Biological ornament

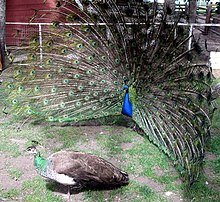

An animal may shake, lengthen, or spread out its ornament in order to get the attention of the opposite sex, which will in turn choose the most attractive one with which to mate.

These structures serve as cues to animal sexual behaviour, that is, they are sensory signals that affect mating responses.

Darwin was the first to correctly hypothesize that sexual selection by female choice was responsible for the evolution of elaborate plumage and remarkable displays in male birds such as the quetzal and the sage grouse.

[3] In his 1871 book The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, Darwin was perplexed by the elaborate ornamentation that males of some species have because they appeared to be detrimental to survival and have negative consequences for reproductive success.

Since disease is a major source of juvenile mortality, females would choose the males with the most elaborate ornaments to ensure that they will have healthy offspring.

Females may improve survival of offspring by selecting mates on the basis of ornamentation signals that honestly reveal health.

Numerous studies have been carried out to test if sexual selection based on the intensity of the expression of ornamentation in males reflects their level of oxidative stress.

[9][10] It is considered that female choice may select for traits in males that reliably indicate level of oxidative stress, as such traits would be a good indicator of male quality[9][10] Elevated oxidative stress can lead to increased DNA damage that can contribute to aging or cancer.

Female choice thus may promote the evolution of ornaments in males that reliably reveal the level of oxidative stress in potential mating partners.

Male quetzals have iridescent green wing coverts, back, chest and head, and a red belly.

During mating season, male quetzals grow twin tail feathers that form an amazing train up to three feet long (one meter) with vibrant colors.

Coloration and tail feather length in quetzals help determine mate choice because the females choose the more elaborately ornamented males.

These weapons such as tusks, antlers, horns, spurs, and lips increase success in rivalry among competitors to gain or maintain dominance, control a harem, or obtain access to territories Examples of animals that use armaments to compete in battle against rival males include deer and antelope; scarabid, lucanid, and cerambycid beetles; certain fish, and narwhales.

[18] Important studies concerning this have been conducted in the Stalk-eyed fly, showing that females are attracted to mates that share characteristics with their fathers.

This evolution can then lead to organs of excessive size that may become troublesome for the males, such as large, bushy tails, bright feathers, etc.

[18] Sexually selected ornaments of males may impose survival costs but advance success in the competition for mates.

[22] For example, baby American coots hatch out with long, orange-tipped plumes on their backs and throats which provide signals to parents used to determine which individuals to feed preferentially.

[24] Female traits in empidids, such as abdominal sacs and enlarged pinnate leg scales, have been suggested to 'deceive' males into matings by disguising egg maturity.