Architecture of Bermuda

The archipelago's isolation, environment, climate, and scarce resources have been key driving points, though inspiration from Europe, the Caribbean and the Americas is evident.

The archetypical Bermuda house is a low, squared building with a stepped, white roof and pastel-painted walls, both of which are made out of stone.

The first settlers built using the native and abundant Bermuda cedar, but such structures were rarely able to withstand either the normal winds or the occasional hurricane.

Though usually only one storey tall, most were built facing out from slopes (possibly to preserve the comparatively fertile valleys for agriculture, a dominant industry until the 20th century[5]), thus necessitating a set of steps to the front entrance.

Kitchens were also distinctive, occasionally placed in out-buildings or in basements and noted for the use of wide, raised chimneys possibly inspired by the open hearth.

[9] The earliest roofing was made of palmetto thatch but, partially from encouragement from the colonial government,[10] stone shingles slowly came to be preferred.

[6] A distinctive style of Bermudian roof developed, with a stepped profile of limestone slabs, grouted to make it impermeable and to stay clean.

Square, instead of the cylindrical of their Neo-Classical inspiration, these pillars were crowned with capitals of heterodox stone slabs stacked on top of each other to give a geometric pattern.

Finally, the roofs were coated with a mixture of lime, sand and water and, when available, turtle and whale oil to provide extra weather-proofing.

The walls, likewise, were often whitewashed, giving the island a faux snowcover if seen from a distance, though American author Mark Twain preferred to liken it to cake icing, "the white of marble...modest and retiring [in comparison]".

Rooms were added to the existing block, first giving buildings a cruciform appearance and later leaving no standard floor plan for the archetypical house.

Porches, backdoors and even basements featured simple arches, rarely decorated with capitals or voussoir-style keystones, that show inspiration from both Colonial Mexico and Saxon-Roman styles.

In time, the casement would be replaced by the sash window, and improved building techniques allowed window- and door-frames to be removed from the wallplate.

Porticos with simple limestone Doric order pillars topped by comparatively elaborate capitals were built, and upstairs windows were made smaller to recreate Classical optical perspective.

Initially most used either a plain square baluster or a "Chinese Chippendale" style, increasingly elaborate forms took precedence during the Victorian era.

The mock columns on the corners of buildings were replaced with quoins, also called "quoinces" and "longs and shorts", that alternated between being Headers or Stretchers.

[35] During the 20th century, expanded contact with the outside world has led to a considerable diversification of Bermuda's architecture, more so with commercial developments than residential, to the detriment of traditional styles.

[37] The Edwardian period saw the introduction of hybrid British-American bungalows marketed to the middle class; features included exposed eaves, windows gathered together and low roofs that were extended to cover porches.

Often these buildings were to provide cheap housing for imported labour, such as from the West Indies in the 1900s and 1930s, or during the Second World War for the builders of Kindley Air Force Base.

Wooden buildings became most prolific in Sandys parish, near to the Royal Naval Dockyard, followed by St. George's near the Kindley Field (used to house not only labourers but displaced residents) and finally Pembroke.

Prior to the outbreak of the Second World War, Cox Outerbridge imported wooden pre-fabricated buildings and created an affordable community on his estate in Pembroke.

The new structure, begun in the late 1950s and finished in 1960, was designed by Bermudian architect Wil Onions to copy styles from the traditional Bermuda cottage.

Generally used for private commercial purposes, the overseas styles began to take over the Hamilton skyline as international business grew, restricted only by a government mandate that no building be taller than the city's Cathedral.

During the selection process, the delegate from Mexico questioned why the site was not part of a serial nomination of Caribbean fortifications (considered by the United Nations to be part of a different region, Latin America, from Bermuda, Northern America, per the United Nations geoscheme)[51] and the delegate from Thailand questioned why ICOMOS wanted to apply criterion vi; it was decided to inscribe the site on the World Heritage List under criterion iv only.

In late 2008, the country's first LEED-accredited building was completed in Hamilton,[57][58] but the adoption of green technologies such as solar panels has been extremely slow.

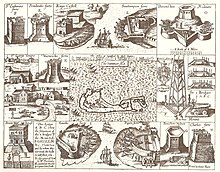

During the age of colonisation, risk of attack by the Spanish, French and Dutch led to a ring of wooden fortifications being built along the coastline.

These forts did not follow the conventional bastion-style that then prevailed in Europe; instead they most resembled the fortifications built under Henry VIII along the coast of southern England in the early 16th century.

[72] In the aftermath of the American Civil War, concerns over a landward attack on the Royal Naval Dockyard led to large tracts of the central parish of Devonshire being acquired by the British military.

Verandahs were often supported by iron columns that required constant painting, while roofs were lined with Welsh slate that was lost after every hurricane.

Though a few pretentious copycats still appeared among Bermuda's residences, around the start of the 20th century even the military was abandoning the style in favour of local techniques.