Blue Riband

The Blue Riband (/ˈrɪbənd/) is an unofficial accolade given to the passenger liner crossing the Atlantic Ocean in regular service with the record highest average speed.

[4][Note 1] Of the 35 Atlantic liners to hold the Blue Riband, 25 were British, followed by five German, three American, and one each from Italy and France.

Thirteen were Cunarders (plus Queen Mary of Cunard White Star), five White Star liners, with four owned by Norddeutscher Lloyd, two by Collins, two by Inman, two by Guion, and one each by British American, Great Western, Hamburg-America, the Italian Line, Compagnie Générale Transatlantique and finally the United States Lines.

The trophy continues to be awarded, though many people believe United States remains as the holder of the Blue Riband,[7] because no subsequent record-breaker was in Atlantic passenger service.

[8] Over the next three centuries, countless vessels (merchant ships and warships, fast and slow, in peace and war) crossed back and forth over the North Atlantic, all subject to the vagaries of wind and weather.

It was the advent of the steamship, with its independence from wind power, which offered the possibility of regular, scheduled Atlantic crossings, in periods of two to three weeks, that opened a new era of transatlantic travel and competition.

[9] The term "Blue Riband of the Atlantic" did not come into use until the 1890s, and the history of the trans-Atlantic competition, which was compiled retrospectively, was regarded as starting with the crossings by the steamships Sirius and Great Western in 1838.

[12] The idea of building a line of transatlantic steamships was mooted in 1832 by Junius Smith, an American lawyer turned London merchant.

[2] Smith, who is often considered the Father of the Atlantic Liner, formed the British and American Steam Navigation Company to operate a London-New York service.

By 1846, Cunard was the only original steamship line that survived, largely because of its subsidy from the British Admiralty to carry the mails[3] and its emphasis on safety.

[3] The next year, Cunard put further pressure on Collins by commissioning its first iron-hulled paddler, the Persia, which set a new record with a 9-day, 16-hour Liverpool–New York voyage at 13.11 knots (24.28 km/h).

[3] Cunard emerged as the leading carrier of first-class passengers and in 1862 commissioned the Scotia, the last paddle steamer to set a record with a Queenstown-New York voyage at 14.46 knots (26.78 km/h).

Scotia was the final significant paddler ordered for the Atlantic because under the terms of Cunard's mail contract with the Admiralty, it was still required to supply paddle steamers when needed for military service.

[17] The new White Star record-breakers were especially economical because of their use of compound engines, but their high ratio of length to beam (10:1 compared to the previous norm of 8:1) increased vibration.

[3] When Cunard rejected his proposal, Pearce offered his idea to the Guion Line, a firm primarily engaged in the steerage trade.

[1] The Inman line fell on hard times after their intended record-breaker, City of Rome failed to meet expectations and was returned to her builders in 1882.

White Star, which had not built an express liner since the Germanic of 1875, commissioned the record-breaker, Teutonic of 1889 and Majestic of 1890 after receiving a subsidy from the Admiralty to make the pair available as merchant cruisers in the event of hostilities.

[1] Rather than match the new German speedsters, White Star decided to drop out of the competition and commission the four large Celtic-class luxury liners of more moderate speed.

After its bad experience with the Deutschland, Hamburg America also dropped out of the race and commissioned large luxury liners based on the Celtic.

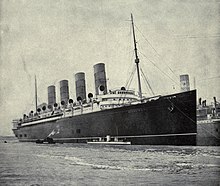

British prestige was at stake, and the Government provided Cunard with an annual subsidy of £150,000 plus a low-interest loan of £2.5 million to pay for the construction of the two superliners, Lusitania and Mauretania, under the condition that they be available for conversion to armed cruisers when needed by the navy.

[17] However, these ships paid a price for speed and lacked many of the amenities found in the new White Star and Hamburg American luxury liners.

[5] There is a persistent rumor that RMS Titanic was attempting to win the Blue Riband and that such effort resulted in excessive speed and collision with the iceberg.

By this time, improvements in turbine technology and hull form, along with the use of fuel oil instead of coal, made it possible to build more civilised record breakers.

[6] Other rule changes further complicated the situation, and eventually the trophy was awarded to just three Blue Riband holders; Rex, in 1935, Normandie in 1936, and United States in 1952.

[1] With the success of United States in 1952, with average speed of 35.59 knots (65.91 km/h), and Cunard's decision not to challenge the new record, the Blue Riband contest again subsided.

In 1992, the Virgin Atlantic Challenge was won by the Aga Khan's Destriero, crossing in 58 hours 34 minutes and averaging 53.09 knots.

Meanwhile, Incat, builders of fast catamaran ferries, and therefore indisputably commercial vessels, decided to make an attempt to win the Hales Trophy, the record still held by United States.

With the end of the express liners era, the Blue Riband has become an item of largely historical interest, with some authors regarding the United States as the last holder of the accolade.

Therefore, most lists feature Sirius, in her race with Great Western in 1838, as the first record-holder, although her crossing was not as fast as some sail packet ships of the period.

Since then, C. R. Vernon Gibbs (1952),[3] and Noel Bonsor (1975)[4] added to the body of knowledge, with additional detail about the German ships provided by Arnold Kludas.