Binary decision diagram

In computer science, a binary decision diagram (BDD) or branching program is a data structure that is used to represent a Boolean function.

On a more abstract level, BDDs can be considered as a compressed representation of sets or relations.

Similar data structures include negation normal form (NNF), Zhegalkin polynomials, and propositional directed acyclic graphs (PDAG).

to a low (or high) child represents an assignment of the value FALSE (or TRUE, respectively) to variable

A BDD is said to be 'reduced' if the following two rules have been applied to its graph: In popular usage, the term BDD almost always refers to Reduced Ordered Binary Decision Diagram (ROBDD in the literature, used when the ordering and reduction aspects need to be emphasized).

The advantage of an ROBDD is that it is canonical (unique up to isomorphism) for a particular function and variable order.

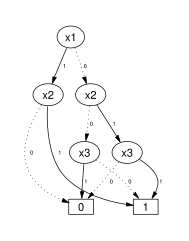

The left figure below shows a binary decision tree (the reduction rules are not applied), and a truth table, each representing the function

In the tree on the left, the value of the function can be determined for a given variable assignment by following a path down the graph to a terminal.

High edges are not complemented, in order to ensure that the resulting BDD representation is a canonical form.

To find the value of the Boolean function for a given assignment of (Boolean) values to the variables, we start at the reference edge, which points to the BDD's root, and follow the path that is defined by the given variable values (following a low edge if the variable that labels a node equals FALSE, and following the high edge if the variable that labels a node equals TRUE), until we reach the leaf node.

If when we reach the leaf node we have crossed an odd number of complemented edges, then the value of the Boolean function for the given variable assignment is FALSE, otherwise (if we have crossed an even number of complemented edges), then the value of the Boolean function for the given variable assignment is TRUE.

A switching function is split into two sub-functions (cofactors) by assigning one variable (cf.

Binary decision diagrams (BDDs) were introduced by C. Y. Lee,[6] and further studied and made known by Sheldon B. Akers[7] and Raymond T.

[8] Independently of these authors, a BDD under the name "canonical bracket form" was realized Yu.

[9] The full potential for efficient algorithms based on the data structure was investigated by Randal Bryant at Carnegie Mellon University: his key extensions were to use a fixed variable ordering (for canonical representation) and shared sub-graphs (for compression).

Applying these two concepts results in an efficient data structure and algorithms for the representation of sets and relations.

In his video lecture Fun With Binary Decision Diagrams (BDDs),[12] Donald Knuth calls BDDs "one of the only really fundamental data structures that came out in the last twenty-five years" and mentions that Bryant's 1986 paper was for some time one of the most-cited papers in computer science.

Adnan Darwiche and his collaborators have shown that BDDs are one of several normal forms for Boolean functions, each induced by a different combination of requirements.

BDDs are extensively used in CAD software to synthesize circuits (logic synthesis) and in formal verification.

There are several lesser known applications of BDD, including fault tree analysis, Bayesian reasoning, product configuration, and private information retrieval.

It is not so simple to convert from an arbitrary network of logic gates to a BDD[citation needed] (unlike the and-inverter graph).

[15] The size of the BDD is determined both by the function being represented and by the chosen ordering of the variables.

for which depending upon the ordering of the variables we would end up getting a graph whose number of nodes would be linear (in n) at best and exponential at worst (e.g., a ripple carry adder).

It is of crucial importance to care about variable ordering when applying this data structure in practice.

[16] For any constant c > 1 it is even NP-hard to compute a variable ordering resulting in an OBDD with a size that is at most c times larger than an optimal one.

[19] (If the multiplication function had polynomial-size OBDDs, it would show that integer factorization is in P/poly, which is not known to be true.

Many logical operations on BDDs can be implemented by polynomial-time graph manipulation algorithms:[21]: 20 However, repeating these operations several times, for example forming the conjunction or disjunction of a set of BDDs, may in the worst case result in an exponentially big BDD.

Computing existential abstraction over multiple variables of reduced BDDs is NP-complete.

[22] Model-counting, counting the number of satisfying assignments of a Boolean formula, can be done in polynomial time for BDDs.

For general propositional formulas the problem is ♯P-complete and the best known algorithms require an exponential time in the worst case.