The Troubles in Ulster (1920–1922)

On 20 March 1914, the Curragh Mutiny occurred in which British Army officers vowed to resign or be dismissed if they were ordered to enforce the Home Rule Act.

[22][23] Other events which contributed to the outbreak of violence were the assassinations of senior British Army officers, policemen and politicians: RIC Divisional Commissioner Lt Col Gerald Smyth (July 1920), RIC District Inspector Swanzy (August 1920), Belfast City Councilman William J. Twaddell (May 1922), and British Army Field Marshall Sir Henry Wilson (the Military Advisor to the Ulster Government).

IRA volunteers Reginald Dunne and Joseph O'Sullivan (both of whom had served as British soldiers in World War I) were apprehended and found guilty of Wilson's murder.

[24] In June 1920, the Ulster Unionist Council remobilized the UVF with one of the leading organizers being the future, long term Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Basil Brooke (1943–1963).

"[25] The British Prime Minister, Lloyd George, had around the same time formed the Black and Tans and Auxiliary Division made up of returning soldiers to help bolster the RIC, but they quickly became notorious for their actions against nationalists.

However, Unionists became dismayed when an electoral pact saw Sinn Féin and the Nationalist Party gaining control of ten urban councils within the area due to become Northern Ireland.

[27] Irish nationalist newspaper the Derry Journal heralded the fall of unionist control over Londonderry Corporation, declaring "No Surrender – Citadel Conquered".

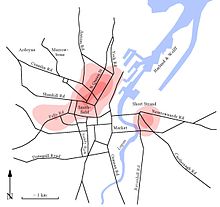

In response, loyalists reformed the UVF in the city and mounted roadblocks, Catholics crossing Carlisle Bridge were mistreated, resulting in one who had returned injured from the war being killed.

Eventually, on 23 June 1920, 1,500 British troops arrived in Derry to restore order, martial law was declared in the city, and a destroyer was anchored on the Foyle overlooking the Guildhall.

[34] The events that triggered the 1912 workplace expulsions were the introduction of the Home Rule for Ireland Act in April 1912 and another incident which took place in Castledawson, County Londonderry when a member of the Ancient Order of Hibernians snatched a British flag from the hands of a young boy – resulting in rioting.

[38] At this time in Belfast, Catholics made up a quarter of the city's population but accounted for up two-thirds of those killed, they suffered 80% of the property destruction and comprised 80% of refugees.

A Loyalist mob attempted to burn down a Catholic convent on Newtownards Road; soldiers guarding the building responded opened fire, wounding 15 Protestants, three of them fatally.

[49] The leader of the Ulster Unionist Party and the soon to be Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, Sir James Craig, made his feelings on the expulsions clear when he visited the shipyards: "Do I approve of the actions you boys have taken in the past?

[56] In the 1920s, temporary Peace lines (walls) were built in the area adjacent to the Harland & Wolff shipyards in Belfast and made permanent in 1969, following the outbreak of the 1969 Northern Ireland riots.

[67] Smyth was from a wealthy Protestant family in the northern town of Banbridge, County Down and his large funeral was held there on 21 July, the same day as the Belfast shipyard expulsions.

[69][70] Sectarian intimidation and violence continued in Banbridge and areas north of the town (the Bann Valley) throughout August and September 1920 with approximately 1,000 more Catholics being expelled from their jobs.

[87] In September 1920, Unionist leader James Craig wrote to the British government demanding that a special constabulary be recruited from the ranks of the loyalist, paramilitary organization the UVF.

[88] The Ulster Special Constabulary (USC), commonly called the "B-Specials" or "B Men" was formed in October 1920 and, in the words of historian Michael Hopkinson, "amounted to an officially approved UVF".

Patrick McAteer, a local farm worker, was fatally wounded on the same day roughly half a mile from the ambush site by soldiers when he failed to halt when challenged.

[108] Twenty eight people were killed or fatally wounded (including twelve Catholics and six Protestants) from the beginning of the truce (which began at noon on 11 July 1921) and into the following week.

[116] On 22 February 1921 in the small town of Mountcharles, County Donegal, the IRA attacked a mixed patrol of military and police, one RIC officer was killed and a soldier was wounded during a 30 minute exchange of gunfire.

[125] In response, on the night of 7–8 February, IRA units crossed into Northern Ireland and captured 40 Special Constables and prominent Loyalists in Fermanagh and Tyrone.

The USC unit was travelling by train from Belfast to Enniskillen (both in Northern Ireland), but the Irish Provisional Government was unaware British forces would be crossing through its territory.

[132] One of the most infamous sectarian attacks in Belfast during this period were the McMahon killings (24 March 1922), in which five Catholic family members and an employee were shot dead by gunmen who broke into their home.

[149] Woods was quoted on this attack: "The whole Loyalist population is at a loss to know how such a raid could be attempted during curfew hours on the headquarters in Belfast and the largest barrack in Ireland.

[156] Because of the harsh measures of the Special Powers Act many northern IRA men fled to the relative safety of County Donegal and reported for duty to the senior leader there - Charlie Daly.

After the killings, the A-Specials claimed they were attacked by the IRA and returned fire, but a British government inquiry, which was declassified almost a century later, concluded that the constabulary's version of events was false.

[165][167] James Craig, Prime Minister of Northern Ireland, telegrammed Winston Churchill, Secretary of State for the Colonies, to request that British troops be sent to drive out the IRA.

The leader of the IRA in Belfast (Seamus Woods) stated just how hard operations had become: "The enemy are continually raiding and arresting; the heavy sentences and particularly the flogging making the civilians very loath to keep wanted men or arms".

[81] Historians have argued that although the term "pogrom" could be used to describe the large-scale assaults on Catholics (June 1920), but the resultant counterattacks produced a situation similar to a civil war.