Binet-Simon Intelligence Test

[3] The Binet-Simon was popular because psychologists and psychiatrists at the time felt that the test was able to measure higher and more complex mental functions in situations that closely resembled real life.

[3] This was in contrast to previous attempts at tests of intelligence, which were designed to measure specific and separate "faculties" of the mind.

[2][3][6] Galton and Cattell discontinued their research when they realised that their measurements of human bodies did not correlate to academic performance.

[6] Before working on the test, Alfred Binet had experience of raising his two daughters on whom he also conducted studies of intelligence between 1900 and 1902.

[3][4] He had already written a considerable number of scientific articles on individual differences, intelligence, magnetism, hypnosis, and many other psychological topics.

Binet and Simon started working together, first looking at the relationship between skull measurements and intelligence, and later abandoning this anthropometric approach in favour of psychological testing.

These children, referred to as feebleminded or mentally retarded, supposedly caused trouble in French primary schools because they were unable to follow standard education and were disturbing the rest of their classmates.

[3][4] The Bourgeois Commission was staffed by specialists in the study of children with mental abnormality (psychiatrists, psychologists), members of the public education system and representatives from the interior ministry.

[4] Binet joined the Commission because of his presidency of La Société libre pour l'étude psychologique de l'enfant (Free Society of the Psychological Study of the Child).

La Société libre pour l'étude psychologique de l'enfant was a scientific collaboration mainly between scientists and educators.

[4] Identifying and treating the abnormal had, until that point, been a psychiatric domain but Binet wanted to keep these children in schools and looked for a way for psychologists to become the authority.

[4] Binet was supported in this attempt by La Société libre pour l'étude psychologique de l'enfant, other collaborators and friends.

La Société libre pour l'étude psychologique de l'enfant lobbied against both these plans, and Binet was encouraged to come up with a better alternative to measure the difference between normal and abnormal children.

[4] The measurement of basic skills included tasks such as object grabbing and testing knowledge of food.

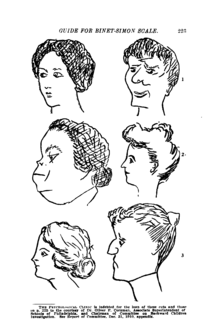

The distinction between idiocy and imbecility was made by for example testing verbal knowledge of objects and images and comparing two lines of different lengths.

Lastly, to differentiate between debility and normality, a child could be asked to respond to an abstract question or to perform a paper cutting exercise.

Binet and Simon saw a two or more years lag as a warning sign of low intelligence, which required special attention, first by providing remedial education.

[5] This 1911 publication was made up mainly of clarifications and reactions to comments from teachers and researchers and the presentation of new data collected from using the test in a couple of schools.

This English version included a category for idiocy (questions 1–6), which measures a mental age of 1–2, and the addition of tests 17a and 50a.

[12] Moreover, Binet and Simon presented evidence that the order of tasks was linear and that a child's score on the test would correlate to their academic performance.

'[3] The test's original purpose was to distinguish between normal and abnormal children in French primary schools.

[10] In Stephen Jay Gould's book 'the mismeasure of man', Gould argues that even though the Binet-Simon test was used for a morally good goal (to identify children who needed extra help), the way the test was subsequently used in the United States by psychologists such as Spearman, Terman, Goddard, Burt and Brigham, was not ethical.

[3] The test has built-in sets of norms and values that assume the kind of mental work a normal citizen should be able to perform.

Shortly after, other famous pedagogues and psychologists such as Édouard Claparède and Ovide Decroly, joined him in his advocacy of the test.

[3][9] By using their large and far-reaching network, information about the Binet-Simon test's reliability and efficiency spread rapidly during the period when schooling became public and graded.

[3] A group of physicians from Barcelona hired by the City Hall were among the first to use a translated version of the 1908 version.They tested 420 boys and girls to identify physically, mentally, and socially lagging schoolchildren.

[9][12] In 1916, Goddard instructed his laboratory field worker, Elizabeth S. Kite, to translate the complete Binet and Simon's work on the intelligence test into English.

[9] As the head of research at Vineland Training School for Feeble-minded Girls and Boys, Goddard led a movement that would result in the widespread use of the Binet-Simon test in American Institutions.