Benty Grange hanging bowl

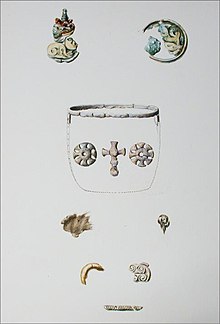

All that remains are parts of two escutcheons: bronze frames that are usually circular and elaborately decorated, and that sit along the outside of the rim or at the interior base of a hanging bowl.

The grave had probably been looted by the time of Bateman's excavation, but still contained high-status objects suggestive of a richly furnished burial, including the hanging bowl and the boar-crested Benty Grange helmet.

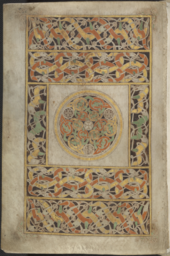

Although three escutcheons from a hanging bowl at Faversham also contain dolphin-like creatures, the Benty Grange design is most closely paralleled by Insular manuscripts, particularly figures in the Durham Gospel Fragment and the Book of Durrow.

[1] The hooks project from escutcheons: bronze plates or frames that are usually circular or oval, that are frequently elaborately decorated, and that are riveted or soldered (or occasionally both) to the bowl.

[2] They appear to have been manufactured by Celtic makers in Britain in the post-Roman period; examples were also used by Anglo-Saxons (who likely received bowls via trade) and, later, by Vikings.

[28][note 2] The reconstructed design shows three ribbon-style creatures resembling dolphins or fish, depicted in and arranged in a circle with each biting the tail of the one in front.

[36] Bateman remarked on this as early as 1861, noting that similar patterns were used in "several manuscripts of the [seventh] Century, for the purpose of decorating the initial letters".

[47][48] The Benty Grange hanging bowl is dated by most experts to the second half of the seventh century, based on its design and the associated finds from the barrow in which it was found.

[44] Given the presence of a helmet and cup with silver crosses, wrote Audrey Ozanne, "[t]he straightforward interpretation of this find would seem to be that it dates from a period subsequent to the official introduction of Christianity into Mercia in 655".

[57] Thomas Bateman, an archaeologist and antiquarian who led the excavation,[note 3] described Benty Grange as "a high and bleak situation";[56] its barrow, which still survives, is prominently located by a major Roman road,[60] now roughly parallel to the A515 in the area,[61] possibly to display the burial to passing travellers.

[62][64] The seventh-century Peak District was a small buffer province between Mercia and Northumbria, occupied, according to the Tribal Hidage, by the Anglo-Saxon Pecsæte.

[65][66][note 4] The area came under the control of the Mercian kingdom around the eighth century;[66] the Benty Grange and other rich barrows suggest that the Pecsæte may have had their own dynasty beforehand, but there is no written evidence for this.

[73] Bateman suggested a body once lay at its centre, flat against the original surface of the soil;[56][75] what he described as the one remnant, strands of hair, is now thought to be from a cloak of fur, cowhide or something similar.

[24] Also found were "a knot of very fine wire", some "thin bone variously ornamented with lozenges &c." attached to silk, but that soon decayed when exposed to air, and the Benty Grange hanging bowl.

[22][32][46] As Bateman described it The other articles found in the same situation are principally personal ornaments, of the same scroll pattern as those figured at page 25 of the Vestiges of the Antiquities of Derbyshire;[84]—of these enamels, there were two upon copper, with silver frames; and another of some composition which fell to dust almost immediately: the prevailing colour in all is yellow.

On 27 October 1848 he reported his discoveries, including the helmet, cup, and hanging bowl, at a meeting of the British Archaeological Association,[90][91][92] and in 1855 they were catalogued along with other objects from the Benty Grange barrow.

[94] It was displayed at the Weston Park Museum through 1893, at which point the younger Bateman, having spent his father's fortune, was forced to sell by order of chancery.

[73] The list entry notes that "[a]lthough the centre of Benty Grange [barrow] has been partially disturbed by excavation, the monument is otherwise undisturbed and retains significant archaeological remains.

[104] The finds were included in his 1855 catalogue of his collection,[105] and shortly before his death, Bateman revised and expanded upon his 1848 account in his 1861 book Ten Years' Digging in Celtic and Saxon Grave Hills.

[108][109] It was frequently mentioned in the literature thereafter,[36] including reconstructions by T. D. Kendrick in 1932 and 1938,[110][111] Françoise Henry in 1936,[112] Audrey Ozanne in 1962–1963,[113] George Speake in 1980,[114] and Jane Brenan in 1991.