Mariner 10

Mariner 10 was an American robotic space probe launched by NASA on 3 November 1973, to fly by the planets Mercury and Venus.

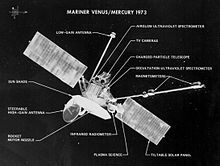

The mission objectives were to measure Mercury's environment, atmosphere, surface, and body characteristics and to make similar investigations of Venus.

Finally, the antennas would transmit this data to the Deep Space Network back on Earth, as well as receive commands from Mission Control.

[7] NASA set a strict limit of US$98 million for Mariner 10's total cost, which marked the first time the agency subjected a mission to an inflexible budget constraint.

[12][13][14] The spacecraft's electronics were intricate and complex: it contained over 32,000 pieces of circuitry, of which resistors, capacitors, diodes, microcircuits, and transistors were the most common devices.

The power subsystem used two redundant sets of circuitry, each containing a booster regulator and an inverter, to convert the panels' DC output to AC and alter the voltage to the necessary level.

Engineers considered folding the panels toward each other, making a V-shape with the main body, but tests found this approach had the potential to overheat the rest of the spacecraft.

Instead, a special paint was applied to exposed parts on the rocket so as to reduce heat flow from the nozzle to the delicate instruments on the spacecraft.

[9] The imaging system, the Television Photography Experiment, consisted of two 15 centimeters (5.9 in) Cassegrain telescopes feeding vidicon tubes.

[30] The entire imaging system was imperiled when electric heaters attached to the cameras failed to turn on immediately after launch.

JPL engineers found that the vidicons could generate enough heat through normal operation to stay just above the critical temperature of −40 °C (−40 °F); therefore they advised against turning off the cameras during the flight.

The occultation spectrometer scanned Mercury's edge as it passed in front of the Sun, and detected whether solar ultraviolet radiation was absorbed in certain wavelengths, which would indicate the presence of gas particles, and therefore an atmosphere.

[39] The airglow spectrometer detected extreme ultraviolet radiation emanating from atoms of gaseous hydrogen, helium, carbon, oxygen, neon, and argon.

The experiment's most important goal was to ascertain whether Mercury had an atmosphere, but would also gather data at Earth and Venus and study the interstellar background radiation.

The Scanning Electrostatic Analyzer was aimed toward the Sun and could detect positive ions and electrons, which were separated by a set of three concentric hemispherical plates.

Technicians filled a tank on the spacecraft with 29 kilograms (64 lb) of hydrazine fuel so that the probe could make course corrections, and attached squibs, whose detonation would signal Mariner 10 to exit the launch rocket and deploy its instruments.

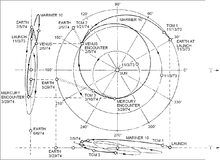

[52][53] The planned gravity assist at Venus made it feasible to use an Atlas-Centaur rocket instead of a more powerful but more expensive Titan IIIC.

The temporary orbit took the spacecraft one-third of the distance around Earth: this maneuver was needed to reach the correct spot for a second burn by the Centaur engines, which set Mariner 10 on a path towards Venus.

Never before had a planetary mission depended upon two separate rocket burns during the launch, and even with Mariner 10, scientists initially viewed the maneuver as too risky.

[59] Far from being an uneventful cruise, Mariner 10's three-month journey to Venus was fraught with technical malfunctions, which kept mission control on edge.

Immediately afterward, the star-tracker locked onto a bright flake of paint which had come off the spacecraft and lost tracking on the guide star Canopus.

Engineers initially feared that the star-tracker could mistake the much brighter Venus for Canopus, repeating the mishaps with flaking paint.

Earth occultation occurred between 17:07 and 17:11 UTC, during which the spacecraft transmitted X-band radio waves through Venus' atmosphere, gathering data on cloud structure and temperature.

[70] Overall, atmospheric temperature is higher closer to the planet's surface, but Mariner 10 found four altitudes where the pattern was reversed, which could signify the presence of a layer of clouds.

[71] Mariner 10's ultraviolet photographs were an invaluable information source for studying the churning clouds of Venus' atmosphere.

[74] The subsolar region was of particular interest: as the sun is straight overhead, it imparts more solar energy to this area than other part of the planet.

"Cells" of air lifted by convection, each up to 500 kilometers (310 mi) wide, were observed forming and dissipating within the span of a few hours; some had polygonal outlines.

[2] After losing roll control in October 1974, a third and final encounter, the closest to Mercury, took place on 16 March 1975, at a range of 327 kilometers (203 mi), passing almost over the north pole.

Engineering tests were continued until 24 March 1975,[2] when final depletion of the nitrogen supply was signaled by the onset of an un-programmed pitch turn.

[77] Mariner 10 also discovered that Mercury has a tenuous atmosphere consisting primarily of helium, as well as a magnetic field and a large iron-rich core.