Behavioural genetics

Behavioural genetics was founded as a scientific discipline by Francis Galton in the late 19th century, only to be discredited through association with eugenics movements before and during World War II.

In the latter half of the 20th century, the field saw renewed prominence with research on inheritance of behaviour and mental illness in humans (typically using twin and family studies), as well as research on genetically informative model organisms through selective breeding and crosses.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, technological advances in molecular genetics made it possible to measure and modify the genome directly.

Environmental influences also play a strong role, but they tend to make family members more different from one another, not more similar.

Selective breeding and the domestication of animals is perhaps the earliest evidence that humans considered the idea that individual differences in behaviour could be due to natural causes.

[2][3] Behavioural genetic concepts also existed during the English Renaissance, where William Shakespeare perhaps first coined the phrase "nature versus nurture" in The Tempest, where he wrote in Act IV, Scene I, that Caliban was "A devil, a born devil, on whose nature Nurture can never stick".

[3][4] Modern-day behavioural genetics began with Sir Francis Galton, a nineteenth-century intellectual and cousin of Charles Darwin.

[3] Galton was a polymath who studied many subjects, including the heritability of human abilities and mental characteristics.

One of Galton's investigations involved a large pedigree study of social and intellectual achievement in the English upper class.

[3] The primary idea behind eugenics was to use selective breeding combined with knowledge about the inheritance of behaviour to improve the human species.

[3] The eugenics movement was subsequently discredited by scientific corruption and genocidal actions in Nazi Germany.

[3] The field once again gained status as a distinct scientific discipline through the publication of early texts on behavioural genetics, such as Calvin S. Hall's 1951 book chapter on behavioural genetics, in which he introduced the term "psychogenetics",[7] which enjoyed some limited popularity in the 1960s and 1970s.

Behavioural geneticists using model organisms employ a range of molecular techniques to alter, insert, or delete genes.

[20] Animals commonly used as model organisms in behavioural genetics include mice,[21] zebra fish,[22] Drosophila,[23] and the nematode species C. elegans.

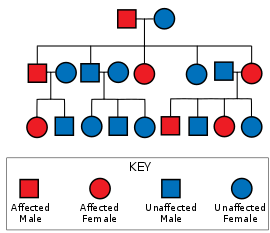

[26][30] The formulation rests on the basic observation that the variance in a phenotype is due to two sources, genes and environment.

Dropping the gene by environment interaction for simplicity (typical in twin studies) and fully decomposing the

[32] Once genotyped, genetic variants can be tested for association with a behavioural phenotype, such as mental disorder, cognitive ability, personality, and so on.

[3][59] Three major conclusions include:[3] It is clear from multiple lines of evidence that all researched behavioural traits and disorders are influenced by genes; that is, they are heritable.

[11][12] The conclusion that genetic influences are pervasive has also been observed in research designs that do not depend on the assumptions of the twin method.

[48] Such methods do not rely on the same assumptions as twin or adoption studies, and routinely find evidence for heritability of behavioural traits and disorders.

) in human studies are small, negligible, or zero for the vast majority of behavioural traits and psychiatric disorders, whereas estimates of non-shared environmental effects (

[65] [non-primary source needed] Genetic effects on human behavioural outcomes can be described in multiple ways.

[26] One way to describe the effect is in terms of how much variance in the behaviour can be accounted for by alleles in the genetic variant, otherwise known as the coefficient of determination or

(denoting the slope in a regression equation), or, in the case of binary disease outcomes by the odds ratio

[73] There are a small handful of replicated and robustly studied exceptions to this rule, including the effect of APOE on Alzheimer's disease,[74] and CHRNA5 on smoking behaviour,[67] and ALDH2 (in individuals of East Asian ancestry) on alcohol use.

The risk alleles within such variants are exceedingly rare, such that their large behavioural effects impact only a small number of individuals.

Examples include variants within APP that result in familial forms of severe early onset Alzheimer's disease but affect only relatively few individuals.

[66] In response to general concerns about the replicability of psychological research, behavioural geneticists Robert Plomin, John C. DeFries, Valerie Knopik, and Jenae Neiderhiser published a review of the ten most well-replicated findings from behavioural genetics research.

Major areas of controversy have included genetic research on topics such as racial differences, intelligence, violence, and human sexuality.

[3] For example, the notion of heritability is easily misunderstood to imply causality, or that some behaviour or condition is determined by one's genetic endowment.