Bet hedging (biology)

Other examples of biological bet hedging include female multiple mating,[2] foraging behavior in bumble bees,[3] nutrient storage in rhizobia,[4] and bacterial persistence in the presence of antibiotics.

[6] An example of this would be an organism producing clutches with a constant egg size that may not be optimal for any environmental condition, but result in the lowest overall variance.

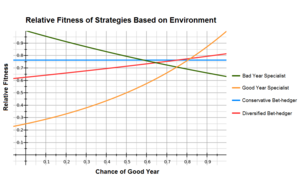

[6] Unlike conservative and diversified bet hedging strategies, adaptive coin flipping is not concerned with minimizing the variation in fitness between years.

As bet hedging involves a stochastic switching between phenotypes across generations,[12] prokaryotes are able to display this phenomenon quite nicely due to their ability to reproduce quickly enough to track evolution in a single population over a short period of time.

This rapid rate of reproduction has allowed for the study of bet hedging in labs through experimental evolution models.

In one example, the bacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti stores carbon and energy in a compound known as poly-3-hydroxybutyrate (PHB) in order to withstand carbon-deficient environments.

When starved, S. meliloti populations begin to display bet hedging by forming two non-identical daughter cells during binary fission.

In a given population of this bacteria, persister cells exist with the ability to arrest their growth, which leaves them unaffected by dramatic changes to the environment.

Because bet hedging produces phenotypically diverse offspring randomly in order to survive catastrophic conditions, it is difficult to develop treatments for bacterial infections, as bet hedging may ensure the survival of its species within its host, heedless to the antibiotic used.

In example, West Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) have been hypothesized to have major histocompatibility complex (MHC)-dependent mating systems, which have been shown in other species to be important for determining disease resistance among offspring.

[15] A second example among vertebrates is the marsupial species Sminthopsis macrour, which use a torpor strategy in order to reduce their metabolic rate to survive environmental changes.

Diaptomus sanguineus, an aquatic crustacean species found in many ponds of the Northeast United States, is one of the most well-studied examples of bet hedging.

This species uses a form of diversified bet hedging called germ banking, in which emergence timing among offspring from a single clutch is highly variable.

In Diaptomus sanguineus, germ banking occurs when parents produce dormant eggs prior to annual environmental shifts that yield increased risk for developing offspring.

Scientists believe multiple paternity has evolved in response to virgin insemination by low quality secondary male mates who have not undergone selection through intrasexual fighting.

The sierra dome spider exhibits this behavior as a form of genetic bet hedging, reducing the risk of producing low quality offspring and contracting venereal disease.

This phenomenon is beneficial to fungi, but in some cases, it has harmful effects on humans, illustrating that bet hedging has clinical importance.

The abundance of this gene was shown to correlate with heat and stress resistance, and thus survival of the yeast micro-colonies under harsh conditions by using bet hedging.

This illustrates that by using bet hedging, pathogenic strains of this yeast that are harmful to humans are more difficult to treat.

Studying closely related plant species can help us understand more about the circumstances under which bet hedging evolves.

The classic example of bet hedging, delayed seed germination,[1] has been extensively studied in desert annuals.

[24][25][26] One four-year field study[24] found that populations in historically worse (drier) environments had lower germination rates.

"[28] In barrel medick (Medicago truncatula) four flavonoid controlling genes, in addition to peroxidases and thio/peroxiredoxins, "have been associated with differential dormancy along an aridity gradient (Renzi et al., 2020).