Mexican cuisine

Mexican cuisine ingredients and methods begin with the first agricultural communities such as the Olmec and Maya who domesticated maize, created the standard process of nixtamalization, and established their foodways.

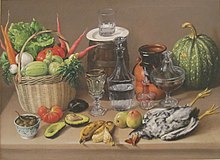

Today's food staples native to the land include corn (maize), turkey, beans, squash, amaranth, chia, avocados, tomatoes, tomatillos, cacao, vanilla, agave, spirulina, sweet potato, cactus, and chili pepper.

After the Spanish Conquest of the Aztec empire and the rest of Mesoamerica, Spaniards introduced a number of other foods, the most important of which were meats from domesticated animals (beef, pork, chicken, goat, and sheep), dairy products (especially cheese and milk), rice, sugar, olive oil and various fruits and vegetables.

Tropical fruits, many of which are indigenous to the Americas, such as guava, prickly pear, sapote, mangoes, bananas, pineapple and cherimoya (custard apple) are popular, especially in the center and south of the country.

Entemophagy or insect-eating is becoming increasingly popular outside of poor and rural areas for its unique flavors, sustainability, and connection to pre-Hispanic heritage.

Tortillas are made of maize in most of the country, but other regional versions exist, such as wheat in the north or plantain, yuca and wild greens in Oaxaca.

Together with Mesoamerica, Spain is the second basis of Mexican cuisine, contributing in two fundamental ways: Firstly, they brought with them old world staples and ingredients which did not exist in the Americas such as sugar, wheat, rice, onions, garlic, limes, cooking oil, dairy products, pork, beef and many others.

[25] Mexican cuisine is elaborate and often tied to symbolism and festivals, which is one reason it was named as an example of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity by UNESCO.

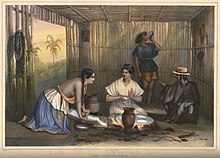

Before industrialization, traditional women spent several hours a day boiling dried corn then grinding it on a metate to make the dough for tortillas, cooking them one-by-one on a comal griddle.

[32][34] Mole is served at Christmas, Easter, Day of the Dead and at birthdays, baptisms, weddings and funerals, and tends to be eaten only for special occasions because it is such a complex and time-consuming dish.

This may have been because of economic crises at that time, allowing for the substitution of these cheaper foods, or the fact that they can be bought ready-made or may already be made as part of the family business.

[40] One attraction of street food in Mexico is the satisfaction of hunger or craving without all the social and emotional connotation of eating at home, although longtime customers can have something of a friendship/familial relationship with a chosen vendor.

They are served in a bolillo-style bun, typically topped by a combination of pinto beans, diced tomatoes, onions and jalapeño peppers, and other condiments.

[46] Besides food, street vendors also sell various kinds of drinks (including aguas frescas, tejuino, and tepache) and treats (such as bionicos, tostilocos, and raspados).

Around 7000 BCE, the indigenous peoples of Mexico and Central America hunted game and gathered plants, including wild chili peppers.

Other protein sources included amaranth, domesticated turkey, insects such as grasshoppers, beetles and ant larvae, iguanas, and turtle eggs on the coastlines.

[16] According to Bernardino de Sahagún, the Nahua peoples of central Mexico ate corn, beans, turkey, fish, small game, insects and a wide variety of fruits, vegetables, pulses, seeds, tubers, wild mushrooms, plants and herbs that they collected or cultivated.

[52] European style wheat bread was initially met unfavorably with Moctezuma's emissaries who reportedly described it as tasting of "dried maize stalks".

[51] Natives continued to be reliant on maize; it was less expensive than the wheat favored by European settlers, it was easier to cultivate and produced higher yields.

According to de Bergamo's account neither coffee nor wine are consumed, and evening meals ended with a small portion of beans in a thick soup instead, "served to set the stage for drinking water".

In Mexico, many professional chefs are trained in French or international cuisine, but the use of Mexican staples and flavors is still favored, including the simple foods of traditional markets.

It was created by a group of women chefs and other culinary experts as a reaction to the fear of traditions being lost with the increasing introduction of foreign techniques and foods.

[70] Another beverage (which can be served hot or cold) typical from this region is Tascalate, which is made of powdered maize, cocoa beans, achiote (annatto), chilies, pine nuts and cinnamon.

Popular foods in the city include barbacoa (a specialty of the central highlands), birria (from western Mexico), cabrito (from the north), carnitas (originally from Michoacán), mole sauces (from Puebla and central Mexico), tacos with many different fillings, and large sub-like sandwiches called tortas, usually served at specialized shops called 'Torterías'.

These large tortillas allowed for the creation of burritos in the border city of Ciudad Juárez, which eventually gained popularity in the Southwest United States.

Later in the colonial period, Oaxaca lost its position as a major food supplier and the area's cooking returned to a more indigenous style, keeping only a small number of foodstuffs, such as chicken and pork.

Oaxaca's regional chile peppers include pasilla oaxaqueña (red, hot and smoky), along with amarillos (yellow), chilhuacles, chilcostles and costeños.

[93] Other dishes include conch fillet (usually served raw, just marinated in lime juice), coconut flavored shrimp and lagoon snails.

[97] Traditionally, some dishes are served as entrées, such as the brazo de reina (a type of tamale made from chaya) and papadzules (egg tacos seasoned in a pumpkin seed gravy).

[106] Another remarkable moment for Mexican cuisine history in the U.S. comes from Houston Texas' Irma Galvan, whose restaurant was recognized and named an 'American classic' by the James Beard Foundation in 2008.