Basilica

In Ancient Roman architecture, a basilica (Greek Basiliké) was a large public building with multiple functions that was typically built alongside the town's forum.

[2] After the construction of Cato the Elder's basilica, the term came to be applied to any large covered hall, whether it was used for domestic purposes, was a commercial space, a military structure, or religious building.

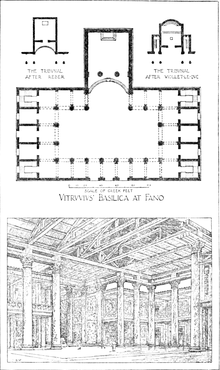

[3] These basilicas were rectangular, typically with central nave and aisles, usually with a slightly raised platform and an apse at each of the two ends, adorned with a statue perhaps of the emperor, while the entrances were from the long sides.

As early as the time of Augustus, a public basilica for transacting business had been part of any settlement that considered itself a city, used in the same way as the covered market houses of late medieval northern Europe, where the meeting room, for lack of urban space, was set above the arcades, however.

These basilicas were reception halls and grand spaces in which élite persons could impress guests and visitors, and could be attached to a large country villa or an urban domus.

[3] Long, rectangular basilicas with internal peristyle became a quintessential element of Roman urbanism, often forming the architectural background to the city forum and used for diverse purposes.

[6] Beginning with Cato in the early second century BC, politicians of the Roman Republic competed with one another by building basilicas bearing their names in the Forum Romanum, the centre of ancient Rome.

[3] Provinces in the west lacked this tradition, and the basilicas the Romans commissioned there were more typically Italian, with the central nave divided from the side-aisles by an internal colonnade in regular proportions.

[11] At Ephesus the basilica-stoa had two storeys and three aisles and extended the length of the civic agora's north side, complete with colossal statues of the emperor Augustus and his imperial family.

[3] To improve the quality of the Roman concrete used in the Basilica Ulpia, volcanic scoria from the Bay of Naples and Mount Vesuvius were imported which, though heavier, was stronger than the pumice available closer to Rome.

[19] The basilica was built together with a forum of enormous size and was contemporary with a great complex of public baths and a new aqueduct system running for 82 miles (132 km), then the longest in the Roman Empire.

[24] Traditional monumental civic amenities like gymnasia, palaestrae, and thermae were also falling into disuse, and became favoured sites for the construction of new churches, including basilicas.

[28] At Dion near Mount Olympus in Macedonia, now an Archaeological Park, the latter 5th century Cemetery Basilica, a small church, was replete with potsherds from all over the Mediterranean, evidencing extensive economic activity took place there.

[28][30] Likewise at Maroni Petrera on Cyprus, the amphorae unearthed by archaeologists in the 5th century basilica church had been imported from North Africa, Egypt, Palestine, and the Aegean basin, as well as from neighbouring Asia Minor.

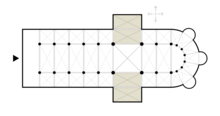

[3][32] Inside the basilica the central nave was accessed by five doors opening from an entrance hall on the eastern side and terminated in an apse at the western end.

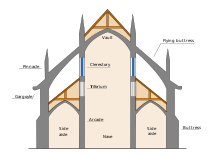

[34] A narthex (sometimes with an exonarthex) or vestibule could be added to the entrance, together with an atrium, and the interior might have transepts, a pastophorion, and galleries, but the basic scheme with clerestory windows and a wooden truss roof remained the most typical church type until the 6th century.

[9] According to the Liber Pontificalis, Constantine was also responsible for the rich interior decoration of the Lateran Baptistery constructed under Pope Sylvester I (r. 314–335), sited about 50 metres (160 ft).

[25] Above an originally 1st century AD villa and its later adjoining warehouse and Mithraeum, a large basilica church had been erected by 350, subsuming the earlier structures beneath it as a crypt.

[25] Similarly, at Santi Giovanni e Paolo al Celio, an entire ancient city block – a 2nd-century insula on the Caelian Hill – was buried beneath a 4th-century basilica.

[25] By 350 in Serdica (Sofia, Bulgaria), a monumental basilica – the Church of Saint Sophia – was erected, covering earlier structures including a Christian chapel, an oratory, and a cemetery dated to c.

[37] According to Augustine of Hippo, the dispute resulted in Ambrose organising an 'orthodox' sit-in at the basilica and arranged the miraculous invention and translation of martyrs, whose hidden remains had been revealed in a vision.

[37] During the sit-in, Augustine credits Ambrose with the introduction from the "eastern regions" of antiphonal chanting, to give heart to the orthodox congregation, though in fact music was likely part of Christian ritual since the time of the Pauline epistles.

[24] At Chalcedon, opposite Constantinople on the Bosporus, the relics of Euphemia – a supposed Christian martyr of the Diocletianic Persecution – were housed in a martyrium accompanied by a basilica.

[53] This monastery was the administrative centre of the Pachomian order where the monks would gather twice annually and whose library may have produced many surviving manuscripts of biblical, Gnostic, and other texts in Greek and Coptic.

[54] Generally, North African basilica churches' altars were in the nave and the main building medium was opus africanum of local stone, and spolia was infrequently used.

[56] At Nicopolis in Epirus, founded by Augustus to commemorate his victory at the Battle of Actium at the end of the Last war of the Roman Republic, four early Christian basilicas were built during Late Antiquity whose remains survive to the present.

[66] Qasr Serīj's construction may have been part of the policy of toleration that Khosrow and his successors had for Miaphysitism – a contrast with Justinian's persecution of heterodoxy within the Roman empire.

[66] This policy itself encouraged many tribes to favour the Persian cause, especially after the death in 569 of the Ghassanid Kingdom's Miaphysite king al-Harith ibn Jabalah (Latin: Flavius Arethas, Ancient Greek: Ἀρέθας) and the 584 suppression by the Romans of his successors' dynasty.

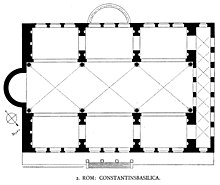

It is a long rectangle two storeys high, with ranks of arch-headed windows one above the other, without aisles (there was no mercantile exchange in this imperial basilica) and, at the far end beyond a huge arch, the apse in which Constantine held state.

The first great Imperially sponsored Christian basilica is that of St John Lateran, which was given to the Bishop of Rome by Constantine right before or around the Edict of Milan in 313 and was consecrated in the year 324.

Variations: Where the roofs have a low slope, the triforium gallery may have own windows or may be missing.