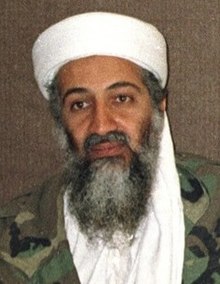

Bin Laden Issue Station

Scheuer had noticed an increase in activity by Bin Laden in Afghanistan and the rise of a new organization known as al-Qaeda, and suggested this be the focus of the station's work.

Soon after its creation, the Station developed a deadly vision of bin Laden's activities and its work came to include the planning of search and destroy missions.

In 2000, a joint CIA-USAF project using Predator reconnaissance drones and following a program drawn up by the bin Laden Station produced probable sightings of the al-Qaeda leader in Afghanistan.

Scheuer, who "had noticed a recent stream of reports about Bin Laden and something called al Qaeda", suggested that the new unit "focus on this one individual"; Cohen agreed.

[3] By 1999, the unit's staff had nicknamed themselves the "Manson Family", "because they had acquired a reputation for crazed alarmism about the rising al-Qaeda threat".

[1] The Station originally had twelve professional staff members, including CIA analyst Alfreda Frances Bikowsky and former FBI agent Daniel Coleman.

)[1]: 319, 456 [2]: 109, 479, n.2 CIA chief George Tenet later described the Station's mission as "to track [bin Laden], collect intelligence on him, run operations against him, disrupt his finances, and warn policymakers about his activities and intentions".

In May 1996, Jamal Ahmed al-Fadl walked into a US embassy in Africa and established his credentials as a former senior employee of bin Laden.

Al-Khifa was the interface of Operation Cyclone, the American effort to support the mujaheddin, and the Peshawar, Pakistan-based Services Office of Abdullah Azzam and Osama bin Laden, whose purpose was to raise recruits for the struggle against the Soviets in Afghanistan.

[2]: 62 Al-Fadl was persuaded to come to the United States by Jack Cloonan, an FBI special agent who had been seconded to the bin Laden Issue Station.

There, from late 1996, under the protection of Cloonan and his colleagues, al-Fadl "provided a major breakthrough on the creation, character, direction and intentions of al Qaeda".

"Bin Laden, the CIA now learned, had planned multiple terrorist operations and aspired to more"—including the acquisition of weapons-grade uranium.

Thousands more joined allied militias such as the [Afghan] Taliban or the Chechen rebel groups or Abu Sayyaf in the Philippines or the Islamic movement of Uzbekistan.

CTC chief Jeff O'Connell then "approved a plan to transfer the Afghans agent teams from the [CIA's] Kasi cell to the bin Laden unit".

By autumn 1997, the Station had roughed out a plan for TRODPINT to capture bin Laden and hand him over for trial, either to the US or an Arab country.

In early 1998 the Cabinet-level Principals Committee apparently gave their blessing, but the scheme was abandoned in the spring for fear of collateral fatalities during a capture attempt.

"[1]: 451–2, 455–6 [2]: 14, 142, 204 The CTC produced a "comprehensive plan of attack" against bin Laden and "previewed the new strategy to senior CIA management by the end of July 1999.

[1]: 457 Black also arranged for a CIA team, headed by Alec Station chief Blee, to visit Northern Alliance leader Ahmad Shah Massoud to discuss operations against bin Laden.

This cell met daily, brought focus to penetrating the Afghan sanctuary, and ensured that collection initiatives were synchronized with operational plans.

"[5]: 17 Beginning in September 1999, the CTC picked up multiple signs that bin Laden had set in motion major terrorist attacks for the turn of the year.

The CIA set in motion the "largest collection and disruption activity in the history of mankind", as Cofer Black later put it.

[1]: 495–6 [2]: 174–80 Amid this activity, in November and December 1999, Mohamed Atta, Marwan al-Shehhi, Ziad Jarrah and Nawaf al-Hazmi visited Afghanistan, where they were selected for the "planes operation" that was to become known as 9/11.

Atta, al-Shehhi and Jarrah met Muhammad Atef and bin Laden in Kandahar, and were instructed to go to Germany to undertake pilot training.

[12] According to Richard A. Clarke, National Coordinator for Security, Infrastructure Protection, and Counter-terrorism (counter-terrorism chief) 1998-2003, the decision to withhold from the FBI and from the White House the information that Khalid al-Mihdhar and Nawaf Al Hazmi, two Saudi Arabian nationals known at the time of their entry in 2000 into the United States to be associated with al-Qaeda, were living under their own names in Southern California, was made at the highest level of the CIA.

According to Clarke, Director of CIA George Tenet called him at the White House several times a day and met with him in person every other day to discuss "in microscopic detail" intelligence about Al-Qaeda, yet Tenet never shared this important information about the entry into the U.S. and American whereabouts of these two Al-Qaeda operatives, who on 9/11 went on to participate in the hijacking of American Airlines Flight 77.

In the summer, "The bin Laden unit drew up maps and plans for fifteen Predator flights, each lasting just under twenty-four hours."

In the summer the CIA "conducted classified war games at Langley ... to see how its chain of command might responsibly oversee a flying robot that could shoot missiles at suspected terrorists"; a series of live-fire tests in the Nevada desert (involving a mockup of bin Laden's Tarnak residence) produced mixed results.

If the Cabinet wanted to empower the CIA to field a lethal drone, Tenet said, "they should do so with their eyes wide open, fully aware of the potential fallout if there were a controversial or mistaken strike".

[18] Bin Laden was eventually located in Abbottabad, Pakistan and killed by the United States Naval Special Warfare Development Group, commonly known as SEAL Team 6 in Operation Neptune Spear on May 2, 2011.