Biblioteca Marciana

The collection was the result of Bessarion's persistent efforts to locate rare manuscripts throughout Greece and Italy and then acquire or copy them as a means of preserving the writings of the classical Greek authors and the literature of Byzantium after the fall of Constantinople in 1453.

The Venetian government was slow, however, to honour its commitment to suitably house the manuscripts with decades of discussion and indecision, owing to a series of military conflicts in the late-fifteenth and early-sixteenth centuries and the resulting climate of political uncertainty.

The library was ultimately built during the period of recovery as part of a vast programme of urban renewal aimed at glorifying the republic through architecture and affirming its international prestige as a centre of wisdom and learning.

[1][2] The Renaissance architect Andrea Palladio described it as "perhaps the richest and most ornate building that there has been since ancient times up until now" ("il più ricco ed ornato edificio che forse sia stato da gli Antichi in qua").

But beginning in the fifteenth century, the humanist emphasis on the knowledge of the classical world as essential to the formation of the Renaissance man led to a proliferation of court libraries, patronized by princely rulers, several of which provided a degree of public access.

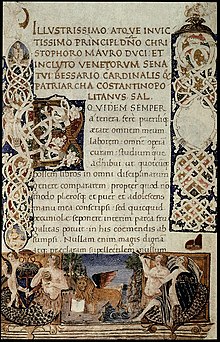

[10][11][12][13][note 1] The formal letter announcing the donation, dated 31 May 1468 and addressed to Doge Cristoforo Moro (in office 1462–1471) and the Senate, narrates that following the fall of Constantinople in 1453 and its devastation by the Turks, Bessarion had set ardently about the task of acquiring the rare and important works of ancient Greece and Byzantium and adding them to his existing collection so as to prevent the further dispersal and total loss of Greek culture.

[12][20] But under the influence of the humanist Paolo Morosini and his cousin Pietro, the Venetian ambassador to Rome, Bessarion annulled the legal act of donation in 1467 with papal consent, citing the difficulty readers would have had in reaching the monastery, located on a separate island.

[25] Despite the grateful acceptance of the donation by the Venetian government and the commitment to establish a library of public utility, the codices remained crated inside the Doge's Palace, entrusted to the care of the state historian under the direction of the procurators of Saint Mark de supra.

During Navagero's tenure (1516–1524), scholars made greater use of the manuscripts and copyists were authorized with more frequency to reproduce codices for esteemed patrons, including Pope Leo X, King Francis I of France, and Cardinal Thomas Wolsey, Lord High Chancellor of England.

[67][68][69] In the subsequent enquiry, Sansovino claimed that workmen had prematurely removed the temporary wooden supports before the concrete had set and that a galley in the basin of Saint Mark, firing her cannon as a salute, had shaken the building.

[note 25] The upper storey is characterized by a series of Serlians, so-called because the architectural element was illustrated and described by Sebastiano Serlio in his Tutte l'opere d'architettura et prospetiva, a seven-volume treatise for Renaissance architects and scholarly patrons.

The capitals with the egg-and-dart motif in the echinus and flame palmettes and masks in the collar may have been directly inspired by the Temple of Saturn in Rome and perhaps by the Villa Medicea at Poggio a Caiano by Giuliano da Sangallo.

[91][92] According to the architect's son, Francesco, Sansovino's design for the corner of the Doric frieze was much discussed and admired for its faithful adherence to the principles of Ancient Roman architecture as outlined by Vitruvius in De architectura.

[97][98][99] Rather than a two-dimensional wall, the façade is conceived as an assemblage of three-dimensional structural elements, including piers, arcades, columns, and entablatures layered atop one another to create a sense of depth,[1][100] which is increased by the extensive surface carvings.

With the exception of the arch in correspondence to the entry of the library which has Neptune holding a trident and Aeolus with a wind-filled sail, these figures represent allegories of non-specific rivers, characterized by the cornucopias and the urns with water flowing out.

In addition to the abundance of classical decorative elements – obelisks, keystone heads, spandrel figures, and reliefs – the Doric and Ionic orders, each with the appropriate frieze, cornice, and base, follow ancient Roman prototypes, giving the building a sense of authenticity.

Some of these paintings show mythological scenes derived from the writings of classical authors: Ovid's Metamorphoses and Fasti, Apuleius's The Golden Ass, Nonnus's Dionysiaca, Martianus Capella's The Marriage of Philology and Mercury, and the Suda.

They reflect the particular interest in the esotericism of the Hermetic writings and the Chaldean Oracles that enthused many humanists following the publication in 1505 of Horapollo's Ἱερογλυφικά (Hieroglyphica), the book discovered in 1419 by Cristoforo Buondelmonti and believed to be the key for deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics.

[102] The staircase largely represents the life of the embodied soul in the early stages of the ascent: the practice of the cardinal virtues, the study and contemplation of the sensible world in both its multiplicity and harmony, the transcendence of mere opinions (doxa) through dialectic, and catharsis.

[120][121][122] At the entry and on the landings, Sansovino repeated the Serlian element from the façade, making use of ancient columns taken from the dilapidated sixth-century Byzantine Church of Santa Maria del Canneto in Pola on the Istrian peninsula.

[138][note 35] The ceiling of the reading room is decorated with 21 roundels, circular oil paintings, by Giovanni de Mio, Giuseppe Salviati, Battista Franco, Giulio Licinio, Bernardo Strozzi, Giambattista Zelotti, Alessandro Varotari, Paolo Veronese, and Andrea Schiavone.

To varying degrees, the roundels that they produced for the ceiling of the reading room are consequently characterized by the emphasis on line drawing, the greater sculptural rigidity and artificial poses of the figures, and the overall dramatic compositions.

[155] The custodian was additionally tasked with showing the library to foreigners who visited primarily to admire the structure and the manuscripts, commenting in their travel diaries on the magnificence of the building, the ancient statuary, the paintings, and on the codices themselves.

[165] In 1811, the entire collection was moved to the former Hall of the Great Council in the Doge's Palace when the library, as a building, was transformed, together with the adjoining Procuratie Nuove, into an official residence for the viceroy of the Napoleonic Kingdom of Italy.

[173] Although an attempt was made in 1603 to increase the library's holdings by legally requiring that a copy of all books printed within the territory of the Venetian Republic be henceforth deposited in the Marciana, the law had little initial effect due to lack of enforcement.

[179] Elevated to the cardinalate in 1440, Bessarion enjoyed greater financial resources, and he added notable codices, including the precious tenth-century manuscripts of Alexander of Aphrodisias' works and of Ptolemy's Almagest that had once belonged to the library of Pope Boniface VIII.

[180][181] Around 1450, Bessarion began to place his ecclesiastical coat of arms on his books and assign shelf marks, an indication that the collection was no longer limited to personal consultation but that he intended to create a lasting library for scholars.

[186] These included his discoveries of the Posthomerica by Quintus Smyrnaeus and the Abduction of Helen by Coluthus, which would have otherwise been lost as a result of the Ottoman invasion of Otranto and the destruction of the monastic library of San Nicola di Casole [it] (Apulia) in 1480.

[189][190] Simultaneously, Bessarion assembled a parallel collection of Latin codices with a relative preponderance of works on patrology, philosophy (primarily the medieval Platonic and Aristotelian traditions), history, mathematics, and literature.

[195][196] Major additions include: Three hundred and three precious manuscripts along with 88 rare printed books were transferred to the Marciana in 1789 from the religious libraries of Santi Giovanni e Paolo, Sant'Andrea della Certosa, and S. Pietro Martire di Murano by order of the Council of Ten after an investigation into a theft revealed unsatisfactory security conditions.