Kingdom of Bohemia

Although some former rulers of Bohemia had enjoyed a non-hereditary royal title during the 11th and 12th centuries (Vratislaus II, Vladislaus II), the kingdom was formally established (by elevating Duchy of Bohemia) in 1198 by Přemysl Ottokar I, who had his status acknowledged by Philip of Swabia, elected King of the Romans, in return for his support against the rival Emperor Otto IV.

Under these terms, the Czech king was to be exempt from all future obligations to the Holy Roman Empire except for participation in the imperial councils.

Wenceslaus I's sister Agnes, later canonized, refused to marry the Holy Roman Emperor and instead devoted her life to spiritual works.

German Emperor Frederick II's preoccupation with Mediterranean affairs and the dynastic struggles known as the Great Interregnum (1254–73) weakened imperial authority in Central Europe, thus providing opportunities for Přemyslid assertiveness.

He campaigned as far as Prussia, where he defeated the pagan natives and in 1256, founded a city he named Královec in Czech, which later became Königsberg (now Kaliningrad).

In 1260, Ottokar defeated Béla IV, king of Hungary in the Battle of Kressenbrunn near the Morava river, where more than 200,000 men clashed.

All of Ottokar's German possessions were lost in 1276, and in 1278 he was abandoned by part of the Czech nobility and died in the Battle on the Marchfeld against Rudolf.

In 1306, the Přemyslid line died out and, after a series of dynastic wars, John, Count of Luxembourg, was elected Bohemian king.

In 1344 he elevated the bishopric of Prague, making it an archbishopric and freeing it from the jurisdiction of Mainz, and the archbishop was given the right to crown Bohemian kings.

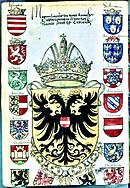

The next year he issued the Golden Bull of 1356, defining and codifying the process of election to the Imperial throne, with the Bohemian king among the seven electors.

Charles intended to make Prague into an international center of learning, and the university was divided into Czech, Polish, Saxon, and Bavarian "nations", each with one controlling vote.

The Hussites defeated four crusades from the Holy Roman Empire, and the movement is viewed by many as a part of the (worldwide) Protestant Reformation.

Hussitism began during the long reign of Wenceslaus IV (1378–1419), a period of papal schism and concomitant anarchy in the Holy Roman Empire.

A reformist preacher, Hus espoused the anti-papal and anti-hierarchical teachings of John Wycliffe of England, often referred to as the "Morning Star of the Reformation".

He advocated the Wycliffe doctrine of clerical purity and poverty, and insisted on the laity receiving communion under both kinds, bread and wine.

His favoring of Germans in appointments to councillor and other administrative positions had aroused the nationalist sentiments of the Czech nobility and rallied them to Hus' defense.

Imprisoned when he arrived, he was allowed no legal advocate for his defense; the council condemned him as a heretic and relinquished him to an imperial secular court, which decreed he be burned at the stake in 1415.

Sigismund, the pro-papal king of Hungary and successor to the Bohemian throne after the death of Wenceslas in 1419, failed repeatedly to gain control of the kingdom despite aid by Hungarian and German armies.

Žižka led armies to storm castles, monasteries, churches, and villages, expelling the Catholic clergy, expropriating ecclesiastical lands, or accepting conversions.

The Compacts of Basel accepted the basic tenets of Hussitism expressed in the Four Articles of Prague: communion under both kinds; free preaching of the Gospels; expropriation of church land; and exposure and punishment of public sinners.

George installed another Utraquist, John of Rokycany, as archbishop of Prague and succeeded in uniting the more radical Taborites with the Czech Reformed Church.

The Bohemian War (1468-1478) pitted Bohemia against Matthias Corvinus and Frederick III of Habsburg, and the Hungarian forces occupied most of Moravia.

In 1526, Vladislav's son, King Louis, was decisively defeated by the Ottoman Turks at the Battle of Mohács and subsequently died.

As a result, the Turks conquered part of the Kingdom of Hungary, and the rest (mainly present-day Slovakia territory) came under Habsburg rule under the terms of King Louis' marriage contract.

The Bohemian estates in 1526 elected Austrian Archduke Ferdinand, younger brother of Emperor Charles V, to succeed Louis as king of Bohemia.

From 1599 to 1711, Moravia (a Land of the Bohemian Crown) was frequently subjected to raids by the Ottoman Empire and its vassals (especially the Tatars and Transylvania).

[13] The incorporation of Bohemia into the Habsburg monarchy against the resistance of the local Protestant nobility sparked the 1618 Defenestration of Prague, the brief reign of the Winter King, and the Thirty Years' War.

In 1756 Prussian King Frederick II faced an enemy coalition led by Austria, when Maria Theresa was preparing for war with Prussia to reclaim Silesia.

These included the following in different time periods: According to Johann Gottfried Sommer Bohemia was divided into 16 district units between 1833 and 1849: In 1849 the number of Kreise/Kraje was reduced to seven.

These Kraje/Kreise were subdivided into between twelve and 20 Bezirke (207 in total, plus the capital city of Prague); these acted merely as administrative units of the Kraje/Kreise rather than taking on powers of their own.