Bell

Most bells have the shape of a hollow cup that when struck vibrates in a single strong strike tone, with its sides forming an efficient resonator.

[1] Later, bells were made to commemorate important events or people and have been associated with the concepts of peace and freedom.

[3] It is popularly[4] but not certainly[3] related to the former sense of to bell (Old English: bellan, 'to roar, to make a loud noise') which gave rise to bellow.

[5] The earliest archaeological evidence of bells dates from the 3rd millennium BCE, and is traced to the Yangshao culture of Neolithic China.

[11] The book of Exodus in the Bible notes that small gold bells were worn as ornaments on the hem of the robe of the high priest in Jerusalem.

They also used them in the home, as an ornament and emblem, and bells were placed around the necks of cattle and sheep so they could be found if they strayed.

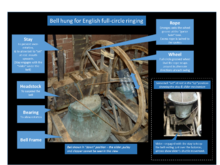

Such bells are either fixed in a static position ("hung dead") or mounted on a beam (the "headstock") so they can swing to and fro.

In some places, such as the Salzburg Cathedral, the clapper is held against the sound bow with an electric clasp as the bell swings up.

Occasionally the clappers have leather pads (called muffles) strapped around them to quieten the bells when practice ringing to avoid annoying the neighbourhood.

In the Roman Catholic Church and among some High Lutherans and Anglicans, small hand-held bells, called Sanctus or sacring bells,[15] are often rung by a server at Mass when the priest holds high up first the host and then the chalice immediately after he has said the words of consecration over them (the moment known as the Elevation).

Suzui, a homophone meaning both "cool" and "refreshing", are spherical bells which contain metal pellets that produce sound from the inside.

Jain, Hindu and Buddhist bells, called "Ghanta" (IAST: Ghaṇṭā) in Sanskrit, are used in religious ceremonies.

Steel was tried during the busy church-building period of mid-19th-century England, because it was more economical than bronze, but was found not to be durable and manufacture ceased in the 1870s.

[20] The core is built on the base-plate using porous materials such as coke or brick and then covered in loam well mixed with straw and horse manure.

The outside of the mould is made within a perforated cast-iron case, larger than the finished bell, containing the loam mixture which is shaped, dried and smoothed in the same way as the core.

The clamped mould is supported, usually by being buried in a casting pit to bear the weight of metal and to allow even cooling.

Molten bell metal is poured into the mould through a box lined with foundry sand.

Much effort has been expended over the centuries to find the shape which will produce the harmonically tuned bell.

The accompanying musical staves show the series of harmonics which are generated when a bell is struck.

Pieter and François Hemony in the 17th century reliably cast many bells for carillons of unequalled quality of tuning for the time, but after their death, their guarded trade secrets were lost, and not until the 19th century were bells of comparable tuning quality cast.

Tuning is undertaken by clamping the bell on a large rotating table and using a cutting tool to remove metal.

[25] The thickness of a church bell at its thickest part, called the "sound bow", is usually one thirteenth its diameter.

Scientists at the Technical University in Eindhoven, using computer modelling, produced bell profiles which were cast by the Eijsbouts Bellfoundry in the Netherlands.

The ancient Chinese bronze chime bells called bianzhong or zhong / zeng (鐘) were used as polyphonic musical instruments and some have been dated at between 2000 and 3600 years old.

However, the remarkable secret of their design and the method of casting—known only to the Chinese in antiquity—was lost in later generations and was not fully rediscovered and understood until the 20th century.

[33] The bells of Marquis Yi—which were still fully playable after almost 2500 years—cover a range of slightly less than five octaves but thanks to their dual-tone capability, the set can sound a complete 12-tone scale—predating the development of the European 12-tone system by some 2000 years—and can play melodies in diatonic and pentatonic scales.

[34] Another related ancient Chinese musical instrument is called qing (磬 pinyin qìng) but it was made of stone instead of metal.

Several of these metal tubes which are struck manually with hammers, form an instrument named tubular bells or chimes.

In Scotland, up until the nineteenth century, it was the tradition to ring a dead bell, a form of handbell, at the death of an individual and at the funeral.

[35] Numerous organizations promote the ringing, study, music, collection, preservation and restoration of bells,[36] including: