Bliesbruck Baths

The bath elements were uncovered between 1987 and 1993 and are now part of the European Archaeological Park of Bliesbruck-Reinheim, housed in a museum pavilion designed to preserve the remains.

[F 1] The Bliesbruck-Reinheim was occupied as early as the protohistoric period and gained significance in the 5th century BC with a princely Celtic character.

In the eastern quarter, archaeologists have discovered several food cooking installations and a 750 m2 structure possibly used for the "meeting of a professional or religious association.

[F 1] The site was later occupied during the Middle Ages, with a Merovingian necropolis and a fortified house established in the baths in the 15th and 16th centuries.

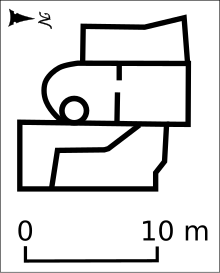

[E 3] Each wing measures approximately 4.9 m by 30 m. Along the east and south sides, there is a row of seven shops located next to the palestra, which is supported by a portico with wooden pillars.

[C 4] In the 2nd century, minor modifications were made, including the addition of latrines to the south of the central complex, supplied during the emptying of the frigidarium and by another drainage channel.

[C 7] The small entrance building was replaced by a larger structure, the caldarium was reconstructed, and the palaestra pool was filled in.

[E 10] The small building situated on the former palaestra was demolished, transforming the area into a service space with paved paths and a latrine exclusively designated for personnel.

[C 3] After the damages of the late 3rd century, a portion of the building was restored but no longer used for bathing;[C 3] the rooms were gradually left unheated.

[B 7] Materials, particularly lead, were salvaged, with individuals even dismantling walls to retrieve the pipes, leaving behind traces in the frigidarium's mortar.

[F 7] The site revealed artifacts from the medieval period found in the frigidarium, including pottery sherds,[B 13] fragments of horseshoes, iron objects, and a few silver coins.

[B 3] Additionally, a variety of decorative elements, including rings, beads, hairpins, and fibulae, were discovered, most of which belonged to women.

[F 8] Various items related to textile craftsmanship were also uncovered in the baths, although it is difficult to make precise conclusions about on-site activities.

[C 10] The museum space for the baths has been intentionally minimized to "maintain the emotional impact of the authentic excavated ruins."

[E 14] Archaeologists have discovered interior decor elements on a white background with colored bands and plant motifs, as well as garlands from the initial phase of the building's history.

[E 2] The building layout is linear, reminiscent of a style found in Pompeii,[C 7] with the monumental effect enhanced by two wings of shops that provide symmetry.

[B 3] This room may have served as a space for physical exercises, oil anointing,[C 13] or other care activities, as archaeologists have uncovered a variety of utensils used for these purposes.

[F 6] These boutiques are designed for artisanal or commercial purposes, serving as taverns and providing a barrier from street disturbances for users of the palaestra.

The boutiques have removable wooden panels for opening and closing, similar to those found in excavations of Pompeii and Herculaneum, where molds of such installations have been preserved.

The boiler, typically constructed of bronze or lead, has two reservoirs above a masonry mass where cold water is stored to regulate temperatures.

[E 10] In small towns, baths were not used simultaneously by men and women due to the lack of independent spaces, unlike larger thermal complexes.

[F 16] The baths of Bliesbruck are a key feature of "a complex with expanded social and economic functions," serving as the main building of the public center.

While baths in other vici are also recognized, their significance within settlements is often overlooked, except at Bliesbruck where their "integration into the social and economic space is well understood.

[E 25] The building's monumental nature suggests it may have been constructed through the euergetism of local notables, with its operation possibly supported by the system of liturgies.

While no epigraphic evidence has been found on the site to confirm this, a discovery at an important thermal establishment in Heerlen, where a decurion restored the complex after making a vow to Fortuna, supports this hypothesis.

[E 25] Sculpted deity remains found in the baths may have served as decorative elements or symbols of patronage, with some possibly being dedicated.

[F 17] Benefaction in Belgic Gaul, including among the Mediomatrici, is carried out by both local elites and communities, such as vici or pagi, organized under the authority of decurions.

The baths of Bliesbruck were constructed either by a prominent individual or by the community, possibly with the involvement of "one or more local notables" who held official positions.

[C 3] The baths are part of the installations that demonstrate the rapid spread of the Roman lifestyle, not only in major cities but also in small settlements like the vicus of Bliesbruck.

[E 2] The history of the thermal complex of Bliesbruck, with its various phases of expansion, testifies to the growing importance, over time, of heated non-bathing rooms.