Beethoven quadrangle

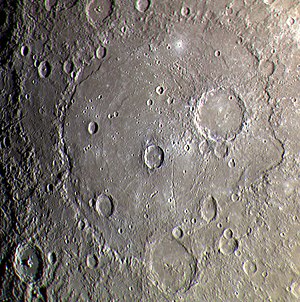

Generally, topography appears highly subdued because of the sun angle, and boundaries between map units are not clearly defined.

[1] Remnant ejecta blankets around parts of the Beethoven and Raphael basins are subdued in appearance and their margins poorly defined in places.

Surfaces of the plains units range in morphology from relatively level but rough to nearly flat and smooth; the latter terrain has intermediate albedo like that of the Cayley Formation or older maria on the Moon.

There, as in other regions of Mercury,[3] its surface reveals the outlines of many buried crater rim crests and knobby remnants of an older resurfaced terra.

The intercrater plains material is probably about the same age as the ejecta blanket around Beethoven basin: both units have a high crater density.

The intermediate plains material is widespread in intercrater areas in the west half of the quadrangle and fills floors of older craters and basins in the southern part.

Collectively, these materials impart a homogeneous appearance to the surface of the planet that is unlike the contrast in bright highlands and dark maria of the Moon.

Its absence may be due, in part, to fewer clusters of large young craters whose coalesced ejecta blankets could have yielded the coarsely textured, rough surfaces that characterize the unit in the Kuiper area.

Both of these conditions may promote, particularly on large structures,[1] more rapid isostatic adjustments that would be expressed by subdued topography and the premature “aging” of once-large topographic features.

In addition to the large single-ringed basins of Beethoven and Raphael, at least eight double-ringed craters exceeding 100 km in diameter occur in the quadrangle.

These craters range in age from c1 to c3 and, on a minor scale, their ejecta blankets provide stratigraphic horizons useful for the relative dating of material units in their vicinity.

An alternative model for central ring or peak formation was discussed by Melosh (1983), who suggested that they form as a result of rebound of fractured material analogous to the jet produced by a stone dropped into water.

This size limit seems to be generally applicable in the Beethoven quadrangle with the exception of the ringed crater Judah Ha-Levi (lat 11° N., long 109°), which has an inner rim-crest diameter of about 80 km.

Where the troughs are not clearly radial to crater or basin centers, they may be grabens; however, in most places they are difficult to distinguish from linear gouges produced by impact ejecta at low-angle ballistic trajectories.

Geologic evidence for the reconstruction of the evolutionary history of Mercury is less complete than for the Moon and Mars, for which orbiting spacecraft and landers have provided total or near-total coverage and high-resolution images.

The geologic record shows a period of decreasing meteoroid flux on all three, wherein the basins and large craters formed early in their crustal evolution were superseded by impacts of progressively smaller size.

The low density of small craters in the oldest class, c1, results from their destruction by impacts and obscuration by ejecta and volcanic material over a long period of mercurian history.

Possibly the plains units on Mercury are similar to the Cayley Formation on the Moon and consist largely of finely divided ejecta materials.