Beylik of Tunis

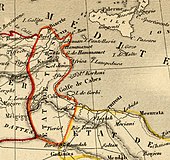

The Beylik of Tunis (Arabic: بايلك تونس) was a de facto independent state located in present-day Tunisia, formally part of the Ottoman Empire.

This committee was placed under the chairmanship of the reformed minister Kheireddine Pacha, and later devolved to Mustapha Ben Ismail, and it also included representatives of the creditor countries (Italy, England, and France).

With its creation, this office was the preserve of the Mamluks of foreign origin who were brought to Tunisia at a young age in order to serve the Royal Family and the Makhzen, such as Mustapha Khaznadar, Kheireddine Pacha and others.

[12] The Prime Minister, based on Section 9 of the Constitution, prepares the budget presented to him by the Ministry of Finance and submits it to Parliament in accordance with Article 64.

Husainid policy required a careful balance among several divergent parties: the distant Ottomans, the Turkish-speaking elite in Tunisia, and local Tunisians (both urban and rural, notables and clerics, landowners and remote tribal leaders).

Entanglement with the Ottoman Empire was avoided; yet religious ties to the Caliph were fostered, which increased the prestige of the Beys and helped in winning approval of the local ulama and deference from the notables.

Especially favored at the top were a handful of prominent families, Turkish-speaking, who were given business and land opportunities, as well as important posts in the government, depending on their loyalty to the Bey of Tunis.

[15][16] The French Revolution and reactions to it negatively affected European economic activity leading to shortages which provided business opportunities for Tunisia, i.e., regarding goods in high demand but short in supply, the result might be handsome profits.

The capable and well-regarded Hammouda Pasha (1782–1813) was Bey of Tunis (the fifth) during this period of prosperity; he also turned back an Algerian invasion in 1807, and quelled a janissary revolt in 1811.

[17] After the Congress of Vienna in 1815, Britain and France secured the Bey's agreement to cease sponsoring or permitting corsair raids, which had resumed during the Napoleonic conflict.

Yet different foreign business interests began to increasingly exercised control over domestic markets; imports of European manufactures often changed consumer pricing which could impact harshly on the livelihood of Tunisian artisans, whose goods did not fare well in the new environment.

[19][20] Activities of maritime corsairs were important at that time because independence from the sultan led to the decline of its financial support and Tunisia therefore had to increase the number of its catches at sea in order to survive.

The Tunisian Navy reached its peak during the reign of Hammouda I (1782–1814), where ships, leaving from the ports of Bizerte, La Goulette, Porto Farina, Sousse, Sfax and Djerba, seized Spanish, Corsican, Neapolitan, Venetians, etc.

[22] First of all, the treaties imposed requirements (possession of authorizations for ships and passports for people) and also identified the conditions for catches at sea (distance from the coast), so as to avoid possible abuses.

This was due to that period in which epidemics abounded in the Kingdom and led to human losses, in addition to the spread of Sufism in Tunisian culture, which used to call God as the owner of hidden kindness, influenced by Sidi Belhassen Chedly.

In 1830 the Bey accepted to enforce in Tunisia treaties, in which European merchants enjoyed extraterritorial privileges, including the right to have their resident consuls act as the judge in legal cases involving their national's civil obligations.

[33] To alleviate discontent, Ahmed obtained fatwas from the ulama beforehand from the Bach-mufti Sidi Brahim Riahi, which forbade slavery, categorically and without any precedent in the Arab Muslim world.

[34][35] However, although the abolition was accepted by the urban population, it was rejected (according to Ibn Abi Dhiaf) at Djerba, among the Bedouins, and among the peasants who required a cheap and obedient workforce.

The Fundamental Pact of 1857 (Arabic: عهد الأمان) is a declaration of the rights of Tunisians and inhabitants in Tunisia promulgated by Muhammad II on 10 September 1857, as part of the reforms of the Kingdom of Tunis.

[8] This pact provided revolutionary reforms: it proclaimed that everyone is equal before the law and before taxes, established freedom of religion and trade, and gave foreigners the right of access to property and exercise of all professions.

Considering this pact as a political genius act, Napoleon III awarded the grand cordon of the Legion of Honor with diamond insignia to Mohammed Bey at the Bardo Palace on 3 January 1858.

)[41] A number of Zitouna University professors who were loyal to reform and to Minister Kheireddine Pacha, such as Mahmoud Kabado, Salem Bouhageb, Bayram V, and Mohamed Snoussi were elected to the editorial in the government Journal.

The issuance of the Journal at that time was considered an important sign of modernizing the state and making individuals aware of the laws issued by the Bey and the government, although it was an opportunity for the political authority to give justification for its actions and legitimize its reforms.

[43] The text of 114 articles established a constitutional monarchy with a sharing of power between an executive branch consisting of the Bey and a prime minister, with important legislative prerogatives to a Supreme Council, creating a type of oligarchy.

Universal application of the mejba (head tax), under the equal taxation clause, incurred the wrath of those who had formerly been exempt: the military, scholars/teachers and government officials.

[44][45] Due to the ruinous policies of the Bey and his government, rising taxes and foreign interference in the economy, the country gradually experienced serious financial difficulties.

Because Tunisia quickly appeared as a strategic issue of great importance due to the geographical location of the country, between the western and eastern basin of the Mediterranean.

[46] The French and Italian consuls tried to take advantage of the Bey's financial difficulties, with France counting on the neutrality of England (unwilling to see Italy take control of the Suez Canal route) and benefiting from Bismarck, who wanted divert it from the question of Alsace-Lorraine.

[46] After the Congress of Berlin from 13 June to 13 July 1878, Germany and England allowed France to put Tunisia under protectorate and this to the detriment of Italy, which saw this country as its reserved domain.

The incursions of Khroumir "looters" into Algerian territory provided a pretext for Jules Ferry, supported by Léon Gambetta in the face of a hostile parliament, to stress the need to seize Tunisia.