Salt March

The Dandi March and the ensuing Dharasana Satyagraha drew worldwide attention to the Indian independence movement through extensive newspaper and newsreel coverage.

The satyagraha against the salt tax continued for almost a year, ending with Gandhi's release from jail and negotiations with Viceroy Lord Irwin at the Second Round Table Conference.

The Salt March to Dandi, and the beating by the colonial police of hundreds of nonviolent protesters in Dharasana, which received worldwide news coverage, demonstrated the effective use of civil disobedience as a technique for fighting against social and political injustice.

[8] The march was the most significant organised challenge to British authority since the Non-cooperation movement of 1920–22, and directly followed the Purna Swaraj declaration of sovereignty and self-rule by the Indian National Congress on 26 January 1930 by celebrating Independence Day.

The Indian National Congress, led by Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru, publicly issued the Declaration of Sovereignty and Self-rule, or Purna Swaraj, on 26 January 1930.

Initially, Gandhi's choice of the salt tax was met with incredulity by the Working Committee of the Congress,[14] Jawaharlal Nehru and Divyalochan Sahu were ambivalent; Sardar Patel suggested a land revenue boycott instead.

"[16] Gandhi had a long-standing commitment to nonviolent civil disobedience, which he termed satyagraha, as the basis for achieving Indian sovereignty and self-rule.

Even though it succeeded in raising millions of Indians in protest against the British-created Rowlatt Act, violence broke out at Chauri Chaura, where a mob killed 22 unarmed policemen.

Expectations were heightened by his repeated statements anticipating arrest, and his increasingly dramatic language as the hour approached: "We are entering upon a life and death struggle, a holy war; we are performing an all-embracing sacrifice in which we wish to offer ourselves as an oblation.

"[32] Correspondents from dozens of Indian, European, and American newspapers, along with film companies, responded to the drama and began covering the event.

For that reason, he recruited the marchers not from Congress Party members, but from the residents of his own ashram, who were trained in Gandhi's strict standards of discipline.

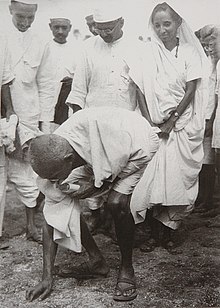

"[41][42] On 12 March 1930, Gandhi and 78 satyagrahis, among whom were men belonging to almost every region, caste, creed, and religion of India,[43] set out on foot for the coastal village of Dandi in Navsari district of Gujarat, 385 km from their starting point at Sabarmati Ashram.

Foreign journalists and three Bombay cinema companies shooting newsreel footage turned Gandhi into a household name in Europe and America (at the end of 1930, Time magazine made him "Man of the Year").

The wanton disregard shown by them to popular feeling in the Legislative Assembly and their high-handed action leave no room for doubt that the policy of heartless exploitation of India is to be persisted in at any cost, and so the only interpretation I can put upon this non-interference is that the British Government, powerful though it is, is sensitive to world opinion which will not tolerate repression of extreme political agitation which civil disobedience undoubtedly is, so long as disobedience remains civil and therefore necessarily non-violent ....

Appealing for violence to end, at the same time Gandhi honoured those killed in Chittagong and congratulated their parents "for the finished sacrifices of their sons ... A warrior's death is never a matter for sorrow.

The attempted suppression of the movement was presided over by MacDonald and his cabinet (including the Secretary of State for India, William Wedgwood Benn).

[65] During this period, the MacDonald ministry also oversaw the suppression of the nascent trade unionist movement in India, which was described by historian Sumit Sarkar as "a massive capitalist and government counter-offensive" against workers' rights.

[66] In Peshawar, satyagraha was led by a Muslim Pashtun disciple of Gandhi, Ghaffar Khan, who had trained 50,000 nonviolent activists called Khudai Khidmatgar.

The 2/18 battalion of the Royal Garhwal Rifles were ordered to open fire with machine guns on the unarmed crowd, killing an estimated 200–250 people.

[69] One British Indian Army soldier, Chandra Singh Garhwali and some other troops from the renowned Royal Garhwal Rifles regiment refused to fire at the crowds.

A government report on the involvement of women stated "thousands of them emerged ... from the seclusion of their homes ... in order to join Congress demonstrations and assist in picketing: and their presence on these occasions made the work the police was required to perform particularly unpleasant.

John Court Curry, an Indian Imperial Police officer from England, wrote in his memoirs that he felt nausea every time he dealt with Congress demonstrations in 1930.

Curry and others in British government, including Wedgwood Benn, Secretary of State for India, preferred fighting violent rather than nonviolent opponents.

Around midnight of 4 May, as Gandhi was sleeping on a cot in a mango grove, the District magistrate of Surat drove up with two Indian officers and thirty heavily armed constables.

[76] The Dharasana Satyagraha went ahead as planned, with Abbas Tyabji, a seventy-six-year-old retired judge, leading the march with Gandhi's wife Kasturba at his side.

After their arrests, the march continued under the leadership of Sarojini Naidu, a woman poet and freedom fighter, who warned the satyagrahis, "You must not use any violence under any circumstances.

[78]Vithalbhai Patel, former Speaker of the Assembly, watched the beatings and remarked, "All hope of reconciling India with the British Empire is lost forever.

The Salt Satyagraha did not produce immediate progress toward dominion status or self-rule for India, did not elicit major policy concessions from the British,[83] or attract much Muslim support.

But the real importance, to my mind, lay in the effect they had on our own people, and especially the village masses ... Non-cooperation dragged them out of the mire and gave them self-respect and self-reliance ...

As I delved deeper into the philosophy of Gandhi, my skepticism concerning the power of love gradually diminished, and I came to see for the first time its potency in the area of social reform.