Hunger in the United States

Public interventions include changes to agricultural policy, the construction of supermarkets in underserved neighborhoods, investment in transportation infrastructure, and the development of community gardens.

In 2011, a report presented in the New York Times found that among 20 economies recognized as advanced by the International Monetary Fund and for which comparative rankings for food security were available, the U.S. was joint worst.

Urban areas by contrast have shown through countless studies that an increase in the African American population correlates to fewer supermarkets and the ones available require residents to travel a longer distance.

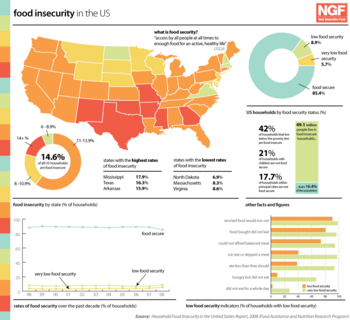

Food insecurity is highest in Alabama, Arkansas, Indiana, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, New Mexico, Ohio, Oklahoma, Texas, and West Virginia.

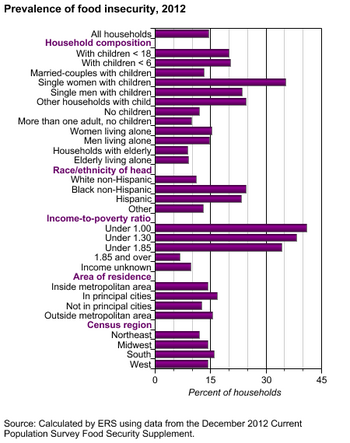

For households with young children, indicators had suggested food insecurity may have reached about 40%, close to four times the prevalence in 2018, or triple what was seen for the previous peak that occurred in 2008, during the Great Recession.

[38] Data from a large southwestern university show that 32% of college freshmen, who lived in residence halls, self-reported inconsistent access to food in the past month.

Studies conducted in California, Illinois, Texas, Los Angeles, Oregon, and Iowa have shown elevated rates of food insecurity among immigrant families and individuals.

Other signs could include: vitamin deficiency, osteocalcin, anemia, muscle tenderness, weakening of the muscular system, loss of sensation in extremities, heart failure, cracked lips, diarrhea and dementia.

Food insecure individuals, who live in low-income communities experience higher rates of chronic disease, leading to healthcare costs which create more financial hardships.

[87] Although income cannot be labeled as the sole cause of hunger, it plays a key role in determining if people possess the means to provide basic needs to themselves and their family.

[87] People who live in areas with higher unemployment rates and who have a minimal or very low amount of liquid assets are shown to be more likely to experience hunger or food insecurity.

[1] Furthermore, business owners and managers are often discouraged from establishing grocery stores in low-income neighborhoods due to reduced demand for low-skilled workers, low-wage competition from international markets, zoning laws, and inaccurate perceptions about these areas.

People with poor living conditions, less education, less money, and from disadvantaged neighborhoods may experience food insecurity and face less healthy eating patterns, which resulting in a higher level of diet-related health issues.

Due to the heavy subsidization of crops such as corn and soybeans, healthy foods such as fruits and vegetables are produced in lesser abundance and generally cost more than highly processed, packaged goods.

[105] Because "there is no popularly conceived, comprehensive plan in the U.S. with measurable benchmarks to assess the success or failures of the present approach [to hunger]," it is difficult for the US public to hold "government actors accountable to progressively improving food and nutrition status.

"[101] In 2014, the American Bar Association adopted a resolution urging the US government "to make the realization of a human right to adequate food a principal objective of U.S. domestic policy.

[111] In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic and economic volatility have spurred mass layoffs or hour reductions, specifically in the transportation, service, leisure, and hospitality industries and domestic workers.

[113][114][115] Persons of color are more likely to work ‘essential’ jobs, such as grocery store clerks, or in healthcare, thus they are at a higher risk of exposure for contracting the virus, which could lead to loss of hourly wages.

"[118][119] According to the United States Department of Agriculture in 2015, over 30% of households with children headed by a single mother were food insecure, and this number is expected to rise as a result of any economic downturn.

[124][15] As of 2012, the United States government spent about $50 billion annually on 10 programs, mostly administrated by the Center for Nutrition Policy and Promotion, which in total deliver food assistance to one in five Americans.

[3] The implementation of policies that reduce the subsidization of crops such as corn and soybeans and increase subsidies for the production of fresh fruits and vegetables would effectively provide low-income populations with greater access to affordable and healthy foods.

[3] This method is limited by the fact that the prices of animal-based products, oils, sugar, and related food items have dramatically decreased on the global scale in the past twenty to fifty years.

[3] According to the Nutritional Review Journal, a reduction or removal of subsidies for the production of these foods will not appreciably change their lower cost in comparison to healthier options such as fruits and vegetables.

[143] Similarly, Internal Revenue Code 170(e)(3) grants tax deductions to businesses in order to encourage them to donate healthy food items to nonprofit organizations that serve low-income populations.

As was the case in Europe, many influential Americans believed in classical liberalism and opposed federal intervention to help the hungry, as they thought it could encourage dependency and would disrupt the operation of the free market.

The 1870s saw the AICP and the American branch of the Charity Organization Society successfully lobby to end the practice where city official would hand out small sums of cash to the poor.

Despite this, there was no nationwide restrictions on private efforts to help the hungry, and civil society immediately began to provide alternative aid for the poor, establishing soup kitchens in U.S.

A second response to the "rediscovery" of hunger in the mid-to-late sixties, spurred by Joseph S. Clark's and Robert F. Kennedy's tour of the Mississippi Delta, was the extensive lobbying of politicians to improve welfare.

In the early 1980s, President Ronald Reagan's administration scaled back welfare provision, leading to a rapid rise in activity from grass roots hunger relief agencies.

[162] Demand for the services of emergency hunger relief agencies increased further in the late 1990s, after the "end of welfare as we know it" with President Clinton's Personal Responsibility and Work Opportunity Act.