Black Death in Sweden

In the public royal letter, which was circulated to the Bishops of the Kingdom, all Swedes regardless of class, age or gender were commanded to regularly attend mass, give alms to the poor, confess and do penance, fast on water and bread every Friday and give what they could to the Virgin Mary, the church and the king.

[1] The Black Death first appeared in Sweden in the big port city of Visby on Gotland, likely by ship from Denmark or Germany, where it was present in May or at the latest July 1350.

[2] The Black Death appears to have first reached Gotland by sea in the spring or early summer of 1350, and spread across Eastern and Central Sweden during the summer and autumn: from Småland and Östergötland to Närke and Uppland between August and December 1350, with a presence in Stockholm and Uppsala in August.

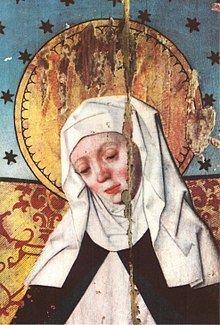

[1] Saint Bridget of Sweden commented on the Black Death in Sweden: She stated that the Black Death had reached Sweden because of the Sins of pride, intemperance and greed, particularly because of the sinful dress fashion of the women, and that the wrath of God could be placated if the Swedes abstained from sinfully provocative fashion; if the parish priests lead their congregations in penance; and if the bishops organized public penitence masses in the cathedrals and washed the feet of the poor.

In March 1351, the pope sent a letter to Sweden in Norway as a reply to this letter, in which he ordered the Bishops of Lund, Uppsala and Trondheim to encourage their parishioners to join the king in his crusade against the Orthodox Russians, because so many of his soldiers and subjects had died during the plague that he was forced to interrupt his crusade.

It is commonly assumed that the king's two stepbrothers, the sons of his mother Ingeborg of Norway and stepfather duke Canute Porse the Elder, died from the Black Death, as were many individuals who were noted to have died in 1350 or 1351, but in no case are there any contemporary documents which can verify it.

[2] The priesthood was the most well documented class from this period in Sweden, and it appears half of the parish priests in Västerås and Strängnäs may have died judging from the fact that about half of them were replaced in the years after the Black Death, but only a quarter of the canons; it is also a fact, that all of the Bishops in Sweden (with Finland) survived the Black Death.

[1] The population loss caused a crisis during which the nobility unsuccessfully attempted to introduce serfdom in the 15th century.

A donation of a property from Lady Margareta, the widow of Avid of Risnäs, and her son Stefan to the Linköping Cathedral on 13 June 1353, is a rare example of this, as the document clearly states that they had to sell the property for a much lower price than its actual worth: The higher demands of the workers and peasants and the lower incomes of the nobility caused social tensions that resulted in several local charters such as the Skara Charter of 1414 and the Växjö Charter of 1414, which attempted to introduce serfdom by forcing the tenant farmers to stay on the noble estates with heavy regulations, restricting their rights to move and raising their obligation to work on the noble estates and their taxes to the landlords; in Sweden, however, the power of the nobility and the feudal system was too weak for any serfdom to be successfully introduced, and these laws do not appear to have been effective.

[1] In the Engelbrektskrönikan ('Engelbrekt Chronicle') from the 1430s, there were complaints about the heavy taxes imposed by Eric of Pomerania with reference to the Black Death, as the king was criticized for demanding a tax which the country could no longer afford, as the population had decreased by the 'Great Death' since then, which devastated the land so that "where former one hundred farmers were, there are now but twenty".

For centuries, ruins in the forests were often explained as remains from towns and villages devastated by the "Great Death".

[1] Vadstena Abbey was not yet founded in 1350, but the Bridgettine monk Anders Lydekesson (d. 1410) nevertheless included a description of it in his chronicle from 1403 to 1408, in which he mentioned for the year of 1350: Bishop Peder Månsson of Västerås noted that many farms belonging to the Bishopric were still deserted because of the Black Death, and Olaus Petri attributed the small population of Sweden to the Black Death and referred to it as the cause to why there were wilderness and forests where there had previously been villages and farms.

King Magnus Eriksson's son and co-regent Erik Magnusson, his consort Beatrix, and their children possibly died of the plague in 1359.