Genesis flood narrative

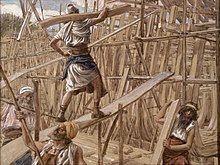

But God found one righteous man, Noah, and to him he confided his intention: "I am about to bring on the Flood ... to eliminate everywhere all flesh in which there is the breath of life ...

[6] But despite this disagreement on details the story forms a unified whole (some scholars see in it a "chiasm", a literary structure in which the first item matches the last, the second the second-last, and so on),[a] and many efforts have been made to explain this unity, including attempts to identify which of the two sources was earlier and therefore influenced the other.

[21] The name of the hero, according to the version concerned, was Ziusudra, Atrahasis, or Utnapishtim, all of which are variations of each other, and it is just possible that an abbreviation of Utnapishtim/Utna'ishtim as "na'ish" was pronounced "Noah" in Palestine.

[22] Numerous and often detailed parallels make clear that the Genesis flood narrative is dependent on the Mesopotamian epics, and particularly on Gilgamesh, which is thought to date from c. 1300–1000 BCE.

It is the Priestly source which adds more fantastic figures of a 150-day flood, which emerged by divine hand from the heavens and earth and took ten months to finally stop.

There is a text discovered from Ugarit known as RS 94.2953, consisting of fourteen lines telling a first-person account of how Ea appeared to the story's protagonist and commanded him to use tools to make a window (aptu) at the top of the construction he was building, and how he implemented this directive and released a bird.

[32] It asks why the world which God has made is so imperfect and of the meaning of human violence and evil, and its solutions involve the notions of covenant, law, and forgiveness.

Such echoes are seldom coincidental—for instance, the word used for ark is the same used for the basket in which Moses is saved, implying a symmetry between the stories of two divinely chosen saviours in a world threatened by water and chaos.

[37] In Genesis 1 God separates the "waters above the earth" from those below so that dry land can appear as a home for living things, but in the flood story the "windows of heaven" and "fountains of the deep" are opened so that the world is returned to the watery chaos of the time before creation.

[38] (This parallels the Babylonian flood story in the Epic of Gilgamesh, where at the end of rain "all of mankind had returned to clay," the substance of which they had been made.

In Jewish folklore, the sins in the antediluvian world included blasphemy, occult practices and preventing new traders from making profit.

When the flood commenced, God caused each raindrop to pass through Gehenna before it fell on earth for forty days so that it could scald the skin of sinners.

[48] Noah and his family are saved because they were able to build an ark or kawila (or kauila, a Mandaic term; it is cognate with Syriac kēʾwilā, which is attested in the Peshitta New Testament, such as Matthew 24:38 and Luke 17:27).

There is no evidence of such a severe genetic bottleneck at that period of time (~2,500 BC) either among humans or other animal species;[51] however, if the flood narrative is derived from a more localized event and describes a founder effect among one population of humans, certain explanations such as the events described by the Black Sea deluge hypothesis may elaborate on the historicity of the flood narrative.

[55][56] As with the Channeled Scablands of the state of Washington, breakthroughs of glacial ice dams are believed to have unleashed massive and sudden torrents of water to form the gorge some time between 600 and 900 AD.

[56] Some also relate the climate change phenomena associated with the Piora Oscillation, which triggered the collapse of the Uruk period,[57] with the Biblical flood myth.

[63] In 2020, archaeologists discovered evidence of a tsunami that destroyed middle Pre-Pottery Neolithic B coastal settlements in Tel Dor, Israel as it traveled between 3.5 to 1.5 km inland.

In 1823 the English theologian and natural scientist William Buckland interpreted geological phenomena as Reliquiæ Diluvianæ (relics of the flood) "Attesting the Action of an Universal Deluge".

[68] Lux Mundi, an 1889 volume of theological essays which marks a stage in the acceptance of a more critical approach to scripture, took the stance that readers should rely on the gospels as completely historical, but should not take the earlier chapters of Genesis literally.

Historian Ronald Numbers argues that an ideological connection by evangelical Christians wanting to challenge aspects of the scientific consensus that they believe contradict their interpretation of religious texts was first established by the publication of the 1961 book, The Genesis Flood.

By the 17th century, believers in the Genesis account faced the issue of reconciling the exploration of the New World and increased awareness of the global distribution of species with the older scenario whereby all life had sprung from a single point of origin on the slopes of Mount Ararat.

The obvious answer involved mankind spreading over the continents following the destruction of the Tower of Babel and taking animals along, yet some of the results seemed peculiar.

The resulting hypotheses provided an important impetus to the study of the geographical distribution of plants and animals, and indirectly spurred the emergence of biogeography in the 18th century.