Bicycle and motorcycle dynamics

[8] Although longitudinally stable when stationary, bikes often have a high enough center of mass and a short enough wheelbase to lift a wheel off the ground under sufficient acceleration or deceleration.

[2] In the early 19th century Karl von Drais, credited with inventing the two-wheeled vehicle variously called the laufmaschine, velocipede, draisine, and dandy horse, showed that a rider could balance his device by steering the front wheel.

Thus, by the end of the 19th century, Carlo Bourlet, Emmanuel Carvallo, and Francis Whipple had showed with rigid-body dynamics that some safety bicycles could actually balance themselves if moving at the right speed.

Bikes with negative trail (where the contact patch is in front of where the steering axis intersects the ground), while still rideable, are reported to feel very unstable.

For example, LeMond Racing Cycles offers [44] both with forks that have 45 mm of offset or rake and the same size wheels: The amount of trail a particular bike has may vary with time for several reasons.

A factor that influences the directional stability of a bike is wheelbase, the horizontal distance between the ground contact points of the front and rear wheels.

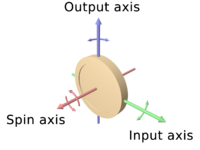

[11] Another factor that can also contribute to the self-stability of traditional bike designs is the distribution of mass in the steering mechanism, which includes the front wheel, the fork, and the handlebar.

[49] At low forward speeds, the precession of the front wheel is too quick, contributing to an uncontrolled bike's tendency to oversteer, start to lean the other way and eventually oscillate and fall over.

At high forward speeds, the precession is usually too slow, contributing to an uncontrolled bike's tendency to understeer and eventually fall over without ever having reached the upright position.

Between the two unstable regimes mentioned in the previous section, and influenced by all the factors described above that contribute to balance (trail, mass distribution, gyroscopic effects, etc.

Friction between the wheels and the ground then generates the centripetal acceleration necessary to alter the course from straight ahead as a combination of cornering force and camber thrust.

The angle of lean, θ, can easily be calculated using the laws of circular motion: where v is the forward speed, r is the radius of the turn and g is the acceleration of gravity.

A slight increase in the lean angle may be required on motorcycles to compensate for the width of modern tires at the same forward speed and turn radius.

A more-sophisticated model that allows a wheel to steer, adjust the path, and counter the torque of gravity, is necessary to capture the self-stability observed in real bikes.

In comparison, the lateral force on the front tire as it tracks out from under the motorcycle reaches a maximum of 50 N. This, acting on the 0.6 m (2 ft) height of the center of mass, generates a roll moment of 30 N·m.

While the moment from gyroscopic forces is only 12% of this, it can play a significant part because it begins to act as soon as the rider applies the torque, instead of building up more slowly as the wheel out-tracks.

[57] One documented example of someone successfully riding a rear-wheel steering bicycle is that of L. H. Laiterman at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, on a specially designed recumbent bike.

[58] Examination of the eigenvalues for bicycles with common geometries and mass distributions shows that when moving in reverse, so as to have rear-wheel steering, they are inherently unstable.

The resultant force of this side-slip occurs behind the geometric center of the contact patch, a distance described as the pneumatic trail, and so creates a torque on the tire.

[11] A highsider is a type of bike motion which is caused by a rear wheel gaining traction when it is not facing in the direction of travel, usually after slipping sideways in a curve.

[9] The need to keep a bike upright to avoid injury to the rider and damage to the vehicle limits the type of maneuverability testing commonly performed.

Energy added with a sideways jolt to a bike running straight and upright (demonstrating self-stability) is converted into increased forward speed, not lost, as the oscillations die out.

[74] It turns in the direction opposite of how it is initially steered, as described above in the section on countersteering The number of degrees of freedom of a bike depends on the particular model being used.

The fourth eigenvalue, which is usually stable (very negative), represents the castoring behavior of the front wheel, as it tends to turn towards the direction in which the bike is traveling.

On most bikes, when the front wheel is turned to one side or the other, the entire rear frame pitches forward slightly, depending on the steering axis angle and the amount of trail.

Bicycling Science author David Gordon Wilson points out that this puts upright bicyclists at particular risk of causing a rear-end collision if they tailgate cars.

A line similar to the one described above to analyze braking performance can be drawn from the rear wheel contact patch to predict if a wheelie is possible given the available friction, the center of mass location, and sufficient power.

On long or low bikes, however, such as cruiser motorcycles[90] and recumbent bicycles, the front tire will skid instead, possibly causing a loss of balance.

There are, however, situations that may warrant rear wheel braking[93] Expert opinion varies from "use both levers equally at first"[95] to "the fastest that you can stop any bike of normal wheelbase is to apply the front brake so hard that the rear wheel is just about to lift off the ground",[93] depending on road conditions, rider skill level, and desired fraction of maximum possible deceleration.

A challenge in vibration damping is to create compliance in certain directions (vertically) without sacrificing frame rigidity needed for power transmission and handling (torsionally).