Black Hawk (Sauk leader)

During the War of 1812, Black Hawk fought on the side of the British against the US in the hope of pushing white American settlers away from Sauk territory.

He was said to be a descendant of Nanamakee (Thunder), a Sauk chief who, according to tradition, met an early French explorer, possibly Samuel de Champlain.

After Pyesa died from wounds received in the battle, Black Hawk inherited the Sauk sacred bundle which his father had carried, giving him an important role in the tribe.[4]: pp.

16–17 After an extended period of mourning for his father, Black Hawk resumed leading raiding parties over the next years, usually targeting the traditional enemy, the Osage.

[7][page range too broad] The Sauk and Fox are consensus-based decision makers and those representatives sent to the meeting with the US government did not have the power to cede tribal territory, although Quashquame did.

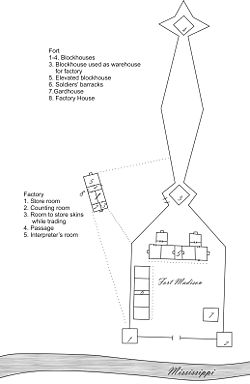

[8] Black Hawk took part in skirmishes against US forces at the newly constructed Fort Madison in the disputed land; this was the first time he fought directly against the U.S.

Robert Dickson, a Scottish fur trader, amassed a sizable force of Native Americans at Green Bay to assist the British in operations around the Great Lakes.

[citation needed] Dickson commissioned Black Hawk at the rank of brevet brigadier general,[7] with command over all native allies at Green Bay, and presented him with a silk flag, a medal, and a written certificate of good behavior and alliance with the British.

The war leader preserved the certificate for 20 years; it was found by U.S. forces after the Battle of Bad Axe, along with a flag similar in description to that which Dickson gave to Black Hawk.

[7] During the war, Black Hawk and Native warriors fought in several engagements alongside Major-General Henry Procter on the borders of Lake Erie.

[10] At the Battle of Credit Island, and by harassing U.S. troops at Fort Johnson, Black Hawk helped the British to push the Americans out of the upper Mississippi River valley.

[8] As a consequence of the 1804 treaty, the American government believed that the Sauk and Fox tribes had ceded their lands in Illinois and in 1828 were moved west of the Mississippi River.

In April 1832, encouraged by promises of alliance with other tribes and with Britain, he moved his so-called "British Band" of more than 1500 people, both warriors and non-combatants, into Illinois.

Afterward, the Illinois and Michigan Territory militias caught up with Black Hawk's "British Band" for the final confrontation at Bad Axe.

At the mouth of the Bad Axe River, pursuing soldiers, their Indian allies, and a U.S. gunboat killed hundreds of Sauk and Potawatomi men, women and children.

[26][27][28][29] Following the war, with most of the British Band killed and the rest captured or disbanded, the defeated Black Hawk was held in captivity at Jefferson Barracks near Saint Louis, Missouri together with Neapope, White Cloud, and eight other leaders.

"[31] The doubt surrounding the work’s authenticity is more than merited as the words were dictated by Black Hawk, translated into English by LeClaire, and written into manuscript form by Patterson.

"Quasquawma, was chief of this tribe once, but being cheated out of the mineral country, as the Indians allege, he was denigrated from his rank and his son-in-law Taimah elected in his stead.

After Black Hawk led an aborted takeover of Fort Madison in the Spring of 1809, Quashquame worked to restore relations with the US Army the next day.

[36] Quashquame told Gen. William Clark during a meeting in 1810 or 1811: My father, I left my home to see my great-grandfather, the president of the United States, but as I cannot proceed to see him, I give you my hand as to himself.

Black Hawk thought this was an ideal arrangement: ... all the children and old men and women belonging to the warriors who had joined the British were left with them to provide for.

As Quashquame was eclipsed by his son-in-law Taimah as the Sauk chief favored by the U.S., his compromise position lost standing compared to Black Hawk's resistance.

When Caleb Atwater wrote about his visit to Quashquame in 1829, he depicted the leader as feeble, more interested in art and leisure than politics, but still advocating diplomacy over conflict.

He presented the noble spectacle of a warrior chief, conquered and disgraced with his tribe by his conquerors; but, resigned to his fate and covered with the scars of many battles, in the spirit of true heroism, breaking bread with and enjoying the hospitality of his destroyers.

[citation needed] In an 1838 address at Fort Madison (now Old Settlers Park, Iowa), in the year of his death, he said the following: It has pleased the Great Spirit that I am here today—I have eaten with my white friends.

Black Hawk's sons Nashashuk and Gamesett went to Governor Robert Lucas of Iowa Territory, who used his influence to bring the bones to security in his offices in Burlington.

[45] An alternative account is that Governor Lucas passed Black Hawk's bones to Enos Lowe, a Burlington physician, who was said to have left them to his partner, Dr. McLaurens.

Black Hawk's wife was known as As-she-we-qua[47] (died August 28, 1846),[48] or Singing Bird (her English name was Sarah Baker) with whom he had five children.

[54] The Wisconsin born African American spiritualist and trance medium Leafy Anderson claimed that Black Hawk was one of her major spirit guides.

[55][56][57] Special "Black Hawk services" are held to invoke his assistance, and busts or statues representing him are kept on home and church altars by his devotees.