Serfdom

[5] James Lee and Cameron Campbell describe the Chinese Qing dynasty (1644–1912) as also maintaining a form of serfdom.

[9][10] Bhutan is described by Tashi Wangchuk, a Bhutanese civil servant, as having officially abolished serfdom by 1959, but he believes that less than or about 10% of poor peasants were in copyhold situations.

[citation needed] During this period, powerful feudal lords encouraged the establishment of serfdom as a source of agricultural labour.

Serfdom, indeed, was an institution that reflected a fairly common practice whereby great landlords were assured that others worked to feed them and were held down, legally and economically, while doing so.

As slavery gradually disappeared and the legal status of servi became nearly identical to that of the coloni, the term changed meaning into the modern concept of "serf".

One rationale held that serfs and freemen "worked for all" while a knight or baron "fought for all" and a churchman "prayed for all"; thus everyone had a place (see Estates of the realm).

The colonus system of the late Roman Empire can be considered the predecessor of Western European feudal serfdom.

Ministeriales were hereditary unfree knights tied to their lord, that formed the lowest rung of nobility in the Holy Roman Empire.

[dubious – discuss] Villeins had more rights and higher status than the lowest serf, but existed under a number of legal restrictions that differentiated them from freemen.

[citation needed] Like other types of serfs, villeins had to provide other services, possibly in addition to paying rent of money or produce.

Villeinage, as opposed to other forms of serfdom, was most common in Continental European feudalism, where land ownership had developed from roots in Roman law.

Half-villeins received only half as many strips of land for their own use and owed a full complement of labour to the lord, often forcing them to rent out their services to other serfs to make up for this hardship.

[citation needed] In many medieval countries, a villein could gain freedom by escaping from a manor to a city or borough and living there for more than a year; but this action involved the loss of land rights and agricultural livelihood, a prohibitive price unless the landlord was especially tyrannical or conditions in the village were unusually difficult.

[22] Status-wise, the bordar or cottar ranked below a serf in the social hierarchy of a manor, holding a cottage, garden and just enough land to feed a family.

Usually, a portion of the week was devoted to ploughing his lord's fields held in demesne, harvesting crops, digging ditches, repairing fences, and often working in the manor house.

The remainder of the serf's time was spent tending his own fields, crops and animals in order to provide for his family.

On Easter Sunday the peasant family perhaps might owe an extra dozen eggs, and at Christmas, a goose was perhaps required, too.

When a family member died, extra taxes were paid to the lord as a form of feudal relief to enable the heir to keep the right to till what land he had.

Any young woman who wished to marry a serf outside of her manor was forced to pay a fee for the right to leave her lord, and in compensation for her lost labour.

It was also a matter of discussion whether serfs could be required by law in times of war or conflict to fight for their lord's land and property.

The landlord could not dispossess his serfs without legal cause and was supposed to protect them from the depredations of robbers or other lords, and he was expected to support them by charity in times of famine.

Serfs served on occasion as soldiers in the event of conflict and could earn freedom or even ennoblement for valour in combat.

[clarification needed] Serfs could purchase their freedom, be manumitted by generous owners, or flee to towns or to newly settled land where few questions were asked.

On the outbreak of the French Revolution of 1789, between 140,000[34] and 1,500,000[35] serfs remained in France, most of them on clerical lands[36] in Franche-Comté, Berry, Burgundy and Marche.

[42] In Gaelic Ireland, a political and social system existing in Ireland from the prehistoric period (500 BC or earlier) up until the Norman conquest (12th century AD), the bothach ("hut-dweller"), fuidir (perhaps linked to fot, "soil")[43] and sencléithe ("old dwelling-house")[44] were low-ranked semi-free servile tenants similar to serfs.

[45][46] According to Laurence Ginnell, the sencléithe and bothach "were not free to leave the territory except with permission, and in practice they usually served the flaith [prince].

Although his condition is servile, he retains the right to abandon his holding on giving due notice to the lord and surrendering to him two thirds of the products of his husbandry.

Over the course of the 19th century, it was gradually abolished on Polish and Lithuanian territories under foreign control, as the region began to industrialize.

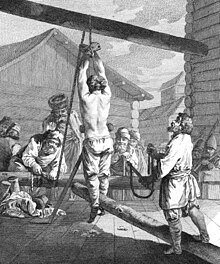

According to the Encyclopedia of Human Rights: In 1649 up to three-quarters of Muscovy's peasants, or 13 to 14 million people, were serfs whose material lives were barely distinguishable from slaves.

[51]Russia's over 23 million (about 38% of the total population[52]) privately held serfs were freed from their lords by an edict of Alexander II in 1861.