.

[52] Critics also describe a mannered "Chinese-esque" style of writing, such as that employed by Ernest Bramah in his Kai Lung stories, Barry Hughart in his Master Li & Number Ten Ox novels and Stephen Marley in his Chia Black Dragon series.