Bohrium

Chemistry experiments have confirmed that bohrium behaves as the heavier homologue to rhenium in group 7.

The chemical properties of bohrium are characterized only partly, but they compare well with the chemistry of the other group 7 elements.

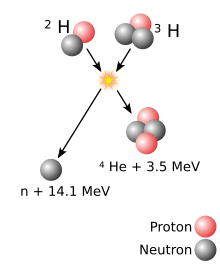

[d] This fusion may occur as a result of the quantum effect in which nuclei can tunnel through electrostatic repulsion.

[22] The definition by the IUPAC/IUPAP Joint Working Party (JWP) states that a chemical element can only be recognized as discovered if a nucleus of it has not decayed within 10−14 seconds.

This value was chosen as an estimate of how long it takes a nucleus to acquire electrons and thus display its chemical properties.

However, its range is very short; as nuclei become larger, its influence on the outermost nucleons (protons and neutrons) weakens.

[g] Almost all alpha emitters have over 210 nucleons,[35] and the lightest nuclide primarily undergoing spontaneous fission has 238.

[j] Spontaneous fission, however, produces various nuclei as products, so the original nuclide cannot be determined from its daughters.

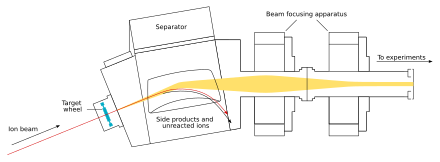

Evidence of bohrium was first reported in 1976 by a Soviet research team led by Yuri Oganessian, in which targets of bismuth-209 and lead-208 were bombarded with accelerated nuclei of chromium-54 and manganese-55, respectively.

Since the ratio of the intensities of these two activities was constant throughout the experiment, it was proposed that the first was from the isotope bohrium-261 and that the second was from its daughter dubnium-257.

The IUPAC/IUPAP Transfermium Working Group (TWG) concluded that while dubnium-258 was probably seen in this experiment, the evidence for the production of its parent bohrium-262 was not convincing enough.

[55] In 1981, a German research team led by Peter Armbruster and Gottfried Münzenberg at the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research (GSI Helmholtzzentrum für Schwerionenforschung) in Darmstadt bombarded a target of bismuth-209 with accelerated nuclei of chromium-54 to produce 5 atoms of the isotope bohrium-262:[56] This discovery was further substantiated by their detailed measurements of the alpha decay chain of the produced bohrium atoms to previously known isotopes of fermium and californium.

The IUPAC/IUPAP Transfermium Working Group (TWG) recognised the GSI collaboration as official discoverers in their 1992 report.

[55] In September 1992, the German group suggested the name nielsbohrium with symbol Ns to honor the Danish physicist Niels Bohr.

The Soviet scientists at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in Dubna, Russia had suggested this name be given to element 105 (which was finally called dubnium) and the German team wished to recognise both Bohr and the fact that the Dubna team had been the first to propose the cold fusion reaction, and simultaneously help to solve the controversial problem of the naming of element 105.

Several radioactive isotopes have been synthesized in the laboratory, either by fusing two atoms or by observing the decay of heavier elements.

[71] The higher +7 oxidation state is more likely to exist in oxyanions, such as perbohrate, BhO−4, analogous to the lighter permanganate, pertechnetate, and perrhenate.

[72] Since the oxychlorides are asymmetrical, and they should have increasingly large dipole moments going down the group, they should become less volatile in the order TcO3Cl > ReO3Cl > BhO3Cl: this was experimentally confirmed in 2000 by measuring the enthalpies of adsorption of these three compounds.

[4] Bohrium is expected to be a solid under normal conditions and assume a hexagonal close-packed crystal structure (c/a = 1.62), similar to its lighter congener rhenium.

[73] In 2000, it was confirmed that although relativistic effects are important, bohrium behaves like a typical group 7 element.

[4] The longer-lived heavy isotopes of bohrium, produced as the daughters of heavier elements, offer advantages for future radiochemical experiments.