Taylor's theorem

[3] Taylor's theorem is taught in introductory-level calculus courses and is one of the central elementary tools in mathematical analysis.

It provided the mathematical basis for some landmark early computing machines: Charles Babbage's Difference Engine calculated sines, cosines, logarithms, and other transcendental functions by numerically integrating the first 7 terms of their Taylor series.

Taylor's theorem ensures that the quadratic approximation is, in a sufficiently small neighborhood of

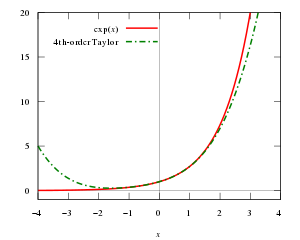

Similarly, we might get still better approximations to f if we use polynomials of higher degree, since then we can match even more derivatives with f at the selected base point.

However, there are functions, even infinitely differentiable ones, for which increasing the degree of the approximating polynomial does not increase the accuracy of approximation: we say such a function fails to be analytic at x = a: it is not (locally) determined by its derivatives at this point.

It does not tell us how large the error is in any concrete neighborhood of the center of expansion, but for this purpose there are explicit formulas for the remainder term (given below) which are valid under some additional regularity assumptions on f. These enhanced versions of Taylor's theorem typically lead to uniform estimates for the approximation error in a small neighborhood of the center of expansion, but the estimates do not necessarily hold for neighborhoods which are too large, even if the function f is analytic.

In that situation one may have to select several Taylor polynomials with different centers of expansion to have reliable Taylor-approximations of the original function (see animation on the right.)

There are several ways we might use the remainder term: The precise statement of the most basic version of Taylor's theorem is as follows: Taylor's theorem[4][5][6] — Let k ≥ 1 be an integer and let the function f : R → R be k times differentiable at the point a ∈ R. Then there exists a function hk : R → R such that

Under stronger regularity assumptions on f there are several precise formulas for the remainder term Rk of the Taylor polynomial, the most common ones being the following.

However, it holds also in the sense of Riemann integral provided the (k + 1)th derivative of f is continuous on the closed interval [a,x].

, its derivative f(k+1) exists as an L1-function, and the result can be proven by a formal calculation using the fundamental theorem of calculus and integration by parts.

It is often useful in practice to be able to estimate the remainder term appearing in the Taylor approximation, rather than having an exact formula for it.

By definition, a function f : I → R is real analytic if it is locally defined by a convergent power series.

Here only the convergence of the power series is considered, and it might well be that (a − R,a + R) extends beyond the domain I of f. The Taylor polynomials of the real analytic function f at a are simply the finite truncations

by the tail of the sequence of the derivatives f′(a) at the center of the expansion, but using complex analysis also another possibility arises, which is described below.

The Taylor series of f will converge in some interval in which all its derivatives are bounded and do not grow too fast as k goes to infinity.

Now the estimates for the remainder imply that if, for any r, the derivatives of f are known to be bounded over (a − r, a + r), then for any order k and for any r > 0 there exists a constant Mk,r > 0 such that for every x ∈ (a − r,a + r).

Using the chain rule repeatedly by mathematical induction, one shows that for any order k,

, so f is infinitely many times differentiable and f(k)(0) = 0 for every positive integer k. The above results all hold in this case: However, as k increases for fixed r, the value of Mk,r grows more quickly than rk, and the error does not go to zero.

Namely, stronger versions of related results can be deduced for complex differentiable functions f : U → C using Cauchy's integral formula as follows.

Then Cauchy's integral formula with a positive parametrization γ(t) = z + reit of the circle S(z, r) with

Here all the integrands are continuous on the circle S(z, r), which justifies differentiation under the integral sign.

All that is said for real analytic functions here holds also for complex analytic functions with the open interval I replaced by an open subset U ∈ C and a-centered intervals (a − r, a + r) replaced by c-centered disks B(c, r).

Methods of complex analysis provide some powerful results regarding Taylor expansions.

For example, using Cauchy's integral formula for any positively oriented Jordan curve

, one obtains expressions for the derivatives f(j)(c) as above, and modifying slightly the computation for Tf(z) = f(z), one arrives at the exact formula

This kind of behavior is easily understood in the framework of complex analysis.

In this case, due to the continuity of (k+1)-th order partial derivatives in the compact set B, one immediately obtains the uniform estimates

but the requirements for f needed for the use of mean value theorem are too strong, if one aims to prove the claim in the case that f(k) is only absolutely continuous.

The strategy of the proof is to apply the one-variable case of Taylor's theorem to the restriction of