African-American family structure

[3] From the initial involuntary migration of African Americans to the United States an ad hoc family structure, assembled based on enslaved people that lived in proximity to one another, and changed and adjusted as enslaved persons were sold, died prematurely or disconnected in some other manner, creating more emphasis on the extended family and non-biological connectedness of people as opposed to formalized titles and relatioships.

As a result, the evolution of African American family structure must be understood in distinct periods, each reflecting the impact of slavery, emancipation, and systemic racial oppression.

This approach resulted in significant demographic and social ramifications, including the prevalence of matrifocal family structures, enforced celibacy among men, early widowhood for women, and the absence of fathers in the lives of children.

The conditions of slavery and the enforced celibacy in the United States, where men struggled to find partners in predominantly male environments, have been associated with a rise in the prevalence of single-mother households.

[16] This historical context is essential for examining how African American families adapted, survived, and evolved over time in response to these external pressures.

[19] Data from U.S. census reports reveal that between 1880 and 1960, married households consisting of two-parent homes were the most widespread form of African-American family structures.

The typology includes the following categories: Billingsley identifies several substrata within African American families that reflect the diversity and complexity of their structures.

[13] E. Franklin Frazier has described the current African-American family structure as having two models, one in which the father is viewed as a patriarch and the sole breadwinner, and one where the mother takes on a matriarchal role in the place of a fragmented household.

[20] In 1997, McAdoo stated that African-American families are "frequently regarded as poor, fatherless, dependent of governmental assistance, and involved in producing a multitude of children outside of wedlock.

[49] Thomas, Krampe, and Newton relies on a 2002 survey that shows how the father's lack of presence has resulted in several negative effects on children ranging from education performance to teen pregnancy.

According to Brown, this lack of a second party income has resulted in the majority of African-American children raised in single mother households having a poor upbringing.

"[65] The mortality in this age group is accompanied by a significant number of illnesses in the pre- and post-natal care stages, along with the failure to place these children into a positive, progressive learning environment once they become toddlers.

[66] Jones, Zalot, Foster, Sterrett, and Chester executed a study examining the childrearing assistance given to young adults and African-American single mothers.

[67]: 673 In Jones research she also notes that 97% of single mothers aged 28–40 admitted that they rely on at least one extended family member for assistance in raising their children.

Some researchers theorize that the low economic statuses of the newly freed slaves in 1850 led to the current family structure for African Americans.

[69] Some researchers have hypothesized that these African traditions were modified by experiences during slavery, resulting in a current African-American family structure that relies more on extended kin networks.

"[71] There are several other factors which may have accelerated decline of the black family structure such as 1) The advancement of technology lessening the need for manual labor to more technical know-how labor; and 2) The women's rights movement in general opened up employment positions increasing competition, especially from white women, in many non-traditional areas which skilled blacks may have contributed to maintain their family structure in the midst of the rise of the cost of living.

[73] Fewer labor force opportunities and a decline in real earnings for black males since 1960 are also recognized as sources of increasing marital instability.

[75] In addition to social sanction, expanded access to legal institutions by poor communities, mainly brought about by the Neighborhood Legal Services Program (LSP) as part of the War on Poverty (1965), is seen as contributing, directly and indirectly, to changes in family structure flowing from the 1960s, in which marriage rates began to significantly decreased while divorces and nonmarital births increased.

[81] Incarceration has been associated with a higher risk of disease, increased likelihood of smoking cigarettes, and premature death, impacting these former inmates and their ability to be normalized in society.

[80] This further impacts social structure, as studies show that paternal incarceration may contribute to children's behavioral problems and lower performance in school.

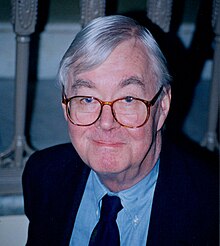

The Moynihan Report, written by Assistant Secretary of Labor, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, initiated the debate on whether the African-American family structure leads to negative outcomes, such as poverty, teenage pregnancy and gaps in education or whether the reverse is true and the African American family structure is a result of institutional discrimination, poverty and other segregation.

[83] Regardless of the causality, researchers have found a consistent relationship between the current African American family structure and poverty, education, and pregnancy.

In one study examining the effects of single-parent homes on parental stress and practices, the researchers found that family structure and marital status were not as big a factor as poverty and the experiences the mothers had while growing up.

Particularly relevant for families centered on black matriarchy, one theory posits that the reason children of female-headed households do worse in education is because of the economic insecurity that results because of single motherhood.

[98] Authors Angela Hattery and Earl Smith have proffered solutions to addressing the high rate of black children being born out of wedlock.

[99]: 285–315 Three of Hattery and Smith's solutions focus on parental support for children, equal access to education, and alternatives to incarceration for nonviolent offenders.

[99]: 306 For the past 400 years of America's life many African-Americans have been denied the proper education needed to provide for the traditional American family structure.

[99]: 308 Hattery suggests that the schools and education resources available to most African-Americans are under-equipped and unable provide their students with the knowledge needed to be college ready.

This conclusion is made from the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research report that stated only 23% of African-American students who graduated from public high school felt college-ready.