Bermuda Militia (1612–1687)

What fate ultimately befell those two colonies is unclear, but the third established, Jamestown, spent its first years teetering on the same knife-edge between the threats of the Spanish, the Native nations, starvation, and disease.

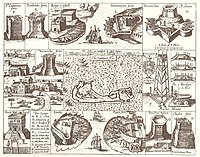

Under Moore's replacement, Governor Nathaniel Butler, 1619–1622, the detachment at each of the forts was re-organized to include several militia men under a trained artillery captain.

Titled The Somers Isles Company, it continued to operate Bermuda as a commercial venture until it, too, was dissolved by King Charles II in 1684.

The dissolution of the company also meant the end of the system of indentured servitude, which had ensured a cheap labour pool, preventing slavery becoming the basis of the economy, as it had in other agricultural colonies.

At the end of the first century of settlement, Bermuda's free and enslaved Blacks and Native Americans were still a small minority (which grew rapidly in the 18th century by combining with the Irish and Scots slaves, and a significant part of what might be termed the White Anglo population, dividing the populace into two demographic groupings, referred to as 'White' and 'Black' Bermudians).

The organization and efficiency of the militia progressed as the colony did, but, nonetheless, on arriving to begin his term as governor in 1687, Sir Robert Robinson, a naval officer, found his predecessor had failed to fulfill orders received in 1683, to ensure the proper maintenance of the fortifications and guns, and to keep them operations-ready day and night.