Bestiary

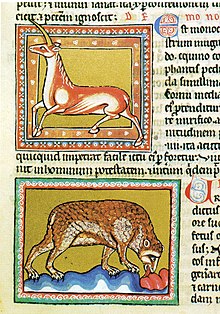

Originating in the ancient world, bestiaries were made popular in the Middle Ages in illustrated volumes that described various animals and even rocks.

For example, the pelican, which was believed to tear open its breast to bring its young to life with its own blood, was a living representation of Jesus.

Medieval Christians understood every element of the world as a manifestation of God, and bestiaries largely focused on each animal's religious meaning.

[1] The earliest bestiary in the form in which it was later popularized was an anonymous 2nd-century Greek volume called the Physiologus, which itself summarized ancient knowledge and wisdom about animals in the writings of classical authors such as Aristotle's Historia Animalium and various works by Herodotus, Pliny the Elder, Solinus, Aelian and other naturalists.

A few observations found in bestiaries, such as the migration of birds, were discounted by the natural philosophers of later centuries, only to be rediscovered in the modern scientific era.

The bestiary in the Queen Mary Psalter is found in the "marginal" decorations that occupy about the bottom quarter of the page, and are unusually extensive and coherent in this work.

The most widely known volucrary in the Renaissance was Johannes de Cuba's Gart der Gesundheit[7] which describes 122 birds and which was printed in 1485.

[8] The contents of medieval bestiaries were often obtained and created from combining older textual sources and accounts of animals, such as the Physiologus.

Descriptions of creatures such as dragons, unicorns, basilisk, griffin and caladrius were common in such works and found intermingled amongst accounts of bears, boars, deer, lions, and elephants.

[12] This lack of separation has often been associated with the assumption that people during this time believed in what the modern period classifies as nonexistent or "imaginary creatures".

The historian of science David C. Lindberg pointed out that medieval bestiaries were rich in symbolism and allegory, so as to teach moral lessons and entertain, rather than to convey knowledge of the natural world.

[14] With animals being a part of religion before bestiaries and their lessons came out, they were influenced by past observations of meaning as well as older civilizations and their interpretations.

John Henry Fleming's Fearsome Creatures of Florida[16] (Pocol Press, 2009) borrows from the medieval bestiary tradition to impart moral lessons about the environment.