Genesis creation narrative

[5] In this story, Elohim (the Hebrew generic word for "god") creates the heavens and the Earth in six days, and then rests on, blesses, and sanctifies the seventh (i.e., the Biblical Sabbath).

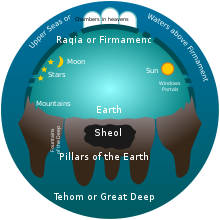

[8] The authors of the text were influenced by Mesopotamian mythology and ancient near eastern cosmology, and borrowed several themes from them, adapting and integrating them with their unique belief in one God.

[11] Scholarly writings frequently refer to Genesis as myth, a genre of folklore consisting primarily of narratives that play a fundamental role in a society.

[8] A sizeable minority of scholars believe that the first eleven chapters of Genesis, also known as the primeval history, can be dated to the 3rd century BCE based on discontinuities between the contents of the work and other parts of the Hebrew Bible.

Each had its own "history of origins," but the Persian promise of greatly increased local autonomy for all provided a powerful incentive to cooperate in producing a single text.

Traditional Jewish and evangelical scholars such as Collins explain this as a single author's variation in style in order to, for example, emphasize the unity and transcendence of "God", who created the heavens and Earth by himself, in the first narrative.

[38] Later Jewish thinkers, adopting ideas from Greek philosophy, concluded that God's Wisdom, Word and Spirit penetrated all things and gave them unity.

[41] The idea that God created the world out of nothing (creatio ex nihilo) has become central today to Islam, Christianity, and Judaism – indeed, the medieval Jewish philosopher Maimonides felt it was the only concept that the three religions shared[43] – yet it is not found directly in Genesis, nor in the entire Hebrew Bible.

[54] The cosmos created in Genesis 1 bears a striking resemblance to the Tabernacle in Exodus 35–40, which was the prototype of the Temple in Jerusalem and the focus of priestly worship of Yahweh; for this reason, and because other Middle Eastern creation stories also climax with the construction of a temple/house for the creator god, Genesis 1 can be interpreted as a description of the construction of the cosmos as God's house, for which the Temple in Jerusalem served as the earthly representative.

[60] Biblical scholars John Day and David Toshio Tsumura argue that Genesis 1:1 describes the initial creation of the universe, the former writing: "Since the inchoate earth and the heavens in the sense of the air/wind were already in existence in Gen. 1:2, it is most natural to assume that Gen. 1:1 refers to God's creative act in making them.

"[61][62] Other scholars such as R. N. Whybray, Christine Hayes, Michael Coogan, Cynthia Chapman, and John H. Walton argue that Genesis 1:1 describes the creation of an ordered universe out of preexisting, chaotic material.

[72] The phrase appears also in Jeremiah 4:23 where the prophet warns Israel that rebellion against God will lead to the return of darkness and chaos, "as if the earth had been 'uncreated'".

or, as the Psalmist echoed it, "He spoke and it was so," [Psalm 33:9] refers not to the utterance of the magic word, but to the expression of the omnipotent, sovereign, unchallengeable will of the absolute, transcendent God to whom all nature is completely subservient.

This was a matter of crucial importance to the Priestly authors, as the three pilgrimage festivals were organised around the cycles of both the sun and moon in a lunisolar calendar that could have either 12 or 13 months.

The meaning of this is unclear but suggestions include:[116][117] When in Genesis 1:26 God says "Let us make man", the Hebrew word used is adam; in this form it is a generic noun, "mankind", and does not imply that this creation is male.

Humanity is to extend the Kingdom of God beyond Eden, and, imitating the Creator-God, is to labour to bring the earth into its service, to the end of the fulfilment of the mandate.

[119] This would include the procreation of offspring, the subjugation and replenishment of the earth (e.g., the use of natural resources), dominion over creatures (e.g., animal domestication), labor in general, and marriage.

The Priestly author of Genesis appears to look back to an ideal past in which mankind lived at peace both with itself and with the animal kingdom, and which could be re-achieved through a proper sacrificial life in harmony with God.

Rest is both disengagement, as the work of creation is finished, but also engagement, as the deity is now present in his temple to maintain a secure and ordered cosmos.

[132] Before the man is created, the earth is a barren waste watered by an ’êḏ (אד); Genesis 2:6 of the King James Version has the translation "mist" for this word, following Jewish practice.

Eden may represent the divine garden on Zion, the mountain of God, which was also Jerusalem; while the real Gihon was a spring outside the city (mirroring the spring which waters Eden); and the imagery of the Garden, with its serpent and cherubs, has been seen as a reflection of the real images of the Temple of Solomon with its copper serpent (the nehushtan) and guardian cherubs.

In verse 17, God gives the "focal probationary proscription", that Adam must not eat of the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, which refers to "judicial discernment" (cf.

[146] The first woman is created out of one of Adam's ribs to be ezer kenegdo (עזר כנגדו ‘êzer kəneḡdō)[147] – a term notably difficult to translate – to the man.

This literature was dedicated to the composition of commentaries, homilies, and treatises concerned with the exegesis of the biblical creation narrative through ancient and medieval times.

[164] It has gained acceptance in modern times through the work of such theologians and scholars as Meredith G. Kline, Henri Blocher, John H. Walton and Bruce Waltke.

[167][page needed] Opponents of the framework interpretation include James Barr, Andrew Steinmann, Robert McCabe, and Ting Wang.

[168] Additionally, some conservative systematic theologians, such as Wayne Grudem and Millard Erickson, have criticised the framework interpretation, deeming it an unsuitable reading of the Genesis text.

[173] Reformed and evangelical scholar Bruce Waltke cautions against one such misreading: the "woodenly literal" approach, which leads to "creation science", but also to such "implausible interpretations" as the "gap theory", the presumption of a "young earth", and the denial of evolution.

Because the action of the primeval story is not represented as taking place on the plane of ordinary human history and has so many affinities with ancient mythology, it is very far-fetched to speak of its narratives as historical at all.

[175]Another scholar, Conrad Hyers, summed up the same thought by writing, "A literalist interpretation of the Genesis accounts is inappropriate, misleading, and unworkable [because] it presupposes and insists upon a kind of literature and intention that is not there.