Anniston and Birmingham bus attacks

To challenge this, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) organized for an interracial group of volunteers – whom they dubbed "Freedom Riders" – to travel together through the Deep South, hoping to provoke a violent reaction from segregationists that would force the federal government to step in.

Traveling in two groups on Greyhound and Trailways bus lines, they would pass through the segregationist stronghold of Alabama, where Birmingham Police Commissioner Eugene "Bull" Connor conspired with local chapters of the Klan to attack the Riders.

They continued to Birmingham, where a mob of additional Klan members, armed with blunt weapons, attacked the Freedom Riders in a fifteen minute frenzy of violence, during which the area was deliberately vacated by the police.

By orchestrating them, Connor and the Klan had intended to deter future Rides, but they had the opposite effect and inspired hundreds of volunteers to spend the summer of 1961 traveling across the South facing arrest and mob violence.

[15] Intending to test how the 1946 Supreme Court ruling was being enforced in the Upper South, FOR member Bayard Rustin organized what he called a "Journey of Reconciliation" – now sometimes referred to as the "First Freedom Ride".

However, twelve were arrested for violating segregation and four – Rustin, Igal Roodenko, Joe Felmet, and Andrew Johnson – were sentenced to serve in chain gangs for periods ranging from 30–90 days.

In 1960, a second Supreme Court ruling, Boynton v. Virginia, extended the ban on segregation on interstate public buses to include the associated terminals and facilities, such as waiting rooms, lunch counters, and restrooms.

After Martin Luther King Jr. was refused an invitation to a meeting between Kennedy and other civil rights leaders, he and James Farmer agreed that action needed to be taken in order to force the federal government to act.

He raised the issue at a CORE meeting, where Tom Gaither and Gordon Carey – who had been reading The Life of Mahatma Gandhi by Louis Fischer and was inspired by the Salt March – announced that they had been considering a revival of the 1947 Journey of Reconciliation.

The SNCC approved a "Summer Action Program", which would involve encouraging black college students to exercise the rights given to them in Morgan and Boynton as they traveled home across the country at the end of the school term.

News of the plan elicited a mixed reaction but Gaither still successfully convinced dozens of organizations (ranging from Baptist congregations to private black colleges) to host the Riders and provide speaking engagements.

[17][20] That night, while staying at Rock Hill's Friendship Junior College, Lewis received a telegram from the AFSC informing him that he was a finalist for a coveted foreign service internship.

It was rife with racial tension, and had already been the site of violence on January 2, when Talladega College student Art Bacon was viciously beaten after he sat in a whites-only waiting room at the city's railway station.

In addition to seven Riders – Bigelow, Blankenheim, Hughes, McDonald, Moultrie, Perkins (team leader), and Thomas – and two journalists – Devree and Newson – the bus was also carrying five regular passengers.

Unbeknownst to the Riders, among them were Roy Robinson, manager of the Atlanta Greyhound station, and two plainclothes agents of the Alabama Highway Patrol, Ell Cowling and Harry Sims.

In addition to the Klansmen, the commotion had attracted a number of local residents and journalists; somewhere between thirty and fifty vehicles (possibly carrying up to two hundred people) were in pursuit of the bus when it stopped.

While some passengers started climbing out of broken windows, others attempted to get out the front entrance, but Klansmen – screaming taunts such as "Burn them alive" and "Fry the goddamn niggers" – held it shut.

Eventually, the mob was forced back (sources differ on whether this was due to an exploding fuel tank or the threat of Cowling's gun) and the remaining Riders were able to exit the bus.

[3][5][6][9] The Klansmen were permanently forced back to a firm perimeter after Cowling and the other Highway Patrol agents fired a number of warning shots, signalling that a mass lynching was out of the question.

Perkins placed frantic calls to CORE contacts in D.C. and was put in touch with Shuttlesworth, who organized for several cars of local black activists to launch a rescue mission.

Led by Colonel Stone Johnson and openly armed with shotguns, the activists held back the mob of Klansmen as the Riders were shuffled from the hospital into the rescue cars.

[3] Back in Atlanta, the departure of the Greyhound group had left the remaining Freedom Riders – the Bergmans, Harris, Moore, Peck (team leader), Person, and Reynolds – and the other two journalists – Booker and Gaffney – to board a Trailways bus for the next leg next of the trip to Birmingham.

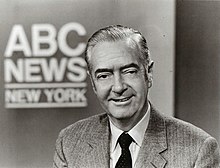

Among them were Howard K. Smith of CBS News, who received a phone call the night before from Edward Reed Fields, president of the white supremacist National States' Rights Party (NSRP).

The attack was witnessed by Tommy Langston of the Birmingham Post-Herald, who snapped a photograph with his flashbulb camera, seen below:[3] The flash diverted the mob's attention away from Webb, who was able to reunite with Spicer and escape.

[5][7][35][36] Smith's eyewitness account of the Birmingham mob violence was broadcast on CBS, while photographs of the burning Greyhound bus and Langston's shot of the attack on Webb were published nationwide in newspapers.

Shuttlesworth was amazed when local reporters he considered to be pro-segregation published critical accounts of the attacks; the front page of The Birmingham News was headlined "People Are Asking: 'Where Were The Police?'"

[6] After receiving medical treatment, the Freedom Riders and the accompanying journalists were eventually reunited at Shuttlesworth's house, which doubled as a headquarters for the Alabama Christian Movement for Human Rights.

Due to the threat of more violence and the fact that they could not find a bus driver willing to drive them, the Riders were eventually convinced by Kennedy to take a plane to New Orleans, where they would attend the planned civil rights rally.

[6][35] Meanwhile, in Nashville, Tennessee, SNCC cofounder Diane Nash firmly believed that if the Freedom Ride was halted, it would send a message that violence could stop the civil rights movement.

Police abandoned the bus as it reached the city limits and when the Riders disembarked at the terminal, they were beaten by a large mob of whites in circumstances that were almost identical to the attack in Birmingham.