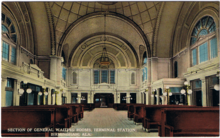

Birmingham Terminal Station

They funded a new $2 million terminal station covering two blocks of the city at the eastern end of 5th Avenue North downtown.

Celebrations included a balloon race, a parade led by Grand Marshal E. J. McCrossin, and a banquet for city officials at the Hillman Hotel.

[citation needed] In 2015, Rhea Williams, executive director of American Institute of Architects Birmingham expressed regret over the demolition of the train station.

Local Civil Rights leaders like Fred Shuttlesworth challenged the racially segregated accommodations of the station and crowds of belligerent whites gathered, sometimes leading to violence.

[citation needed] The station was constructed with separate waiting areas to comply with segregation laws mandated by the Jim Crow provisions in the state's 1901 constitution.

However, this ruling created a distinction between interstate and intrastate travelers, prompting a legal case in 1957 to desegregate the waiting areas.

[1] In 1957, Fred Shuttlesworth staged a protest by entering the white waiting room at Terminal Station with his wife, Ruby, before boarding a train.

During the event, Lamar Weaver, a white supporter of integration who had come to speak with Shuttlesworth, was attacked by members of the crowd as he returned to his vehicle.

Historian Marvin Clemons said the station had outlived its usefulness, with railroads seeking to recover losses from declining passenger service due to the rise in private automobile usage.

[2] An underpass, locally called a "subway" tunneled below the center of the building, allowing streetcars to bypass the terminal and rail traffic.

In 1926 a large electric sign reading "Welcome to Birmingham, the Magic City", was erected outside the station at the west end of the underpass.

The sign functioned as a gateway for visitors who arrived primarily by rail and 5th Avenue became a "hotel row", lined with restaurants and entertainments.