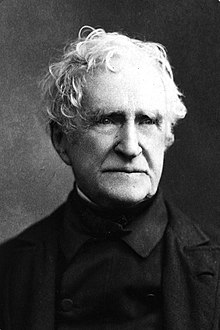

John Neal

By middle age, Neal had attained comfortable wealth and community standing in his native Portland, Maine, through varied business investments, arts patronage, and civic leadership.

Neal's mother, described by former pupil Elizabeth Oakes Smith as a woman of "clear intellect, and no little self-reliance and independence of will",[2] made up the lost family income by establishing her own school and renting rooms in her home to boarders.

[5] As an adolescent haberdasher and dry goods salesman in Portland and Portsmouth, Neal learned dishonest business practices like passing off counterfeit money[a] and misrepresenting merchandise quality and quantity.

[7] Laid off multiple times due to business failures resulting from the 1806 Non-importation Act against British imports, Neal traveled through Maine as an itinerant penmanship instructor, watercolor teacher, and miniature portrait artist.

[1][b] Neal's experience in business riding out the multiple booms and busts that eventually left him bankrupt at age twenty-two made him into a proud and ambitious young man who viewed reliance on his own talents and resources as the key to his recovery and future success.

[45] According to him, the catalyst to move to London was a dinner party with an English friend who quoted Sydney Smith's 1820 then-notorious remark, "in the four quarters of the globe, who reads an American book?".

Yet Brother Jonathan was not received as the great American novel and it failed to earn Neal the level of international fame he had hoped for, so he returned to the US no longer Cooper's chief rival.

[83] He used its pages to vindicate himself to fellow Portlanders,[84] critique American art[85] and drama,[86] host a discourse on the nature of New Englander identity,[87] advance his developing feminist ideas,[88] and encourage new literary voices, most of them women.

[90] Neal published three novels from material he produced in London and focused his new creative writing efforts on a body of short stories[91] that represents his greatest literary achievement.

[98] Also in 1836 he received an honorary master's degree from Bowdoin College, the same institution at which Neal made a living as a self-employed teenage penmanship instructor and that later educated the more economically privileged Nathaniel Hawthorne and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

[147] This was a "caustic assault"[147] on British literary elites viewed as aristocrats writing for personal amusement, in contrast to American authors as middle class professionals plying a commercial trade for sustenance.

[148] By mimicking the common and sometimes profane language of his countrymen in fiction, Neal hoped to appeal to a broader readership of minimally educated book buyers, thereby intending to guarantee the existence of an American national literature by ensuring its economic viability.

John Greenleaf Whittier, Edgar Allan Poe, Nathaniel Hawthorne, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow all received their first "substantial sponsorship or praise" in the magazine's pages.

[166] Like his magazine essays and lectures, Neal's stories challenged American socio-political phenomena that grew in the period leading up to and including Andrew Jackson's terms as US president (1829–1837): manifest destiny, empire building, Indian removal, consolidation of federal power, racialized citizenship, and the Cult of Domesticity.

[38] Inspired by Cooper's The Spy,[181] Neal based his story on historical research compiled a few years earlier while helping his friend Paul Allen write his History of the American Revolution.

[183] As "one of the most emphatic, even shrill examples of U.S. nationalistic literature",[183] it is "positively bristling with regional accents, from the New England twang of its protagonists through to bursts of patois in Virginian, Georgian, Scottish, Penobscot Indian, and Ebonics".

[199] Neal shows some initial influence from August Wilhelm Schlegel's Course of Lectures in Dramatic Art and Literature and Sir Joshua Reynolds's Discourses, but largely broke with those sensibilities over the course of the decade.

[200] By the late 1820s he came to dismiss history painting and show preference for "the unadulterated truth of the American locality and nature"[201] he found in portraits and landscapes, anticipating the rise of the Hudson River School.

[202] The positive attention Neal paid to American portrait painters trained in the "humbler contingencies"[201] of sign painting and applied arts was accompanied by his acknowledgment of the artist's often conflicting priorities: preserving likeness of the subject without offending the customer.

[217] The play was written in verse and heavily inspired by the works of Lord Byron;[218] John Pierpont considered it too dense and wrote to Neal that it needed "a sky-light or two" cut into it.

'"[95] The magazine's greatest impact on literature was uplifting new voices like John Greenleaf Whittier, Edgar Allan Poe, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Elizabeth Oakes Smith, and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Traveling on the lyceum movement circuit, he covered topics such as "literature, eloquence, the fine arts, political economy, temperance, poets and poetry, public-speaking, our pilgrim-fathers, colonization, law and lawyers, the study of languages, natural-history, phrenology, women's-rights, self-education, self-reliance, and self-distrust, progress of opinion, &c., &c., &c.".

[251] As a male writer insulated from many forms of attack leveled against earlier female feminist thinkers, Neal's advocacy was crucial to bringing the field back into published discourse in the US and UK after a lull at the turn of the century.

[269] Looking back more than forty years later, the second volume of the History of Woman Suffrage (1887) remembered that the lecture "roused considerable discussion ..., was extensively copied, and ... had a wide, silent influence, preparing the way for action.

[275] Neal was "resolutely and heartily opposed to slavery",[276] interpreting the ideals of the Declaration of Independence to mean that "the slaves in America were created free ... Ergo—They may abolish the government, which, by keeping them as they are kept, has 'violated its trust.

[281] Neal supported the American Colonization Society,[282] founding the Portland, Maine local chapter in 1833, serving as its secretary, and later meeting with Liberia's first president, Joseph Jenkins Roberts.

"[290] This led him to a proto-eugenicist argument for legalizing interracial marriage so that future generations of "the negroes of America would no longer be a separate, inferior class, without political power, without privilege, and without a share in the great commonwealth".

"[325] American literature scholar Alexander Cowie referred to Neal as "the victim of his own lust for words" with "no single work of fiction which deserves to be revived for its sheer merit"[326] and no books "worth placing on the shelves of any library save as a 'believe it or not' specimen".

[331] Many scholars conclude that most defining authors of the mid-nineteenth-century American renaissance earned their reputations by employing techniques learned from Neal's work earlier in the century, among them Ralph Waldo Emerson, Walt Whitman, Edgar Allan Poe, and Herman Melville.

"[336] American literature scholars Edward Watts, David J. Carlson, and Maya Merlob contended that Neal was written out of the Renaissance because of his distance from the Boston–Concord circle and his utilization of popular styles and modes viewed at a lower artistic level.