Solenoid

A solenoid (/ˈsoʊlənɔɪd/[1]) is a type of electromagnet formed by a helical coil of wire whose length is substantially greater than its diameter,[2] which generates a controlled magnetic field.

The coil can produce a uniform magnetic field in a volume of space when an electric current is passed through it.

André-Marie Ampère coined the term solenoid in 1823, having conceived of the device in 1820.

The helical coil of a solenoid does not necessarily need to revolve around a straight-line axis; for example, William Sturgeon's electromagnet of 1824 consisted of a solenoid bent into a horseshoe shape (similarly to an arc spring).

Solenoids provide magnetic focusing of electrons in vacuums, notably in television camera tubes such as vidicons and image orthicons.

These solenoids, focus coils, surround nearly the whole length of the tube.

"Continuous" means that the solenoid is not formed by discrete finite-width coils but by many infinitely thin coils with no space between them; in this abstraction, the solenoid is often viewed as a cylindrical sheet of conductive material.

This is a derivation of the magnetic flux density around a solenoid that is long enough so that fringe effects can be ignored.

We confirm this by applying the right hand grip rule for the field around a wire.

If we wrap our right hand around a wire with the thumb pointing in the direction of the current, the curl of the fingers shows how the field behaves.

Since we are dealing with a long solenoid, all of the components of the magnetic field not pointing upwards cancel out by symmetry.

By Ampère's law, we know that the line integral of B (the magnetic flux density vector) around this loop is zero, since it encloses no electrical currents (it can be also assumed that the circuital electric field passing through the loop is constant under such conditions: a constant or constantly changing current through the solenoid).

We have shown above that the field is pointing upwards inside the solenoid, so the horizontal portions of loop c do not contribute anything to the integral.

Since we can arbitrarily change the dimensions of the loop and get the same result, the only physical explanation is that the integrands are actually equal, that is, the magnetic field inside the solenoid is radially uniform.

A similar argument can be applied to the loop a to conclude that the field outside the solenoid is radially uniform or constant.

This last result, which holds strictly true only near the center of the solenoid where the field lines are parallel to its length, is important as it shows that the flux density outside is practically zero since the radii of the field outside the solenoid will tend to infinity.

An intuitive argument can also be used to show that the flux density outside the solenoid is actually zero.

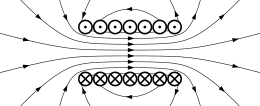

Magnetic field lines only exist as loops, they cannot diverge from or converge to a point like electric field lines can (see Gauss's law for magnetism).

The magnetic field lines follow the longitudinal path of the solenoid inside, so they must go in the opposite direction outside of the solenoid so that the lines can form loops.

Of course, if the solenoid is constructed as a wire spiral (as often done in practice), then it emanates an outside field the same way as a single wire, due to the current flowing overall down the length of the solenoid.

Applying Ampère's circuital law to the solenoid (see figure on the right) gives us where

The inclusion of a ferromagnetic core, such as iron, increases the magnitude of the magnetic flux density in the solenoid and raises the effective permeability of the magnetic path.

This is expressed by the formula where μeff is the effective or apparent permeability of the core.

Continuous means that the solenoid is not formed by discrete coils but by a sheet of conductive material.

The magnetic field can be found using the vector potential, which for a finite solenoid with radius R and length l in cylindrical coordinates

[13] The calculation of the intrinsic inductance and capacitance cannot be done using those for the conventional solenoids, i.e. the tightly wound ones.

[18] This, and the inductance of more complicated shapes, can be derived from Maxwell's equations.

Similar analysis applies to a solenoid with a magnetic core, but only if the length of the coil is much greater than the product of the relative permeability of the magnetic core and the diameter.

That limits the simple analysis to low-permeability cores, or extremely long thin solenoids.

Note that since the permeability of ferromagnetic materials changes with applied magnetic flux, the inductance of a coil with a ferromagnetic core will generally vary with current.