Binomial coefficient

in successive rows for n = 0, 1, 2, ... gives a triangular array called Pascal's triangle, satisfying the recurrence relation The binomial coefficients occur in many areas of mathematics, and especially in combinatorics.

In about 1150, the Indian mathematician Bhaskaracharya gave an exposition of binomial coefficients in his book Līlāvatī.

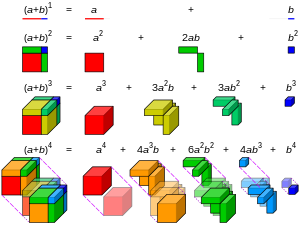

This number can be seen as equal to the one of the first definition, independently of any of the formulas below to compute it: if in each of the n factors of the power (1 + X)n one temporarily labels the term X with an index i (running from 1 to n), then each subset of k indices gives after expansion a contribution Xk, and the coefficient of that monomial in the result will be the number of such subsets.

This recursive formula then allows the construction of Pascal's triangle, surrounded by white spaces where the zeros, or the trivial coefficients, would be.

The denominator counts the number of distinct sequences that define the same k-combination when order is disregarded.

Due to the symmetry of the binomial coefficients with regard to k and n − k, calculation of the above product, as well as the recursive relation, may be optimised by setting its upper limit to the smaller of k and n − k. Finally, though computationally unsuitable, there is the compact form, often used in proofs and derivations, which makes repeated use of the familiar factorial function:

It is less practical for explicit computation (in the case that k is small and n is large) unless common factors are first cancelled (in particular since factorial values grow very rapidly).

The multiplicative formula allows the definition of binomial coefficients to be extended[4] by replacing n by an arbitrary number α (negative, real, complex) or even an element of any commutative ring in which all positive integers are invertible:

If α is a nonnegative integer n, then all terms with k > n are zero,[5] and the infinite series becomes a finite sum, thereby recovering the binomial formula.

However, for other values of α, including negative integers and rational numbers, the series is really infinite.

For instance, by looking at row number 5 of the triangle, one can quickly read off that Binomial coefficients are of importance in combinatorics because they provide ready formulas for certain frequent counting problems: For any nonnegative integer k, the expression

As such, it can be evaluated at any real or complex number t to define binomial coefficients with such first arguments.

The integer-valued polynomial 3t(3t + 1) / 2 can be rewritten as The factorial formula facilitates relating nearby binomial coefficients.

For instance, if k is a positive integer and n is arbitrary, then and, with a little more work, We can also get Moreover, the following may be useful: For constant n, we have the following recurrence: To sum up, we have The formula says that the elements in the nth row of Pascal's triangle always add up to 2 raised to the nth power.

However, these subsets can also be generated by successively choosing or excluding each element 1, ..., n; the n independent binary choices (bit-strings) allow a total of

The Chu–Vandermonde identity, which holds for any complex values m and n and any non-negative integer k, is and can be found by examination of the coefficient of

In the special case n = 2m, k = m, using (1), the expansion (7) becomes (as seen in Pascal's triangle at right) where the term on the right side is a central binomial coefficient.

When j = k, equation (9) gives the hockey-stick identity and its relative Let F(n) denote the n-th Fibonacci number.

series multisection gives the following identity for the sum of binomial coefficients: For small s, these series have particularly nice forms; for example,[8] Although there is no closed formula for partial sums of binomial coefficients,[9] one can again use (3) and induction to show that for k = 0, …, n − 1, with special case[10] for n > 0.

[12] One may show by induction that F(n) counts the number of ways that a n × 1 strip of squares may be covered by 2 × 1 and 1 × 1 tiles.

ways to order these tiles, and so summing this coefficient over all possible values of k gives the identity.

, where each digit position is an item from the set of n. Dixon's identity is or, more generally, where a, b, and c are non-negative integers.

A symmetric exponential bivariate generating function of the binomial coefficients is: In 1852, Kummer proved that if m and n are nonnegative integers and p is a prime number, then the largest power of p dividing

equals pc, where c is the number of carries when m and n are added in base p. Equivalently, the exponent of a prime p in

Binomial coefficients have divisibility properties related to least common multiples of consecutive integers.

If n is large and k is linear in n, various precise asymptotic estimates exist for the binomial coefficient

[18] The infinite product formula for the gamma function also gives an expression for binomial coefficients

The product of all binomial coefficients in the nth row of the Pascal triangle is given by the formula: The partial fraction decomposition of the reciprocal is given by Newton's binomial series, named after Sir Isaac Newton, is a generalization of the binomial theorem to infinite series: The identity can be obtained by showing that both sides satisfy the differential equation (1 + z) f'(z) = α f(z).

The behavior is quite complex, and markedly different in various octants (that is, with respect to the x and y axes and the line

One can show that the generalized binomial coefficient is well-defined, in the sense that no matter what set we choose to represent the cardinal number