Bilingual memory

[2] High proficiency provides mental flexibility across all domains of thought and forces them to adopt strategies that accelerate cognitive development.

[3] People who are bilingual integrate and organize the information of two languages, which creates advantages in terms of many cognitive abilities, such as intelligence, creativity, analogical reasoning, classification skills, problem solving, learning strategies, and thinking flexibility.

Languages in Contact, an essay published by Weinreich in 1953, proposed a model of bilingual memory organization that made the theoretical distinction between the lexical and conceptual level of representation.

[4] In 1954, Ervin and Osgood reformulated Weinreich's compound-coordinate representational model and placed further emphasis on the context of language learning, similar to the encoding specificity principle later proposed by Tulving in the 1970s.

This contrast between the destroyed and intact regions of the brain aids researchers in discovering the components of language processing.

[5] The techniques allowing researchers to observe brain activity in multilingual patients are conducted whilst the subject is simultaneously performing and processing a language.

Research has proposed that the entire production and comprehension of language is most likely regulated and managed by neural pools, whose stations of communication are in the cortical and subcortical regions.

[6] It has been shown that there are no grounds on which to assume the existence of distinct cerebral organization of separate languages in the bilingual brain.

The episodic memory holds the events from personal experiences in the past,[10] exists in subjective time and space, requires a conscious recollection and a controlled process.

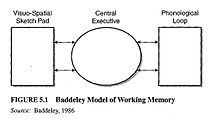

[15] Baddeley's model of working memory suggests the phonological loop, a slave system that is responsible for the rehearsal of verbal information and has been implicated in language acquisition.

The evidence suggests that working memory performance has a stronger relationship with general linguistic proficiency than it does with the acquisition of a second language.

[14] It has also been observed that there are no significant cross-language differences within bilinguals, providing further support for the hypothesis that working memory is not language specific.

[19] An explanation of this observation is that digits in English take longer to say and subvocally rehearse in the phonological loop, a component of Baddely's model of working memory.

[19] However, research has suggested that familiarity and long-term memory may play an important role and that differences are not strictly the result of subvocal rehearsal rates.

[1] Semantic memory does not require conscious thought, as it generally is automatic; it is not bound, except as interest links themes.

It is shown to increase the normal capacity and expose the person to new situations and different ways of organizing thoughts.

In the Concept Features Model, when words have highly prototypical, concrete referents (desk, juice) the translations in both languages would activate the same set of underlying semantic nodes.

In more conceptual and abstract referents (poverty, intelligence) translation equivalents activate different but overlapping sets of semantic nodes.

Overall they have better recall and recognition in letter fluency especially when older and more educated, but the more similarity between their two languages lessens the advantage, as when they are very close there is more overlap of information.

Mental lexicon refers to the permanent store of words in an individual's memory, and is thought to be organized in a semantic network.

However, when a word is phonologically similar in both languages, bilinguals produce fewer errors than individuals who are monolingual.

[26] Tip-of-the-tongue phenomenon occurs due to a temporary phonological encoding failure in the process of lexical retrieval.

[28] The first is called the weaker links hypothesis[28] and says that because bilinguals spread their time between two languages, the word-finding process is not used as often as it is for monolinguals.

[28] The dual-coding theory was first postulated by Paivio and Desrochers in 1980, and indicates that two systems are responsible for the encoding and retrieval of information from memory.

This theme continues into the bilingual adaptation of the dual-coding theory, which indicates that an individual's verbal representational systems for their two languages operate independently of one another, but also have associative connections with each other.

But if a person is required to translate the word "fierce" into the French version, this would entail the two language systems to have associative connections.

One of which deals with the constant finding that translated items are better recollected than the words that are directly recalled or require deriving synonyms for.

Therefore, it is important to reinstate these internal and external contexts in which a person encodes the memory in order to enhance recall.

[35] However, the results of this study also found that monolingual speakers in both Spanish and English tended to describe and recall information differently.

[40] In this study, it was found that bilinguals have larger resources having to do with task mixing and working memory that helped to prevent lower performance.