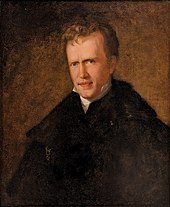

Bill Richmond

In the early 1790s, Richmond married a local English woman, whose name was probably Mary Dunwick, in a marriage recorded in Wakefield on 29 June 1791.

According to boxing writer Pierce Egan, the well-dressed, literate, and self-confident Richmond came on the receiving end of racist attitudes in Yorkshire.

[2] In 1777, Percy arranged for Richmond's freedom from Charlton, transportation to northern England, literacy education, and an apprenticeship with a cabinet maker in Yorkshire.

On 23 January 1804, Pitt and Richmond attended a boxing match featuring experienced boxer George Maddox.

He began training and seconding other fighters and was soon a regular attendee at the Fives Court, London's leading pugilistic exhibition venue on St Martin's Street in Westminster.

A spectator, William Windham, MP, later argued both boxers demonstrated skill and bravery as impressive as that displayed by British troops in their triumph that year at the Battle of Talavera.

Richmond's winnings allowed him to buy the Horse and Dolphin pub in St Martin's Street near Leicester Square in London.

Certainly, before the fight there was nervousness about the prospect of a Molineaux victory, with the Chester Chronicle reporting that "many of the noble patronizers [sic] of this accomplished art, begin to be alarmed, lest, to the eternal dishonour of our country, a negro should become the Champion of England!

Having lost money brokering and betting on the Molineaux-Cribb fight, Richmond had to sell the Horse and Dolphin and rebuild his fortune.

The victory over Davis encouraged Richmond to accept a fight with Tom Shelton, a respected contender who was about half his age.

"Impetuous men must not fight Richmond," Egan declared, "as in his hands they become victims to their own temerity … The older he grows, the better pugilist he proves himself … He is an extraordinary man."

In the 1820s Richmond ran a boxing academy, in which he trained many amateur boxers, including literary figures like William Hazlitt, Lord Byron, and American John Neal.

Williams writes that: The Richmond-as-hangman theory took root due to a coalescence of circumstantial evidence: numerous accounts of Hale's execution feature references to a black or mulatto hangman named Richmond (for example, the 1856 book Life of Nathan Hale: The Martyr Spy of the American Revolution, refers to the 'negro Richmond, the common hangman'); artwork of the execution published by Harpers Weekly in 1860 shows a black man holding the hanging rope; and then there is Richmond's connection to Percy and the British military, as well as the proximity of Staten Island to the site of Hale's execution in Manhattan.

Rather, as reports in the Gaines Mercury and Royal Gazette indicate, he was a Pennsylvania runaway with the same surname as Bill who ended up working as the hangman for the notorious Boston Provost Marshal William Cunningham.