Bokator

[4] Oral tradition indicates that Bokator (or an early form thereof) was the close-quarter combat system used by the ancient Cambodian armies before the founding of Angkor.

According to the origin myth, a lion was attacking a village when a warrior, armed with only a knife, defeated the animal bare-handed, killing it with a single knee strike.

The martial art is believed to trace its origin back to the 1st century AD,[3][9] a time when early Khmer people, living amidst the wilderness, emulated the movements of animals for survival, resulting in the animal-inspired techniques found in Bokator.

[11] Further evidence of martial traditions can be found in a 9th-century inscription from Thnal Baray (inscription K.282C) which depicts King Yasovarman I as a skilled wrestler: In the exercise of wrestling, he would swiftly overcome ten very strong wrestlers and cast them to the ground in a heap by the thousand thrusts of his arms, as did the son of Kritavarya in combat for the one who had ten faces.

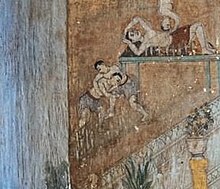

[13] Two imposing statues of wrestlers commissioned by King Jayavarman IV were discovered in Koh Ker and are estimated to date back to around 930 CE.

[23] In the 1800s, King Norodom used to hold and watch traditional martial arts fights within the royal palace and surrounded exclusively by his court.

Stick fighting was practiced with respect, order and discipline, captivating crowds as engaged men competed in front of their fiancé.

The wrestlers engaged in playful preliminaries: the Cham initiated by humorously examining the Cambodian's muscles, prompting the Khmer to retaliate by mimicking a trap around his wrists.

Both wrestlers played along cheerfully before commencing the bout, earning admiration and encouragement from men while drawing cries from concerned women.

[27] Boxing, stick-fighting, and wrestling, which are core components of Bokator, were described by French records in 1905 as among the favourite pastimes of Khmer people.

[28] The 1907 edition of the International Review of Sociology noticed the customary inclusion of martial arts tournaments within major celebrations, often featuring matches between Khmer and Cham champions.

[30] In response, the French colonial administration banned in 1920 Buddhist monks from instructing and participating in Khmer martial arts, aiming to prevent their potential contribution to social upheaval.

In April 1930, King Sisowath Monivong invited Resident Superior Fernand Marie Joseph Antoine Lavit to witness traditional martial arts inside the Royal Palace as part of the Khmer New Year celebrations.

Preceding the Second World War, Phnom Penh hosted diverse sporting events, including Khmer martial arts competitions.

[3] At the time of the Pol Pot regime (1975–1979) those who practiced traditional arts were either systematically exterminated by the Khmer Rouge, fled as refugees or stopped teaching and hid.

Once in America he started teaching hapkido at a local YMCA in Houston, Texas and later moved to Long Beach, California.

[1][34] In 2001, San Kim Sean moved back to Phnom Penh and, after getting permission from the new king, began teaching Bokator to local youth.

That same year in the hopes of bringing all of the remaining living masters together he began traveling the country seeking out Bokator lok kru, or instructors, who had survived the regime.

Dedicated grandmasters, including Ith Pen, Sen Sam Ath, San Kim Sean, Ros Serei, Am Yom, Suong Neng, Ponh Keun, Voeng Sophal, Ke Sam On, Kim Chiev, Chet Ay, and Kao Kob, work tirelessly to preserve and pass on this tradition.

[9] Tournaments occur at regional and national levels, sometimes with coordination by the Cambodia Kunbokator Federation (CKBF) and active participation from the masters.

[40][41][42] Before any fights, Bokator athletes pay tribute to their master by doing a ritual dance, called Tvay Bangkum Romleuk Kun Kru (Khmer: ថ្វាយបង្គំរម្លឹកគុណគ្រូ, lit.

A krama (scarf) is folded around their waist and blue and red silk cords called, sangvar day are tied around the combatants head and biceps.

This practice was documented by the French newspaper Le Saïgon sportif in 1933 and is said to enable fighters to inflict severe injuries with a punch.

They obediently follow their master's lead, who assumes dual roles as an instructor and a guardian, providing sustenance and attending to their well-being.

Classes usually end with meditation and breathing exercises meant to help blood flow, blending spiritual and physical aspects.

[2] Bokator exhibits slight regional variations, encompassing differences in physical techniques, tools, terminology, and favored skills.

[2] Bokator techniques make use of a wide range of body parts and weapons, including hands, elbows, knees, feet, sticks, swords, and spears.

Targets for the push kick range from below the belt to the chest and even up to the face, each offering different levels of impact and potential damage.

Once the kick is caught, the practitioner follows up by using their elbow to strike the opponent's thigh, targeting the muscle to inflict pain and disrupt their attack.

[51] Beyond martial arts, Bokator finds artistic applications in Chhay Yam, a Khmer traditional dance, as well as Khmer-style theatrical performances such as Lakhon Bassac.